Putting Salmon on the Map

Columbia River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Columbia River Basin

Paula Burgess

Dir, Pacific Northwest Programs, Wild Salmon Center Former Oregon Natural Resource Advisor to the Governor

Sasha Twelker

Cartographer, Wild Salmon Center

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director and Photographer

Bonnie Muench

Photographer, Artist & Book Designer

Portland’s Wild Salmon Center has a dynamic approach to protecting North Pacific salmon from Japan, Russia, Kamchatka, Korea, Alaska and Canada down to the US Pacific Northwest. This international concept of salmon-focused programs and activities would include the many Pacific salmon species in Alaska, British Columbia and the Lower 48 states. Conservation of these migratory fish would involve the supporting many cultures in their man migratory regions and protecting those watershed ecosystems.

Sasha’s cartography illustrates varied ranges of habitat and migratory paths that define the complex salmon story. Meeting Paula and Sasha and perusing their maps underlined how our NWNL expedition was so clearly shaped by the presence of salmon in the Columbia River Basin.

After our meeting, Sasha created and sent NWNL a Multi-Species Index & US Map of Columbia River Basin Salmon highlighting salmon species in the Columbia River Basin. Links in Sasha’s map show locales and ratings of salmon species so dependent on conservation of their habitat.

VARIED STEWARDSHIP APPROACHES

WILD SALMON CENTER’S APPROACH

PURPOSE OF MAPPING SALMON

SALMON SPECIES: FROM CHINOOK to COHO

COHO SALMON on the Map

SOCKEYE SALMON on the MAP

GLOBAL CONSERVATION CONTROVERSIES

Wild Salmon Center has identified the important “seed sources” for salmon that are not yet an endangered species. This is a completely different approach from trying to get populations in the worst shape off the Endangered Species List…. [With our approach] if a species becomes extinct, we can repopulate that river and allow those fish to replenish themselves naturally. -- Paula Burgess

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

NWNL Paula, please start by sharing your background.

PAULA BURGESS I grew up in Washington State, moved to Alaska after college, lived in California and now in Oregon. The temperate rainforest is my home. I’ve never lived outside the temperate rainforest!

NWNL How did you end up working with Wild Salmon?

PAULA BURGESS I spent 30 years in government working at borough (i.e., county), state and federal levels. After all those years of working on salmon recovery, I felt that government can’t solve this problem.

Government is a part of the solution; but these fish are so complex. They go hundreds of miles to the headwaters; and then all the way back down to the ocean – the trip that you’ve just taken. They then go hundreds of miles out to sea. They’re so complex. Everyone along their migratory routes shares a piece of their recovery – and government can’t lead that effort.

I left government after working for federal and state agencies, the BLM, the Forest Service and the state of Oregon. For 5 years, I was Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber’s Natural Resource Advisor. He is an inspiring and awesome man, a river rafter, and a real leader when it comes to rivers. In his administration, we developed the West’s first recovery plan for salmon since the federal government hadn’t yet developed one. I couldn’t get one through. So, we developed one for Oregon’s salmon species. But even with that, we still couldn’t influence all the many levels needed for salmon recovery.

NWNL What drew you to the Wild Salmon Center?

PAULA BURGESS Wild Salmon Center looks at the whole range of North Pacific salmon, from Japan, Russia, Korea, Kamchatka, Alaska, Canada down to the Pacific Northwest and the Lower 48 States. Within this broad Northern Pacific Basin, we’ve identified those places that are strongholds for salmon – where salmon are thriving, in good shape, wild, and biologically still very diverse, but not hatchery populations.

Wild Salmon Center has identified the important “seed sources” for salmon that are not yet an endangered species. This is a completely different approach from trying to get populations in the worst shape off the Endangered Species List. All of that’s good, and this effort can weave in with and support that approach. But in case we’re not able to save all the species we need to save, we can be working on an insurance policy to protect the best of what’s left. Thus, if a species becomes extinct, we can repopulate that river and allow those fish to replenish themselves naturally.

The Klamath River Basin is a great example of a population of Spring Chinook in its Salmon River. There are only 100 of these Spring Chinook left. They’re not yet listed as Endangered Species because Spring and Fall Chinook are categorized together as one species – even though they have distinct timing for their runs. The Fall Chinook populations are in good shape, but there are only 100 Spring Chinook left on the entire planet. If this population blanks out, there’ll be no Spring Chinook left anywhere.

There’s a similar issue with Coho Salmon in the Columbia River Basin. There are only 2 or 3 Coho populations that are in good condition. The rest have been extricated throughout the Columbia Basin. If we don’t take good care of those few populations, we will lose that species as well. So, we try to focus on the species that are strategically very important and those geographical areas that are still strongholds.

It is that argument that caused me to give up a good federal salary and work for this small non-profit. Now I want to see if I can get all the people I’ve worked with in government to shift their focus – or at least spend some time developing this insurance policy. This insurance policy is to make sure we protect salmonid strongholds and the seed sources. If we can’t save them all – and we can’t – we can at least save the main species so that they can repopulate at some point when humans are no longer here.

Humans are just a temporary species on earth. We tend to think of ourselves as invincible, but we’re not. It’s just a matter of time till we go extinct. Homo sapiens went extinct. Neanderthals went extinct. It’s just a matter of time for Homo sapiens sapiens. The question is that, will we last 200 million years like the dinosaurs did? Or will we be gone in 1.5, 1.7 … million years. So far, we have been here for only a very short horizon in geologic time. Given the way we’re changing the face of the planet, I wouldn’t give us a very long trajectory.

NWNL Back to the present, I assume you are combining your background working with state and federal level officials with now working with Tribal Nations as well?

PAULA BURGESS Yes, in addressing North America’s wide range of anadromous salmon in North America, Wild Salmon Center is working with all people concerned about protecting these salmon strongholds. That is how we will recover and allow these species to thrive.

NWNL Sasha you are the cartographer for Wild Salmon Center?

SASHA TWELKER Yes, my maps support the Wild Salmon Center stronghold strategy. I use red dots to represent the 96 rivers that represent 60% of the total remaining wild salmon abundance across the North Pacific. To restore salmon abundance back up to where it could be, we must protect these populations and seed sources.

NWNL You are covering the Pacific salmon range that crosses that ocean and spans from the western coast of North America up through Alaska to Russia and Japan?

SASHA TWELKER Yes. Across the Pacific, I use a range of dark-to-light colors, with lighter colors representing where salmon generally reside during their ocean life,

PAULA BURGESS So, dark and light combined shows the range of North Pacific salmons. It is an impressive web, covering thousands of miles at sea and hundreds of miles up rivers.

NWNL I know there are many salmon species, but is there a general average for how far an individual salmon may travel out into the Pacific?

PAULA BURGESS Oh, they travel at least 1,000 miles out into the ocean. The Aleutian Islands themselves are about 1,000 miles long. Columbia River fish turning north go up through the Gulf of Alaska and can swim all the way over to Kamchatka, where they may be caught by Russian fisherman in Russian nets. We can radio tag them all the way across. We don’t know the exact extent, but it’s clear that they can go at least 1,000 miles.

NWNL How long does it take for salmon to swim from the mouth of the Columbia River to Russia’s side of this basin, which you say is within the range of salmon?

PAULA BURGESS I don’t know. We have Chinook salmon that go out to the ocean, spend 3 years there, and then come back. Some species stay out longer. They swim continually, whether in circles in the same area or continuing further to look for food. They follow currents to find food, and then they push back against currents.

NWNL Sasha, what aspects do you include on the maps you’ve created?

SASHA TWELKER We have a map of nearshore currents identifying each eco-region. Within each, we try to identify from 2 to 4 of the most important strongholds for salmon to make sure we protect those that have adapted to warm water – for example, in California and Japan. We’ve also identified their inland presence in the northern part of Columbia Basin headwaters – such as very warm areas in Idaho and some of the dryer areas. Fish adapted to warm water can be very important for studying the future of salmonids, both salmon and steelhead, and for learning how they evolve. Perhaps they change gradually; perhaps each fish adapts to warm water; or perhaps the species gradually moves north. We want to be sure that we keep all their identities as we preserve species populations– those adapted to warm water, as well as those that do well in cold water. Given climate change, this becomes very important.

For the first time, in northern Canada’s McKenzie River and north of Alaska, they have found all five major North American species of salmon and steelhead. In the past, there had only been incidental sightings of one species there. Now, with today’s warming trends, all five are represented as fish move north to find cold water. We expect new areas will become salmon strongholds in the future. But for now, our salmon strongholds are further south.

Our Pacific Salmon Conservation Assessment database gives scores based on diversity, abundance and threats that are overlaid and made into a score, with 5 or 6 being the highest scores. The scores are percentage-based and point out trends such as salmon are declining in some places, and also moving north.

NWNL How do you explain that new migratory pattern?

SASHA TWELKER The reason is increasingly warm waters. Some fish are adapting in lower reaches and some populations up in Idaho’s Columbia River are doing very well – better than I believe they used.

But, generally, salmon strongholds are still up in the North Country and moving north, up to Canada’s McKenzie River. The northward range is moving, but we haven’t accessed or shown these new northern areas. Our next adventure is to plot those northern ranges.

BONNIE MUENCH Very few people there, and so very few threats, hopefully. But also, there is very little data when people aren’t there.

NWNL Thankfully for No Water No Life, your maps show the strength of all salmon species’ populations within the Columbia River Basin.

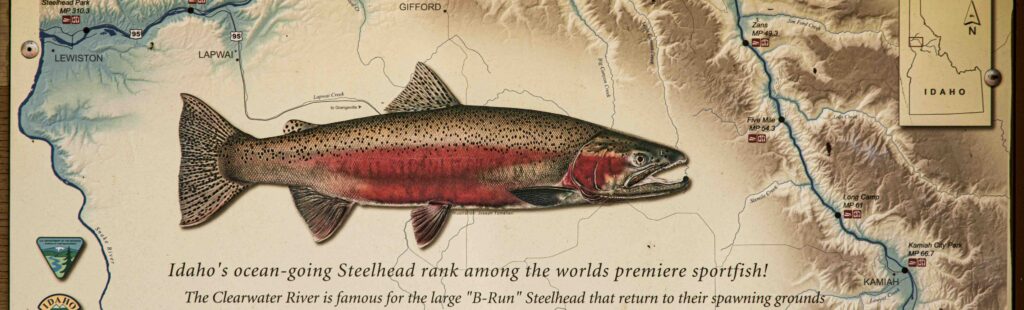

SASHA TWELKER Yes, we’ve studied the populations of Chinook, Sockeye, Coho, Chum and Steelhead and Pinks. As you know, the Columbia River Basin continues up to Canada, but we don’t have Canadian data. We do have all the US populations and indicate the viability of their productivity with different colors. While the lowest score is a 4 or 5, which applies to Steelhead, the highest possible scores given is 6 or 7.

The darkest blue on the map is in the Clackamas [southeast of Portland], most specifically Eagle Creek, because it has 4 of the 5 species and each rated very highly.

NWNL Does information on this map this relate to the impacts of dams?

PAULA BURGESS There are hundreds of dams in the Columbia system – many on tributaries and 13 major main stem dams. With each successive dam, fish have problems both getting up and juveniles have problems getting down. Most dams now have fish passage; but several don’t, including the Grand Coulee, Hell’s Canyon and the 4 Lower Snake River Dams.

SASHA TWELKER The Deschutes also has an impassable dam so there no salmon upriver of that – although there used to be amazing populations in that part of Oregon.

PAULA BURGESS …including the Crooked River. But now talk is that with the re-licensing that FERC [Federal Energy Regulatory Commission] is doing, there’ll be a reintroduction of fish in the Crooked River system. Also, there’s a movement in the Northwest to remove specific barriers to fish passage. One interesting thing is climate change seems to be causing discussions of whether it’s more important to remove barriers to fish passage or keep the hydropower generated from damming water. It’s good we’re having a healthy debate in the Northwest about what our priorities.

NWNL Folks advocating the restoring the salmon and opening fish passages seem concerned that salmon would no longer have sustainable thriving populations in those northern tributaries due to climate change. But you’ve seen species of salmon in Idaho that have adapted to warmer weathers and are doing quite well.

SASHA TWELKER Well, California and Idaho are probably the best examples of fish adapting to warmer water. The John Day River system is one of the warmest, with 80-85º water temperatures in summer, but oit has deep pools for the fish so they’re gradually adapting. But can they adapt to climate change quickly enough to survive over the next 10, 20, 30 years? Some scientists believe it’s going to be very, very hard for fish. So those that have adapted to warmer water represent a very important component we need to keep and help survive so they can adapt.

It’s also important that wild fish have a full spectrum of biological diversity. Some emerge early from the spawning gravel, some emerge late. So they arrive in the ocean at different times and those timeframe become very important to their survival.

NWNL Sasha, your maps break down salmon distribution and locales by species.

SASHA TWELKER Yes. Unfortunately, the gray represents holes in our data; but they’re quickly being filled in. Our populations are rated from 5 to 16. Five indicates low proactivity, low abundance, low viability and a very hatchery-driven population. Sixteen is quite the opposite. Shown in blues and dark greens, the sixteens are almost 100% wild, which is great! And they don’t travel quite as far away from the coast. They stay quite close.

NWNL It’s nice to see there are lots of blues and dark greens here.

SASHA TWELKER Summer Steelhead are scored at 5, the lowest score given. Next is Winter Steelhead.

NWNL What about the Spring/Summer Chinook?

SASHA TWELKER The Spring/Summer Chinook are strongest. They have a very strong population in the John Day River system. Especially northward. John Day has excellent habitat conditions. You can see also good strong populations in Idaho’s Middle Fork of the Salmon River. Most of that pristine, beautiful habitat is in wilderness area.

The Fall Chinook are in the Deschutes, Sandy and Lewis Rivers – all doing very well.

NWNL Will the Sandy become stronger habitat for Fall Chinook when the Marmot Dam is decommissioned?

SASHA TWELKER There’s reason to believe that it won’t as it’s a very coastal system and not very far spread. This is its most southern extent.

PAULA BURGESS In the office we have a map of their original extent, which represents the most extreme extent of salmonids.

SASHA TWELKER The Coho Salmon are also coastal now.

PAULA BURGESS Coho used to inhabit much of the interior Columbia River Basin. Now their range has shrunk down to just the mouth of the Columbia, with their strongest populations on the Oregon side of the river.

NWNL Paula, what’s the cause of the Coho’s lower numbers?

PAULA BURGESS The causes include habitat degradation, high dams and hatcheries – all the H’s work together here. We have many main-stem dams, which makes any fish passage difficult. We have hatchery operations and if they produce large numbers of salmon, they compete with wild fish for food and habitat, notably spawning gravel.

The question is at what point do we exceed the food supply in the ocean? In Japan, where they produce mostly pink Chum, they’ve cut back on their production of hatchery fish. The returning pink Chum were coming back smaller and so they realized they were exceeding the carrying capacity.

We estimate we have five billion hatchery fish in the ocean. The question for us is whether we’re exceeding the carrying capacity of the ocean or its estuary environments. Also, the fish that we generate are genetically not quite as diverse. Although we can produce genetically diverse fish by very carefully setting separately timed runs, if the fish get out to the ocean and don’t have food because of climate change, then they’ll die off. Whereas a later returning, or an earlier returning, fish might find food. Thus, the population might shrink for a while, but then could regenerate.

SASHA TWELKER As to the decline of our Coho numbers – neither Coho nor Chum are good jumpers, so they can’t climb the fish ladders as well as other species.

NWNL Where on your map do you have the Sockeye Salmon? It’s my favorite tasting fish.

SASHA TWELKER It’s sad. Most of their population is limited to Wenatchee, the Okanogan, Red Fish Lake and the Snake River system.

NWNL And on the Snake River, the Sockeye are in only one spot.

SASHA TWELKER These fish are being kept alive. They are just hatchery fish at this point. One year there were only two Sockeye salmon returning. I think they were named Harry and Charlie. In the Deschutes River Basin, a couple Sockeyes made it up through the turbines of this dam. If they took that dam down, they believe that there’d be an amazing population that they might not even have to restock after too many years.

PAULA BURGESS That those fish survived passing through the turbines is amazing.

SASHA TWELKER Trout Unlimited and other related groups contend that the best way to keep the interest in those species up is by hunting, fishing, etc. One of their books saying North America has the best fishing, mentions one of our great trout rivers for trout fishermen, since its trout, like salmon, have adapted to warm water.

NWNL I think that Kenya and similar game-rich African countries will and should re-instate hunting, because that will support preservation of wild areas that otherwise would go. Tanzania has some hunting, but Kenya banned it in 1963, other than for some small bird hunting. But its reinstatement is being discussed more and more.

PAULA BURGESS How about the elephant populations? Are they on the decline?

NWNL Yes, elephants are declining big time – big, big, big time. Part of the issue has been about poaching. The CITES Conference outcome was a bit of a surprise when in an unique arrangement, they planned to lift the bans totally. But that has changed. As I understand, southern African countries with huge stockpile of ivory will be allowed a one-time sale.

PAULA BURGESS Really?

NWNL There were many at this CITES Conference wanting income from ivory. So, similarly, what to do about salmon? Do we use cheap energy from hydro, or do we protect salmon and what they contribute to the environment and our soul….?

SASHA TWELKER These management questions are tough. If we’re going to manage, if we humans are going to play God and manage species, then we must manage the system and the full range of species, not just do the thing which we do the best which is over harvest one pieces of the food chain until it’s gone. And then we over-harvest the next piece of the food chain, and the next. We need to harvest in ways that don’t cause our systems to decline.

Posted by NWNL on March 21, 2024.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.