Lake Turkana Viewpoints

Omo River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Omo River Basin

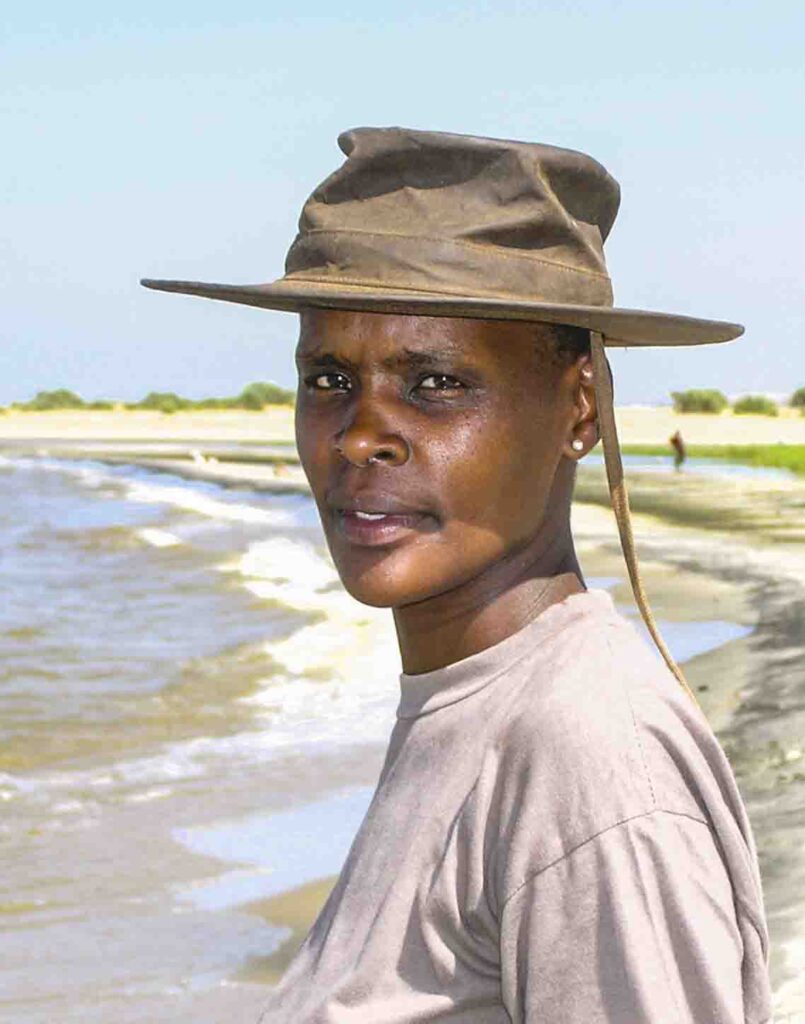

Joyce Chianda

Managing Director of Jade Sea Journeys and Lobolo Camp, Lake Turkana and Kenya

"Joe" Njogu Chianda

Brother of Joyce Chianda

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director & Photographer

VALUES OF THE LAKE TURKANA REGION

TURKANA – A UNIQUE DESERT LAKE

CHANGES in the LAKE’s FOREST AND FISHERIES

GIBE DAM’S IMPACTS on the LAKE & ANNUAL FLOODS

A GAP IN COMMUNICATIONS

GIBE DAM’S IMPACTS on the KARO & OTHER TRIBES

TURKANA CULTURE TODAY

POPULATION & WATER ACCESS

All images © Alison M Jones. All rights reserved.

It is said that Joyce can be found on a seasonal lagoon on the sandy western shores of Kenya’s Lake Turkana, chairing a meeting between flamingos and donkeys over disputed access to water in a seasonal lagoon. I first met her there in 2004 with her husband Halewijn Scheuerman, a multi-lingual Dutch explorer and co-manager with her of Lobolo Camp and Jade Sea Journeys since the early 1990’s, also interviewed by NWNL. Joyce’s Kikuyu background, business acumen and charm has made her a perfect hostess and spokesperson for the local Turkana fishing villages Kikuyu and their unique desert lake so critical to Kenya’s arid Northern Frontier District ecosystems.

Values of the Lake Turkana Region

NWNL Hi Joyce! It’s wonderful to be back at Lobolo Camp, here on the western shore of Kenya’s Lake Turkana. Let’s begin our chat with why you picked this spot for your camp?

JOYCE CHIANDA I believe it’s the only outstanding spot on the western shore. It has doum palms, water springs, a very healthy forest — and I believe it’s the only place on Lake Turkana that offers the sports we have..

NWNL What is the importance of this lake, way up here on Kenya’s northern border?

JOYCE CHIANDA It is a local lifeline for the people living along the lake. These Turkana people depend on this lake for fishing and their own livelihood.

There are other communities on the east side of the lake, including the Gabbra who use it to water their animals. On the northeast side, the Dassenach fishermen and pastoralists also depend on this lake. The lake is a lifeline for the tribes living on the shores of this lake.

NWNL And more broadly, does the lake benefit Kenya as a whole?

JOYCE CHIANDA Yes, it’s a national heritage. Several resources here supply much of Kenya’s electric grid, including nearby findings of oil – our “black gold.” The region also produces wind energy, on which the country now depends, as well as geo-thermal and solar power. Kenya also benefits from power generated by Ethiopia’s dams on the Gibe tributary of the Omo River – source of 90% of this desert lake’s water.

But Kenya depends on this lake for more than electricity. The people of Kenya depend on this lake for their fishing industry and their cultural heritage. The government needs to respect that.

Turkana - A Unique Desert Lake

NWNL How would you describe the lake’s setting and its unusual desert ecosystems? How is it different from other lakes in Kenya?

JOYCE CHIANDA Turkana is one of the biggest desert lakes in the world and has two UNESCO World Heritage Sites featuring the Leakey family’s fossil discoveries. It’s also a lifeline for the people who live here today. We have wind and an aquifer that’s been found holding a lot of valuable fresh water. These are things that benefits the country and the local tribes living around Lake Turkana.

NWNL Weather and climate also seem to make this large desert lake different.

JOYCE CHIANDA Yes, this region has very harsh weather. The sun, even early in the morning, can be very hot. Temperatures range from 45º to 20º Centigrade [113º to 68º Fahreneit]. This variation and the wind do affect the lake and its water level. This lake. in the middle of the desert, doesn’t have any outlet. Being an endorheic ecosystem, it is quite sensitive; and evaporation takes a large toll on salinity and quantity of its water. Thus, I think the lake needs careful consideration regarding its utilization. It’s critical that the government consider how to take care of this lake.

NWNL Has the lake, its weather or surroundings changed since you came here 35 years ago?

JOYCE CHIANDA The first time I came here was 1981 or 1982. The desert was a paradise. At the southeast end of the lake that first time, I fell in love with Lake Turkana. I still remember seeing South Island across the lake and a bit of Suguta Valley. I instantly fell in love with the scenery. There’s been no turning back for me. It made sense, so I became part of the community.

Since, I’ve seen a lot of changes – especially the loss of forest that surrounded the lake: doum palms, indigenous trees and other vegetation. That forest contributed to the rains that in the past came regularly, or at least once in a while. Human activities are part of this destruction.

For instance, now we’ve yet to get rain. We now can go up to three years without any rain, but that takes a toll – creating the conditions we experience today. And the population grows; and human activity expands. That means destruction.

NWNL Does this loss of trees impact local Turkana and others around the lake?

JOYCE CHIANDA They suffer. Having lost the natural forest is like “No Water No Life. No trees, no rains, no water. Now there is no water coming into Lake Turkana, so its water level goes down. Even if not significantly, it still goes down. That changes the quality of the water.

The water-table level impacts the local people and their domestic animals, even though they depend on so little. They suffer because even if there is water after the rains, usually they must go to the wells the dig in the luggas [dry stream beds]. When it is very dry, despite how deep they dig, they can’t reach water. That takes a toll on their animals and thus human lifestyles since they depend on animals to eat or to sell.

So, the lake suffers from both weather and ongoing human action. Changes and challenges continue. The question is what to do about it.

NWNL With less rain, therefore fewer animals, are fewer people living here now?

JOYCE CHIANDA I think so, because the younger generations are moving to urban areas to look for jobs. They leave the villages because their animals are dying and there’s nothing to do. More and more people move away to find other ways of living or earning money. You don’t find young people in the villages today, unless they’re home on school holiday.

NWNL I know this is desert, but is there any farming here?

JOYCE CHIANDA I think probably only 0.0001% farm. Farming can only happen after the rains or near where water collects in those very few depressions and water pans that are rich with silt after the rains. I’ve seen A few people trying to grow short-lived maize and beans, those that mature in one or two months. Otherwise, there is no farming.

NWNL Does weaving palm-frond baskets or thatching roofs offer profitable livelihoods?

JOYCE CHIANDA Yes, but there are middlemen, so local farmers still get peanuts. The middlemen make money. Locals will sell farm products at a throwaway minimum – but they do earn a living. But they also use doum palms to build their homes, so that also destroys their only vegetation since farming destroys the forests, already threatened by weather changes. Thus, they are tearing down the little they have – and so the cycle of poverty goes on.

NWNL Do the Turkana fish for a living? What fish are here? How do they catch them?

JOYCE CHIANDA Locals normally fish down on our beaches. When they use the nets, they catch mostly tigerfish. They call them bonefish. Commercial fishing is for tilapia and Nile perch. Any other fish they catch, they consume among themselves. What they catch with nets goes to their own community. Whoever helps in pulling up the nets gets fish.

NWNL Have the number of fish in this lake changed? Are there enough fish to support the people here as either food or income?

JOYCE CHIANDA No. Fish numbers have gone down drastically. probably mostly due to overfishing. I don’t know how to quantify that: but in my opinion, it is mostly due to the commercial fishing for the Congo market. In the past, fish was dried and sent to Mombasa (on Kenya’s coast). I think the intestines went to China. Now instead of going to Mombasa or being shipped wherever, the dried fish goes to Congo via big, converted trucks with coolers. Most fresh fish goes to Nairobi.

NWNL What percentage of the Turkana people around the lakeshores are fishermen?

JOYCE CHIANDA The majority of the Turkana people fish; but the Dassanech people on the other side and in the Omo Delta also fish. That is why they clash with the Turkana.

NWNL Ah! they are all fishermen – and they’re rivals.

JOYCE CHIANDA Yes, and their rivalry is over the fishing grounds. The Turkana have dominated, except in the Delta which the Dassanech believe is their territory. The Gabbra and Samburu on the other side are not fishermen. because they are kept away by the Dassanech.

NWNL Have fish from Turkana added protein to Kenyans’ normal diet of maize?

JOYCE CHIANDA In the past, we used to have fish from Turkana. Even City Market, in Nairobi had fish from Turkana. Some used to be taken to Kisumu on Lake Victoria, because they consume quite a lot of fish there. But the dry fish go to Congo and Uganda.

NWNL It’s strange they’d take fish to Kisumu, where they have their own fish.

JOYCE CHIANDA But Lake Victoria also is overfished. There was a period when there were no fish there. Now, eating fish in Kisumu is more expensive than in Nairobi, because they’ve always consumers of fish, so there is a demand, unlike central Kenya where people eat maize.

NWNL Has the availability of fish in Lake Victoria come back up?

JOYCE CHIANDA There is a comeback in Lake Victoria, but no more of the big catches from the past. There are border issues between Kenya and Uganda and too many people fishing. The ecosystem is so harassed, and growing populations add more pressure Here on Lake Turkana, the pressure is the convoys of trucks going to Congo with our fish.

Gibe Dam's Impacts on the Lake & Annual Floods

NWNL What impacts do you see of the Omo River’s Gibe Dams? Have they or could they lowered the level of this lake?

JOYCE CHIANDA There is that possibility, but up to now I’m not sure it’s a very big impact. But, as my brother Njogu explains, you don’t see algae or the water hyacinth now. There was a time that we thought that even the Omo would be full of this water hyacinth. But it seems that because the strong flow of Gibe Dam waters rip away “the green carpet” by the roots.

NWNL The green carpet?

JOYCE CHIANDA The water hyacinth was a carpet of green leaves floating over a very big area. The carpet started in the Omo Delta; broke away during the high annual floods; and then just float down onto the lake. But not anymore. So, there are impacts from the damming the Gibe River and irrigating Asian corporate farming there now. The lake level is down. But we don’t know if it’s the impact of Gibe Dams, or evaporation, or the little Turkwel or Kerio Rivers.

NWNL When I was with your husband Halewijn in the Delta, he pulled up the hyacinth to show me its mass of tangled roots. He explained they have choked Lake Victoria, but not the Omo River because its yearly 60-foot floods tear the water hyacinth from its roots. So, I can imagine they will choke the Omo now the Gibe Dams have stopped that flooding.

NWNL 90% of the lake is filled by the Omo. Has its Delta changed due to the Gibe III Dam?

JOYCE CHIANDA The Delta is harassed since there’s no water from the annual floods. It needs the rains and the floods they bring – but they’ve ended because the dam regulates Gibe River flows. Farms need water, so farming patterns have changed. Today’s the Omo’s vegetation and riverine forest are gone. It will be another desert, due to this big-scale farming and the damming of the Gibe River. Basically, the Omo is also dammed now because little water reaches the Omo Delta.

NWNL What’s the effect on the tribes who practiced flood-recession agriculture?

JOYCE CHIANDA I hear they have now farmed for the first time in a few years. They went back to their farms on Lake Dipa where they would retreat if there were no rains.

During three years filling the Gibe Dam, there were no floods and thus no farming. There were devastating effects. That then contributed to devastation in the Delta. I don’t think many Delta channels exist anymore. We thought the floods would escalate fighting in the Delta among the Dassanech and the Turkana. But that didn’t happen. Probably the Turkana kept to their northern corner of Lake Turkana and the Dassanech kept within their territory. So little is happening now in the Delta.

NWNL There are several 6,000-year-old tribes on the Omo who were successful self-sustaining by using flood-recession agriculture. Now that Gibe III Dam is built, a New York Times article I gave you says the tribes keep waiting for the floods and the rains, saying “We don’t know why this is happening.” And the dam representatives try to explain, “There’s a dam that holds back the water.” But these tribes don’t understand such concepts because they’ve never seen a dam.

JOYCE CHIANDA Yeah, that’s so. They remain hopeful, despite the documentary they’ve been shown. To them the lack of floods is God, a natural phenomenon. They do traditional things to please the gods so rain comes. When you explain these dams, they don’t understand. But they know something is happening because they have never seen it like this.

Outsiders say, “You need to educate the people.” But first, the people must understand what’s happened, because it affects them. They’ve lost their revenue as they can’t farm, and their animals struggle without water and vegetation. The indigenous Omo Delta villagers need healthy animals and a healthy ecosystem – which no longer exists there.

NWNL What’s happened to these village, for instance the Karo villages I visited so often.

JOYCE CHIANDA As you know, before and during the floods they moved to higher grounds. After the rains, they come back to start farming. With the rains comes the silt, so the farms are very rich. These days I don’t think they move, although last year I understood they released the water. They say the dam broke its banks and water came down unexpectedly. So many people were misplaced, many were drowned. All was damaged I don’t know for which villages. That was the first time they had the floods.

They want to farm now at Lake Dipa. But that’s in the area new foreigners use for farming. The irony of the whole thing is some of the Karo are beneficiaries of this foreign farming, since young and able Karo are working for these foreigners and now having a modern life.

NWNL What do the foreigners grow?

JOYCE CHIANDA At Dipa they’re growing cotton and sugar. Further north, just sugar. Near the Karo village of Duse they’ve planted jatropha, an ingredient in diesel. Sunflower farms are in what were cotton fields near Omorate.

NWNL What do you think will happen to the Karo culture? There were only three Karo villages, but they had a very strong culture.

JOYCE CHIANDA I think that strong Karo culture is disappearing very fast. Today some go to a school in the village. But most from Duse are taken to boarding schools to Turmi (Hamar country) and Jinka. Much in Duse has changed. Today it’s full of modern gadgets: smartphones, music, sunglasses, even swimming costumes! It’s like Miami Beach.

NWNL In Duse, there was a “Parliament Building” where all the men gathered to make village decisions by consensus. What’s happened to that approach to their community government?

JOYCE CHIANDA Community government and that great building is still there. I think it still plays its same role. But I think some people in Duse have been compromised. The Karo are at a crossroads: modernity versus their past, as they face many contradictions. They’ve learned the value of money and now know they can have a better life. As I see it, their culture is dying.

NWNL Then, is their parliament – governed by consensus – able to function now?

JOYCE CHIANDA With difficulty. Some are pulled this way; others that way. Their traditional way of consensus they’ve practiced all these years is facing the Ethiopian government. Educated Karo understand what’s happening in the modern world, because some are going to America and see how it is there. They return with stories and photos. Some say “Wow,” but Karo elders still tell their people, “Our tradition is the best way to go.” Then someone comes, looking like a Hollywood movie star, saying, “No.” And the Ethiopian government tells them that being naked is basically a crime. They are confused. Most of them don’t know any more if they should take their girls to school or not.

NWNL If they lose their culture, what do they lose?

JOYCE CHIANDA They lose their values. They become “normal.” Losing your culture is losing your identity at some point. I am a Kikuyu, and I regret that the Kikuyu culture died. Sometimes I wish we still had our traditions. There was something beautiful about them. And I think something is lost with the modern way of living. I think something will be lost for these villages and their tribes. For example, Kikuyu people now are trying to go back to revive their culture. But it can only work once – the original time. When it is lost, it’s lost for good.

NWNL It’s like the extinction of a species.

JOYCE CHIANDA Yes. I think one day we’ll probably all be equal. Because when all tradition is lost and thrown through the window – when we’ll have all gone to school and speak one language, we’ll think more or less the same. I feel we need to think where we’re going.

NWNL Are the Lake Turkana people leaving their villages for Lodwar, or for bigger towns further south? What happens to Turkana youth who go to the cities? What’s their life there?

JOYCE CHIANDA It depends. It’s hard to make it “down there.” You may end up in the slums on the streets — or maybe get a job or be domestic help in someone’s home. Many don’t go far because Nairobi is too scary, or they want to stay near here. So they merely go to Lodwar, Kitale or Eldoret. Of the few who go to Nairobi, some make it and some come back.

Now with Kenya’s political devolution and new Constitution, much has changed. Money reaches many more people, or at least benefits people one way or the other. Yet, most who get money directly are in towns. People in villages don’t benefit.

Now that there is access to money, they know its value and what it can do for them. They know they can access ATMs, and probably access the life they want. That’s changed people and so they’re going to town, whether they will find a different life or not.

NWNL You said villages are crumbling now that they own private house and enclosures.

JOYCE CHIANDA Yes. People are becoming individualistic. They now have access to the civilized world – or at least the modern world and new technology. People also have access to education and so are more confident they can leave the village, be on their own, and have mobile phones and Piki Piki [motorbikes]. So, they don’t need the community for survival.

They are more informed than before. News reaches them. They can operate their mobile even though they can’t read. They dress and no longer show their bodies, because now they feel private – no longer part of the communal bond that’s being broken. With modernity, they become like the Western world, the civilized world.

NWNL To me, the Turkana tribe seems more educated than those along the Lower Omo. What percentage of the young Turkana have gone to school?

NJOGU CHIANDA If there is food, they’ll go.

NWNL Are they building more schools?

JOYCE CHIANDA Yes. The county government’s highest priority is schools and medical health facilities. They are trying to keep kids in schools, so there’s food for them and health education. Where there is a school, now there is a medical center.

NWNL But are there bore-holes or water pumps at school?

JOYCE CHIANDA There are some bore holes.

NWNL So where do these communities get their water?

JOYCE CHIANDA They walk to Lake Turkana or the luggas, the dry riverbeds. They dig wells in those luggas after the rains. When no water is left in the holes, they go deeper.

NWNL How long will somebody walk to get water?

JOYCE CHIANDA Some walk 20 kilometers. Some do so two or three times a week, if they live far from the luggas. Now the county is building more water pumps and water pans to collect the rain. That helps their lifestyle because then they and the animals don’t need to walk so far.

NWNL Do people drink the water from the lake?

JOYCE CHIANDA Yes. Also, they cook and wash with lake water because they believe it has salt. Thus, they don’t need salt in their food. They don’t use water from the springs because they think lake water is better than the spring water.

NJOGU CHIANDA Or even better than bottled water.

JOYCE CHIANDA They think bottled water gives them the flu. Even our own staff doesn’t drink this water. For them, lake water is number one.

NWNL Is the population here growing, staying the same or getting smaller? It seems like it is getting smaller. They seem to understand that sending more children to school means they need to work harder. But they say more children can create wealth – especially if they’re girls?

JOYCE CHIANDA Girls equal wealth because when they get married, parents get a dowry – probably a lot of goats. Sometimes you can get 300 or 500 goats for one girl. You can get camels and donkeys, even a bull…. If you have boys, then you’re a poor man.

NWNL Do you think the government will ever install pipes to deliver water to communities? The water pans they put in to bring water to the communities don’t work if it doesn’t rain. So, they’re not terribly effective.

JOYCE CHIANDA No. It’s not the government that put in boreholes here. It was NGOs, funded by USAID. They’re still very effective here and some have been sponsored by government. But most don’t work. Those that do now are by county government.

NWNL How do you get your water here at Lobolo Camp?

JOYCE CHIANDA We have spring water from the ground.

NWNL Who has access to the recently discovered aquifer near here? I hear it’s very deep.

JOYCE CHIANDA The Turkana County has access, I think. But it’s a national resource. For instance, if we find gold, it belongs to the government. A very small percentage of people in Lodwar are benefitting from that aquifer now. At some point, there’ll be meter and you’ll pay for your water to the county – as in Nairobi. So, here, it would be the Lodwar WRMA [Water Resource Management Authority] who put in the meters and will charge for water from this new aquifer.

NJOGU CHIANDA In Kenya, the WRMA’s charges or collects payment for water use. I don’t know how effective it is…. Whoever uses water anywhere should account, so it is known how it was used. Fees are paid to the WRMA so it can develop other water projects.

The reality is when you have a river next to you, you drink. When you have a spring next to you, you drink. If you are take water from a spring, you pump it. But once you are supposed to pay for every liter from that spring, you are more sparing in your use.

Here, we are under community license with a meter running, and we contribute to the community every month. In this region water accessibility is cordial. Only where there is farming, do you have trouble with water.

NWNL Thank you both for your time and thoughts shared here under doum palms, looking out on your beautiful silvery lake. I hope there are not too many more changes. This lake is a treasure!

Posted by NWNL on September 16, 2023

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.