The Cradle of Humankind

Omo River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Omo River Basin

Halewijn Scheuerman

Anthropologist, Explorer and Guide

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director and Lead Photographer

Boreholes (i.e., wells) don't solve the problem. NGOs can't bring the rains to revive pastures, so livestock still die. Birth control would stabilize the population. But anything like family planning is culturally taboo. --Halewijn Scheuerman: Anthropologist, Honorary Warden of Lake Turkana N. P.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Halewijn Scheuerman grew up in the Pyrenees; went to school in France; skied in Morocco at age 14; and worked for a Ph.D. in Political Science in Utrecht. After crossing the Sahara Desert via motorcycle, he adopted Africa as home and married Joyce Chianda in Kenya. They launched “Hiking and Cycling in Kenya” and led safaris all while raising Jelida and Ngalivia, their two bright, beautiful daughters.

Halewijn first visited Lake Turkana and the Omo River in 1993 when he focused on the traditions of the local tribes. His “Jade Sea Journeys” offered his guests the only camps running boats on the Omo River, through the Delta and across Lake Turkana. His interest in anthropology became one of full immersion. He became initiated as a Hamar elder after his bull-jumping initiation. Sadly, Halewijn died too early in an accident in Kenya.

Under his wife Joyce’s expertise, Jade Sea Journey’s continues to offer unique opportunities to explore Halewijn’s beloved “Jade Sea” (Lake Turkana) and the Omo Valley’s “Cradle of Humankind.”

The Omo River System

NWNL Halewijn, it’s great to be back in southwestern Ethiopia, staying with you again on the banks of the Omo River. Let’s begin by defining this river system.

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN The Omo River is about 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) long. Its main tributary is the Gibe River, which is now being dammed to generate electricity for the welfare of Ethiopians. After the Omo runs south a bit, it moves westwards crossing an area called Keyafer, where coffee was discovered.

From there, the river grows and meanders south, carrying off a lot of topsoil into this Lower Omo Valley where we are now. The areas where the Omo silt comes from are probably quite eroded now. The Omo deposits that sediment on these banks during its slow floods [that can rise 60 feet]. Although these floods recede, the Omo never dries out. It’s a significant river that flows continuously.

NWNL Usually flooding, often exacerbated by deforestation in Africa, destroys the stability of the banks, but here it seems flooding is beneficial to the local farming.

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Absolutely. The more the river floods, the more it breaks the banks; and then the bigger the area of food production will be the following year. After the river recedes this year, there’ll be big areas of sorghum production. Even the Nyangatom village we just visited has big flooded areas now. All that water carries silt and fish that will die and enrich the soil. Breaking the banks is beneficial here – unlike the Katrina effect in New Orleans.

That silt allows the traditional Omo people to practice flood-recession agriculture as they have for thousands of years; and that silt ensures successful harvests. Thus, the silt deposits allow them to provide a healthy diet for their children. They sell their surplus, in exchange for livestock and other commodities, to pastoralists like the Hamar who live on the dry margins of this valley.

The Hamar and other pastoralists around the Lower Omo don’t practice flood-recession agriculture; but they use the Omo River for watering their cattle. So the Omo’s water and silt is vital for many, many people.

NWNL The Omo River is an “endorheic” river since it never reaches an ocean, or a larger river that reaches an ocean. Ethiopia’s Omo River ends up in Kenya’s Lake Turkana. Can you describe this terminus that’s neither a confluence nor an estuary?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Before entering the lake, the Omo splits into many arms to form a delta before it enters Lake Turkana. The Omo Delta is about 1,000 square kilometers, an area that has changed along the years. At the end of the 60’s, a very big group from Chicago University came here to investigate the Delta and then published a geological and geographical history of the interaction of the Omo with its delta and Lake Turkana.

If you compare satellite pictures of the Delta from 20 years ago to those from today, you’ll see that it’s changed. I can tell from here on the ground that it changes everyday because there’s a mass of water and a lot of silt – the building blocks for a delta. On the lower side of the Delta, as more water comes in [during annual flooding], the lake will rise and the delta will diminish in surface. So, there is this ongoing interaction between the lake and the river.

NWNL From the Omo Delta, this water all flows into Lake Turkana, the world’s largest desert lake.

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN The Omo River reaches its terminus at Lake Turkana (called Lake Rudolph in the past), contributing about 95% of water flowing into Lake Turkana, especially now that the Turkwell and Kerio Rivers have been harnessed by Kenya with dams. This is an alkaline lake, although it still harbors what is considered sweet-water fish, like Nile perch and tilapia. Although Lake Turkana is a fish producer, no large-scale fishing takes place.

Lake Turkana’s surrounding environment, apparently hostile, is nothing like this green, lush environment. In 1888 when Count Teleki reached the lake, he expected to find something lush, like Lake Victoria. But, there’s nothing there other than volcanic rock, a lot of wind, and the rugged Turkana people, who survive in that rugged environment.

Flood stages in Lower Omo River Basin (L) and Omo Delta entering L. Turkana (R)

Omo-Turkana Basin / Paleo-History

NWNL This Omo River/Lake Turkana watershed has a long history.

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Yes, the geological history along the Omo River and sediments in the Turkana Basin show that silt has been part of this river in immemorial times. We think this silt we see today was from early human activity in the highlands of Ethiopia. What else would explain this massive silt that came down through the proto-Omo, and created those layers we see in Koobi Fora and certain cliffs in the Lower Omo?

We modern humans tend to look at the Earth from the very short perspective of our own life expectancy. Sometimes we dig into books and go back 2,000 years, but that’s nothing. We tend to think that everything we see is new, but it’s not new.

In the case of the Omo, the silt has been there since the river existed. It has transformed the environment, sometimes for the better. It helped preserve the beautiful fossils in Koobi Fora we find that help us understand where we came from.

Paleontology at Koobi Fora in Kenya’s Sibiloi NP on Lake Turkana eastern shore

NWNL Is this truly the “Cradle of Humankind?”

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Yes. Until any further new discoveries, we can consider this part of Omo River Valley – a side arm of the Rift Valley and Lake Turkana – as an important part of the “Cradle of Humankind.” The region from northern Ethiopia to northern Tanzania harbors the most important ancient human remains. So, the Omo Valley is important for paleontology and is expected in the future to play a role in discovery.

NWNL What discoveries have there been here so far?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN The most important finds within this Omo and Lake Turkana Basin have been of Homo erectus, our forefathers. The most important research taking place at the moment is in the Illeret River above Koobi Fora by the new-generation Leakey – Louise Leakey – with assistance from her mother, Dr. Maeve Leakey.

There’s now a controversy among the latest discoveries concerning Homo habilis versus homo erectus. Those species lived in parallel times. So, as these discoveries take place here, the Leakey’s daughter steps in the shoes of her parents to dig in this very important area.

At the end of the sixties, Richard Leakey was a member of an American-Kenyan-French expedition here on the Omo, taking care of logistics. On his way flying down to Nairobi one time, he flew over Koobi Fora and realized it could harbor some interesting sites. Borrowing an available helicopter, he landed in Koobi Fora and the rest is history.

It all started with excavating for Homo erectus, Homo habilis and more primitive species like the Lucy. As well, there have been important Ethiopian finds in Harar, Afar, and even in the Omo Valley. So we can all think that we belong here. Maybe that’s why I came back. I came back here to spawn, like the salmon. We all have this memory.

NWNL I’ve heard this referred to as a “genetic memory.”

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Yes. There’s a “pull” here, more than just a culture. We tend to be too brainy, but we also have guts. I think we have “a genetic memory.” It goes back very far. There’s no scientific proof, but I feel it.

Many people have that sense of recognition when they set foot on the continent of Africa. They feel this is “the mother country.” I feel at home. There are many people that feel it. I don’t want to idealize Africans, but in general I feel many Africans have something that I miss. I cannot describe it. It’s not lifestyle. It is something that I would like them to share with me.

Lake Turkana is an integral part of the Omo system. Without the Omo, the lake would die. The lake has a tremendous force and influence on my soul. It caught me when I set eyes on it for the first time in 1979. At that time, I was still busy with my dissertation, but I knew I’d come back. And I did, I came back to “The Cradle of Humankind.”

NWNL I’m glad you did. What you’ve taught me about the Omo Basin was critical to my vision of this project. I first conceived this project as “The Waters of Ethiopia,” and then expanded to include North America. So NWNL certainly sprang out of this Rift Valley, just as humankind did.

Volcanic sand and steam emanating from crater’s edge on Lake Turkana’s Central island

Water Quality and Accessibility

NWNL Since NWNL focuses on the importance of protecting our water supplies, I want ask how would you rate the river today in terms of water quality?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN I can only judge what I see in the Lower Omo. It’s healthy. It’s healthy. It’s healthy. There is a lot of silted water, bringing nothing but benefits. It is “new manure” for these fields every year. It is food for “the nursery fish” in Lake Turkana and “the cradle fish” in shallow nurseries in the Delta. Certain times of the year, as the fishermen know, millions and millions of lake fish go to the delta to feed because it’s a very rich environment.

The Omo water that flows in the lower part of the valley is germ-free, in principle. There are no big cities. There are no industrial developments in the upper watershed. The Omo flows for a long distance while exposed to sun. So, instances of people getting waterborne diseases from drinking directly from the Omo are rare.

NWNL How would you rate water accessibility in this watershed?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Although these floods recede, the Omo never dries out. It’s a significant river that flows continuously. The Karo farming communities use the river during all seasons. Other pastoralist tribes, including Mursi, Hamar, Nyangatom use the Omo during the wet season to graze and water their cattle. Then at the end of wet-season they move upland, using springs and high water tables in seasonally dry riverbeds.

The Dassanech however move to higher grounds during the wet-season grazing [to escape high river levels.] The moment the dry season comes, they return to the Omo Delta where they have plenty of water– almost too much.

NWNL Where do human residents get their water?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN At the moment, many villages have water nearby. The river is so high that it has broken the banks and is flooding big areas. So right now, those women don’t need to walk very far to fetch water. But under normal circumstances, women walk to the river, dry riverbeds or springs – depending on what is nearest.

NWNL Yesterday we had a long walk with girls carrying water to their village. Does that impact them physically? In Addis, The Fistula Hospital cares for pre-teen girls, pregnant from rape or forced marriage. With pelvic bones stunted from years of carrying water, their childbirth can last days. Often the baby dies, or they die. If they live, they’re incontinent and banned from using the village well. Do you see that here?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Yes, girls who are twelve, thirteen years carry twenty kilos (45 pounds) of water on their head for long distances. What you’ve described may happen, but it is not generalized. I don’t think this problem happens often here because normally the Omo people build their villages and settlements less than an hour from a water point.

That’s a maximum reasonable distance – say forty-five minutes to one hour – for fetching water in pastoralists’ communities. That’s much nearer than many other East African pastoralists I know who can live four hours from water points. They accept higher than maximum distances of water because they have to spread out to graze their cattle.

For example, in Kenya’s Northern Frontier District, Gabbra in North Horr do not live near water. Some live three or four hours away. Some women use donkeys or camels to collect water [at far-away oases] when water is very distant and days away.

Water Users in the Omo-Turkana Basin

NWNL The Lower Omo Valley is home to pastoralists with cattle and goats and to farmers practicing flood-recession agriculture. But they seem quite mingled. Can we group those who live and work in this river basin – the “stakeholders” – by their locations?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN The six main Lower Omo stakeholders are:

• the Karo – who are farmers;

• the Mursi, Suri, Nyangatom (called Bume, pejoratively) – who are agro-pastoralists;

• the Dassanech – who are agro-pastoralists living in the Delta.

The Hamar, who are pastoralists, are not main Omo River stakeholders, because they live mainly in the mountains. They do use the Omo though because they take their cattle to the river for water; and they graze them on Lower Omo River lands leased or borrowed from the Karo.

Further downstream at the southern end of the Omo Valley are the Turkana people, who are pastoralists. They inhabit the Omo Delta which spans the Ethiopia-Kenya border and on the northern and western shores of Lake Turkana.

Communities on western shore of L. Turkana depend on the bounty of dwindling fisheries.

NWNL Do you consider yourself a stakeholder?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Yes, I am a stakeholder as well. I use this river for tourism, transporting my guests with my Jade Sea Journeys boats. Without the river, there’d be no tribes on the Lower Omo, and I’d have no resources to offer to my guests.

NWNL What other stakeholders use the Lower Omo as a resource?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Besides a hunting camp down river, I don’t know of any other tourism-related stakeholders on the Lower Omo.

[Editor’s Note: As of 2017, oil exploration companies as well as commercial cotton and sugar plantations are recent stakeholders, benefitting from new irrigation pipes running down from the Gibe Dams. Such Asian agricultural concerns bought land from the government after the indigenous tribal villages were moved off the river.]

NWNL Who are the stakeholders on the Upper Omo?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Upriver, the river runs very fast and flows right through the farms of the people that live there. Thus it doesn’t leave any sediment along the banks, so people there don’t practice flood-recession agriculture. The main stakeholder in the upper tributaries is the National Power Company of Ethiopia, which is building five hydropower dams on the Gibe River.

Upper Omo Basin/Gibe Dams

NWNL Thank you for that sketch of the Omo River Basin and its people. You just mentioned the five new dams on the Gibe River, an Omo River tributary. This cascade of dams seem to be “the elephant in the room” in any discussion today on the future of the Omo River Basin. What is your assessment of the impacts of the current and future Gibe River Dams?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN The Gibe Dams will create a 1,000-megawatt hydroelectric plant that will send power to Addis Ababa.

[Editor’s Update: In 2017, the Gibe Dams’ approximate power in MW:

Dams in operation: Gibe I (184 MW); Gibe II (420 MW); Gibe III (1870 MW).

Dams to be built: Gibe IV, aka Koysha, (2000 MW); Gibe V (560 MW).]

There is talk of also selling this power to Kenya, Sudan and other countries. If so, this dam will contribute revenue to the state of Ethiopia, which takes care of education and healthcare of its people, including those in the Lower Omo. So, in that case, all Ethiopians would benefit from these dams.

Additionally, if you assess Addis Ababa today compared to ten years ago, you’ll note the urbanization happening. This is late in coming if you compare it to all other African countries. But the government is organizing and there is economical development. So one way or another, Ethiopia needs electricity.

NWNL So overall, will the Gibe Dams be beneficial for those in the Omo Valley?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN I have absolutely no idea. I am not in a position to judge if the Gibe Dams are going to have a dramatic impact on the people in the Lower Omo. Emotionally, I would say, “This is bad;” but we’ll see. It is not known if the ecological consequences of the Gibe Dams will affect the livelihood of people practicing flood–recession agriculture.

I don’t know if they’ve accounted for the livelihood of the Lower Omo people. I don’t know whether an Environmental Impact Study has been made. If it has, I have no knowledge of it.

[Editor’s Note: The Gibe III Dam was built before conducting an Environmental or a Cultural Impact study, despite the Ethiopian Constitution requirement to do so.]

NWNL How will the dams affect the Dassanech and Turkana downstream of Ethiopia’s Omo River in Kenya’s Omo Delta and Lake Turkana?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN As far as I know – and I’m not sure – I heard the Kenyan government was not consulted, nor were Kenya’s Turkana fishermen. They were not asked, “Suppose that the river starts flowing less and the level of Lake Turkana goes down….” They weren’t told, “This will be the consequence….”

Pastoralism is the Lower Omo Valley

NWNL The Turkana and Dassanech are pastoralists in the Delta and Lake Turkana terminus of the Omo Basin. And I know there many pastoralist tribes in Lower Omo Valley, where we are now. But when away from the river, it seems there is no water and no people.

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN It’s only “apparently” no people. You didn’t see them or their grazing cattle, because at this time of year they go to the mountains, where there are a lot of springs. Not all the Hamar take their cattle into the Omo Valley to graze and drink from the Omo and Mago Rivers. They also graze in the mountains where they find food at the natural springs. They can often dig for water in dry riverbeds of seasonal rivers.

NWNL Do those immense dry riverbeds, so very clearly seen as we flew in, provide water? Do they ever reach the Omo River?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Some tributaries do reach the Omo, like the Kesquay River, famous as the Hamar tribe’s river of demarcation. Some seasonal rivers reach the Omo, or its Delta, when monsoon rains race downhill. Not all seasonal tributaries dry up completely.

Pastoralist tribes, which include the Mursi, Hamar, and Nyangatom people, move away from the Omo at the end of wet-season grazing. They then use upland springs and high water tables in seasonally dry riverbeds.

Flood-Recession Agriculture

NWNL To focus on current lifestyles on the Omo, tell us more about the traditional Omo flood-recession agriculture that is practiced above the Delta.

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN The beauty of this river is that it meanders. There are 500 kilometers of Lower Omo banks, which adds up to 1,000 kilometers when you count both sides. Not every meter of these banks are used for this flood-recession agriculture, but a third of the area is useful. As soon as the annual floods begin to recede from the top of these banks and people are sure the river won’t come back up, they start planting.

As the river continues to recede, they continue planting down the bank. By the time they reach the lower part of the bank, the upper part is ready for harvest. The harvest is a time of plenty when people are happy. It’s the time of a lot of ceremonies. This year’s floods are very dramatic. Everybody has every reason to be happy. The areas that are flooding will be fertile fields for months and months.

Besides using the banks of the Omo River, the Karo also use Lake Dipa. That lake, like other seasonal wetlands, fills and empties depending on the floods of the Omo. It’s been dry for a long time; but now it’s full again – and full of fish, including a lot of Nile perch. As it recedes, crocodiles there will go back to the Omo River and the Karo will start planting. They say this is their bank account because the floods actually create an alternative for an irrigated farm. It’s a natural version.

The Karo appreciate the lake’s flooding phenomena. All of them say, “We depend on Dipa. Dipa’s been dry, but now we’ll have many acres to farm.” When the lake recedes, they’ll have hundreds and hundreds of acres of very fertile land that will produce well for them.

Sorghum, a vital crop in arid Omo Valley, only needs water when its seeds are first planted.

NWNL Are there criteria that determine which crops they plant?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN They plant sorghum, beans and nowadays maize. There’s no specific crop they plant on the upper part, nor a specific crop for the lower part. Sorghum, an indigenous, drought-tolerant African plant, is their main crop. Sorghum will grow with only the dampness from flooding in the soil, and doesn’t need any rain after it’s planted. The Turkana will even grow sorghum in certain appropriate patches around Lake Turkana if there’s been a flash flood that lasts five or six hours.

Maize, although not native, is also a successful crop that people plant in the lower Omo. They plant maize when they expect rains, because, unlike sorghum, maize needs more than just humidity in the ground from flooding.

River Fluctuations/High Floods

NWNL Is this flooding higher than the usual?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN This high flooding is due to an abnormal weather pattern. We don’t know if it is temporary like ten years ago, if this is an El Nino, or not an El Nino. If it is El Nino, we will be okay next year. But if this is a continuous pattern, for sure the Dassanech will lose a lot of land as Lake Turkana rises.

[Editor’s Note: The 2008 flood was also extremely high. However retention of water, especially during the filling of the Gbee III Dam reservoir has lowered water levels.]

Changes in the lake’s water level are not abnormal. Lake Turkana has known different levels all throughout its history. We know from history that increasing and diminishing levels happen relatively often. We know that Lake Turkana in the 20th century has been 15 meters higher than today – and it’s also been lower than today.

In geological terms, it happens very often. It’s rapid. So, we should not dramatize rising and lowering water levels because it has been happening long before humans starting building dams, and long before we polluted the atmosphere.

NWNL What about worldwide news of the deadly Omo floods last year [2006]?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN It is said that there was a southern flood at night that took people by surprise, especially in the Delta. I wasn’t here, but I heard the water level raised several meters in a matter of hours.

The Omo can rise several meters in two days, but when it rose several meters in an hour, it took many people by surprise. Cattle were drowned and taken into the lake. Some villages were under water. People surrounded by water had to be rescued by helicopter. Those images were on international media.

The “official version” says force of nature caused this flood. But the Omo never floods several meters in a matter of hours. So, this was a manmade phenomenon. It is said – although not “officially” – that this was due to the releasing of water from Gibe I Dam. Although there were warnings on the radio, they didn’t reach the Lower Omo; or they were not given value by local authorities. Even if warnings had reached local authorities, they had no means to warn those living in the Omo Delta.

Today, there’s a contingency plan and everybody is ready. Also, I think that there is awareness from the power company to be more careful.

I think the number of casualties was exaggerated. When I returned, I expected a tremendous loss of human life. This didn’t happen. Apparently, there was a breakdown in communication in the media. So, I want to emphasize that on the ground, it wasn’t dramatic as described by the news I heard in Nairobi. I first sent one of my crew, Lale Biwa, to check; and then I checked with my people in the Delta. Nobody could tell about any person they knew that had died, or drowned.

NWNL How do today’s El Nino’s water levels compare to those of 10 years ago?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN The Omo River now is rising beyond imagination. Behind me, the Omo has been flowing so high for many days. I can’t recall having seen such an El Nino year. This is really dramatic.

If we are in an El Nino year, the river will flood for about eighteen months, instead of five months, because it will continue raining through what we call “winter.” Ten years ago it had dramatic effects. The harvest was very poor because even in the highlands people couldn’t plant. So, it was a disastrous year with a breakdown of infrastructure, waterborne diseases, and so on.

For the moment, pastoralists such as the Delta’s Dassanech are comfortable because their cattle can graze in higher grounds, where there is enough grass and the riverbeds still have high-water levels. But some months all that is gone. Grass is gone. Water is gone. Traditionally, the Dassanech then return to this Delta, but now they are confronted with all its islands underwater and inaccessible. The village on a Delta channel where I have my camp will soon be evacuated because of the flooding.

However, such high floods are good for Lake Turkana, because when it rises, areas like Ferguson’s Bay fill up with the water and the fish production increases enormously. So El Nino is positive for the fisherman in Lake Turkana.

Weather and Water

NWNL What local impacts do you see from new monsoonal patterns, movement of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) or climate change? For instance, people said Ethiopia’s terrible 1980’s drought was caused by the ITCZ not moving.

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN I wasn’t here in the 80’s. I came in the 90’s. But I have understood from those involved here in missions or in aid during that drought, that there was more than a problem of drought. There was a problem of distribution priorities.

Ethiopia has always been a great exporter of coffee and agriculture products, and it’s the world’s biggest producer of seeds. In the 80’s, Ethiopia ‘s Communist regime prioritized the efficiency of food production. I think that factor has been underestimated, because since the end of the Derg Regime, Ethiopia’s population has grown. There are fewer problems of food dependency now because farmers are freer to produce. Granted, the Ethiopia’s land issue has not yet been solved; but in practice, people who are on the land utilize it for their benefit.

So, we haven’t seen any repeat of that drought disaster. My guess is the drama was provoked by a combination of weather and the policies of the Emperor and later absolute regimes.

NWNL Since this is such an arid region is water an element in local ceremonies?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN I don’t recall any important ceremony related to “Mother River” – if you would like to call it that. I’ve never witnessed water used for ceremonial purposes probably because, other than the Karo, peoples’ lives are centered around cattle. And even the Karo – the only sedentary people around – have been culturalized by the Hamar; and so their central initiation ceremony is also around cattle. Sometimes, if they don’t have any cattle, they bring them from Hamar communities for their ceremonies.

NWNL But Hamar bull-jumping initiations all begin in the Kesquay River, right?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN That is only with Hamar. The Karo and others have no requirement to jump east of the Kesquay. And for the Hamar, the tradition of location is not so much about the riverbed itself, but to jump east of its banks so that the Hamar living in the mountains far from here don’t need to go further west than the Kesquay River. So, the issue is not the water.

Hamar bull-jumping ceremonies in the Omo Valley allow Hamar men to marry

Solutions to Water Availability

NWNL What can be done to help? Can NGOs or governments bring water to these rural communities?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN For quite some time NGOs, environmental organizations and the Ethiopian government have installed boreholes [wells] and hand pumps to spread out the impacts of grazing in certain areas. They are maybe 10–15 yards [10–15 meters] deep. They do not have to be tremendously deep, as the water table is quite high due to adequate rainfall. They are generally appreciated and utilized, but they are not always successful. Sometimes, the consequence is a proliferation of livestock around the boreholes, adding their burden on certain areas.

Boreholes actually solve little. The main problem – thought of by most as not finding water – is really the need for more grazing surface. Livestock has increased beyond the point that pumps can help. If every cow had to graze within a circle only twenty minutes from a pump, you’d get a depletion of the area around the pump.

NWNL So boreholes are only short-term solutions for the pastoralists?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Yes. When in school in the 1970’s in Europe, I heard about drought in the Saharan countries. It was some of the first televised coverage of such disasters. One of the early solutions deployed by governments and NGOs was to dig boreholes all over the place in the Sahara.

So they built thousands of them. But they only alleviated the situation for several weeks before the livestock grazed itself out too far from the pumps. A cow needs water every 24 hours, so it creates a 24-hour circle of distance in which it can survive. Camels can be without water for 5 days; donkeys 2-1/2 days; goats 36 hours. So a situation develops in which livestock cannot return to water from its grazing area in time to survive.

So, those installed water points didn’t solve the lack of rain and pasture. Livestock still died, because NGOs couldn’t bring the rain needed to revive the pasture.

Efforts by nonprofits to provide wells are appreciated, yet maintenance challenges abound.

NWNL If “the momentary lift” of new boreholes doesn’t help the livestock, does it help people survive the drought?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN These new boreholes actually create problems for the people. As water points were made in all the grazing areas, the pastoralists could spread out, but then were suddenly in conflict with more sedentary people. By definition, there is always a conflict regarding utilization of land resources between farmers and pastoralists. That is playing out now in Niger and Mali. Darfur is the beginning of another situation where pastoralists have ended up in areas of sedentary people.

Boreholes are politically popular. Everybody is in favor of them. The first thing people ask for is a borehole, so women don’t need to walk for water. Around Lake Turkana there are many funds available for boreholes. Now boreholes are all over the place. So now women can go to forested areas that were formerly too far from water. There they cut the trees for charcoal burning, and in so doing create future drought situations.

Also, to put in a borehole, an access road must be made for the drilling machines, which also allows vehicles to come to collect big piles of charcoals. There’s a good example 20 minutes from my camp on Lake Turkana, where the water table will dry up because they are literally cutting all the trees.

Water in the form of rain is one thing. But we should be very careful where and how we make water in the form of boreholes.

NWNL If boreholes cause conflict and deforestation, what alternatives are there?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Now, that is the key question.

NWNL Do the indigenous cultures have any clues to a better solution?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN You should not ideologize indigenous cultures assuming that they have solutions. They expect solutions from us. Very often pastoralists confront me, expecting I will have a solution. When I first came from Kenya they embraced me, thinking I was a kind of savior for their children, for the future, and so on. It took some time to make it clear I’m just a businessman without a solution for everybody.

That is difficult to say. Nobody wants to see somebody dying of thirst. Nobody wants to see livestock die. I’ve been in northern Kenya and the Lower Omo for 25 years and seen many boreholes made. But I haven’t seen those boreholes solving the fundamental problem of pasture. Even in a poor rainy season, boreholes don’t solve problem – they create conflict. So, I have no answer as to what would fundamentally solve of the lack of land resources for an increasing population. This is the fundamental problem we face.

The solution lies in the fact that birth control would stabilize the population, but that is a “no-go.” You cannot talk about anything like family planning. That is culturally taboo.

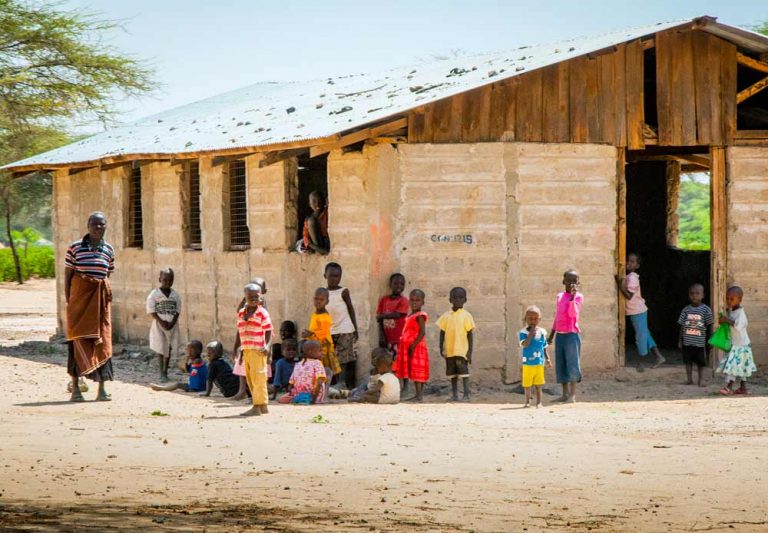

Cohesive families in the Omo Valley follow tribal traditions as they raise children.

NWNL Is there a reason for pastoralists wanting to have lots of children?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Yes. When pastoralists have children, they decide which child will take care of the goats, which one will go to the farm, and which one will do this or that. As more children survive now, they say, “This one will go to school, and this one will take care of….” That creates problems no one anticipated. The ones who take care of the livestock and lead a pastoralist’s life are jealous of the schoolgirl’s easy life.

Having many children is fundamentally important in pastoralists. They will help defend your tribe against raiders. And other disasters can befall a family, like pneumonia. On a night of rain, they run around to save the sheep from pneumonia, and so they catch pneumonia themselves. Those are the realities for pastoralists.

The sedentary Karo form collective farms in those six months when they might run out of food from the previous season, before the river starts receding again so they can plant and harvest. In those tenuous six months, they may have a short period of rain. But such rains are erratic and they don’t always come.

The big problem for all is about enough water for food.

Balancing Nature and Human Needs

NWNL Much of the endemic wildlife here has been hunted to provide food. What are the conflicts today between wildlife and natural watershed elements like riverine forests versus people?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN If the Karo have more mouths to feed, they will create more farms. More farms imply deforestation. They will not deforest the mountains.. Instead, they go to the bend of the river where the water floods. There they cut the native fig trees to decrease the shade, because crops don’t grow well in the shade.

That is happening now. There are dramatic changes in the structure of the bank, because every time the river floods, especially with this force, pieces of fertile land are carried away. But, funny enough, farms don’t disappear. You rarely see the river overtake a farming area where people have crops. So, it’s not as negative as it sounds or looks.

However, by definition, deforestation destroys habitat for birds, tree-climbing colubus and other species in this riverine forest. So the question is whether to preserve wildlife. Although the local people are not aware of that value today, it could have an economic value in the future.

The importance of a camp like this is that the tourism dollars it brings show that forests and wildlife can have an economic value. If the locals cut all the forests, all wildlife will disappear. Birds will disappear. But in terms of food production, it is a necessity for the Karo to cut the trees.

The Trickle of Modern Technology

NWNL Looking at the future, what changes will come into this ancient valley? With you, I’ve witnessed trends towards education, new technologies, new bridges, commercial cotton irrigation schemes…. What will their impacts be?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN In general, rivers in Africa are much less harnessed than elsewhere. They’ve been relatively untouched. The mighty Congo River is still intact. I’ve navigated it two times as a tourist on one of those barges. It was endless, endless, endless untouched forests. Untouched.

It’s felt like the wind of the future is not coming. Even the population impact on African rivers has been relatively mild – but that’s changing. American missionaries have introduced windmills to pump water from the Omo up to crops on the banks when the river is low. But they do not go very fast.

However, the growing populations do present a water concern. As the populations increase, they become more concentrated. People then start defecating around the village. There’s an important village of 10,000 inhabitants on Lake Turkana where everybody “goes to the bush” [defecates outdoors]. The wind and dust that blow there cause eye infections for many people. So they do need water for sanitation.

NWNL It seems there will be many changes and choices for the indigenous people as technology comes to this region.

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Yes. They have to decide between forest or food. I saw the forest along the banks disappear after windmills [installed to pump water up the river banks to irrigate crops] came to Omorate, the Kenya-Ethiopia border town on the Omo. You can’t grow bananas in the shade. But without trees, you can grow bananas plus all those new crops they are bringing – maize and so on.

On the other side, that’s much better than depending on all the relief sent to feed people. And I haven’t seen dramatic changes in the banks. The riverbanks are still the same as they were before the deforestation and windmills. The river moves slowly, so it’s not a very big issue. If the river becomes wider, the land they will irrigate will just move inwards. So I don’t think the river will dry.

We have to weigh the consequence. Of course I would like forest to be intact and not see all those beautiful trees, the colubus, birds and so on disappear. But, then on the other side, the trucks that are coming now with aid and grain and leaving with cotton are not a good alternative.

I look at this from that point of view that people have a right to feed themselves. Installing windmills is a good project overall, but emotionally I have a problem. They are not in my interest. My interest is to have a clean horizon with no modern buildings and everybody in leather or naked.

But I am not arguing. The alternative is wise. It’s a price we have to pay. I know 100,000 years from now the world will be different – perhaps without us. We all die anyway. No Water, No Life.

Windmills built by foreign NGO’s irrigate crops that have replaced stabilizing riverine forests.

The drama of water in the United States is a good example of our need to conserve our resources. On the Colorado and the Mississippi Rivers, every drop is harnessed. The big cities in California suck water from Las Vegas and everywhere. The whole picture includes spraying lawns, filling swimming pools, washing cars…. Here, it’s still natural. And it’s natural that people cut some forest. They also preserve a lot of forest. We are, by the way, replanting trees.

I admire pastoralists, especially from Turkana. They harness nature and survive at the expense of other species, yes. Long-term it’s bad that our children will not experience all of today’s species. But do we have the right to stop it, or stop ourselves from surviving? Is there a religious obligation that we must survive as a species? That’s the most important question I ask myself.

Traditional versus Western Cultures

NWNL It seems to be about that equilibrium of resources and numbers of people.

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Let’s start with ourselves. I believe when you see the CO2footprint of an average Karo and compare the footprint of any Westerner…. Well, let’s not.

Even if the Karo burn a bit of wood, there’s no comparison. There’s at least a thousand-fold difference between Karo and Americans. Three Americans or five Europeans have a bigger CO2footprint than all 600 Karo taken together.

NWNL Will progress for the Omo people affect the quality of the environment? What do we lose when we lose that biodiversity? What do we lose in our knowledge of ethno-botany, medicines, and the symbiosis of the plants and animals?

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Understand that I am in your camp. But I would like to be the advocate of the devil against intellectuals in Africa who want western educations for Kenyans. For example, in discussing conservation versus human life, farms and survival, Kenyans say, “You destroyed all your forests. You made iron in Europe. You completely shaped your landscape. Wildlife has disappeared more or less. Then you went across the big Atlantic and did exactly the same thing, harnessing everything there. Now you feel guilty, so you come to this continent to tell us we cannot follow the same path. That means we have to stay poor; and that we cannot be privileged like you, taking airplanes and such.”

Westerners don’t want Africans to do things that are normal in the Western World. That’s a big problem because African leaders are moving ahead, sometimes out of antagonism and sometimes because we often come in a paternalistic way – advising with good intentions. I know both sides are very well intended, but there are things Westerners and Africans cannot stop.

Nobody wants anybody’s child to die once it’s born. The Karo have a way to control their population that’s effective for them. The Hamar control their population in a way that is relatively democratic but against all laws of Ethiopia. Now people live in harmony. Both tribes have found a way to cope with this harsh environment.

But now, people like Lale Biwa believe that element of control in their culture should be eliminated. When that happens, we really are going to see an explosion in the population.

Of course, we Westerners would say, “What? They live in harmony? They kill their children. They throw them in the river.”

But, I say, for sure, “They have kept themselves in equilibrium with their resources, more or less. But, in the future…?”

Traditional versus Western Solutions

NWNL Yes, the future of the Omo Valley certainly seems to be about that equilibrium of resources and numbers of people.

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN Let’s start with ourselves. I believe when you see the CO2footprint of an average Karo and compare the footprint of any Westerner…. Well, let’s not.

Even if the Karo burn a bit of wood, there’s no comparison. There’s at least a thousand-fold difference between Karo and Americans. Three Americans or five Europeans have a bigger CO2footprint than all 600 Karo taken together.

NWNL Perhaps just one American can have a greater footprint, in some cases.

HALEWIJN SCHEUERMAN We are not dealing with Africans who have learned to think like us. Being well-intentioned, as we were through the ‘80’s and ‘90’s, doesn’t work any more. It doesn’t even work even in terms of conservation. At the end, political leaders are the ones who decide. It’s no longer up to an international body, or colonial power, or so on and so on.

Even money doesn’t talk. I have heard often that money is the solution. Money is not a solution. It’s not about windowpanes for the school or the cleanliness of school classrooms. It’s not about how smart the houses look. It’s about the quality of life.

What I enjoy most is the traditional lifestyle. That’s why I got completely involved in doing the Hamar male bull-jumping initiation. I don’t miss anything being here in the Omo Valley. I don’t miss even my computer or my email. I am trying now to disappear from the modern scene, because the quality of life here is so gratifying and rewarding.

NWNL Would solar energy help address sanitation issues, dubbed WASH by NGOs – and promote better health?

The Omo River – even when muddy during floods – has been a vital resource for 6,000 years.

Posted by NWNL on Aug 27, 2019.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.