Turkana – A Desert Lake Under Threat

Omo River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Omo River Basin

Ikal Angelei

Director of Friends of Lake Turkana

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director and Photographer

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

This interview was conducted in Lodwar, Kenya, concluding an expedition to the western side of Lake Turkana in Kenya’s Northern Frontier District – part of the “Cradle of Mankind” in Africa’s Great Rift Valley. We met Ikal in the office of Friends of Lake Turkana, her stewardship organization. Turkana is the world’s largest desert lake, and in this drought-prone region fishing has been a mainstay of diet and income. Yet, upstream dams in Ethiopia threaten traditional livelihoods around this volcanic Rift Valley lake, often called the Jade Sea. This interview provides critical insights on environmental resource governance, potential transboundary impacts of water control projects and watershed solutions to disruption caused by dams on those living downstream.

Editor’s Update, 2021: Having been awarded the 2012 Goldman Environmental Prize for publicizing the threats of Ethiopia’s Gibe 3 Dam, in 2014 Ikal received the Wetlands International Luc Hoffmann Medal for Excellence in Wetlands Science and Conservation for educating and speaking out for Kenyan indigenous communities threatened by the Gibe Dams. Turkana Basin Institute/TBI Program Coordinator for 12 years and FoLT Director for 10 years, Ikal has a Master’s from SUNY-Stony Brook, and is a PhD Candidate in Geography at the University of Leicester.

NWNL Ikal, I’m so glad to meet in person to discuss the fisheries and other natural values of Lake Turkana and threats to that lake that could so heavily impact the 300,000 residents in its basin. I then want to discuss your dedication to halting construction of Ethiopia’s Gilgel Gibe III Dam on an upstream tributary of the Omo River, source of 90% of Lake Turkana’s volume. So, let’s start with your introducing yourself.

IKAL ANGELEI I’m the Director of Friends of Lake Turkana (FoLT). My work is basically looking at policy issues affecting our natural resources, community rights and environmental justice.

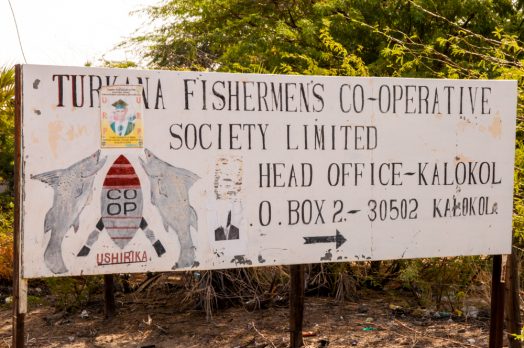

NWNL I’ve reviewed past efforts to monetize the potential of Lake Turkana’s abundant fisheries. Regarding the 1980’s Norwegian fish-processing plant in Kalokol near Ferguson’s Gulf, did it fail due to lack of electricity to keep the fish frozen? Are there lessons to be learned from its failures?

IKAL ANGELEI Lack of electricity was the biggest issue; but also, the local fishermen were excluded from discussions, so there was a lack of skills transfer. The cost of electricity was very high to be able to run such a huge factory. At that time, solar energy was still quite expensive, although it’s become a lot cheaper in recent times.

At the point when the fish processor was set up, many people involved with it were foreigners. When they left – with all their expertise – all that remained was a shell. The Lake Turkana Fishing Cooperative that tried to take over was mainly politically driven, rather than expert-skills driven. Local fishermen. who were supposed to be part of the Cooperative, were not part of this whole process, so the whole thing became a project of the Government of Kenya, using a typical top-down approach, rather than a bottom-up approach to development.

NWNL Would solar energy be a help now?

IKAL ANGELEI Solar is very expensive. One of the things we’re really pushing for now for fish processors is a cash economy.

Lake Turkana needs support for energy production – from biogas to solar to wind. If we join biogas with some parts solar and some parts wind, then we’d have a comprehensive energy production. That’s the only thing to do; because, as of now, getting ice into that place is almost impossible. When people transport fresh fish by truck, the sale price is much lower. But with fresh fish deliveries, they get much more money. Yet transporting fish through the road system that you saw, you have middlemen saying, “Well, to fetch so much money, you have to give us a fee.”

So, it gets harder and harder for fishermen. The fish economy in this area is down and doesn’t really contribute much to our economy. The discussion now is how to support the Lake Turkana fish industry. One argument now is over what this industry really contributes to the economy.

NWNL I’ve heard and seen for myself that there are few Turkana fishing today. I’ve been told that around Eliye Springs, which is near the mouth of the Turkwel River, there are only three or four Turkana who continue to fish.

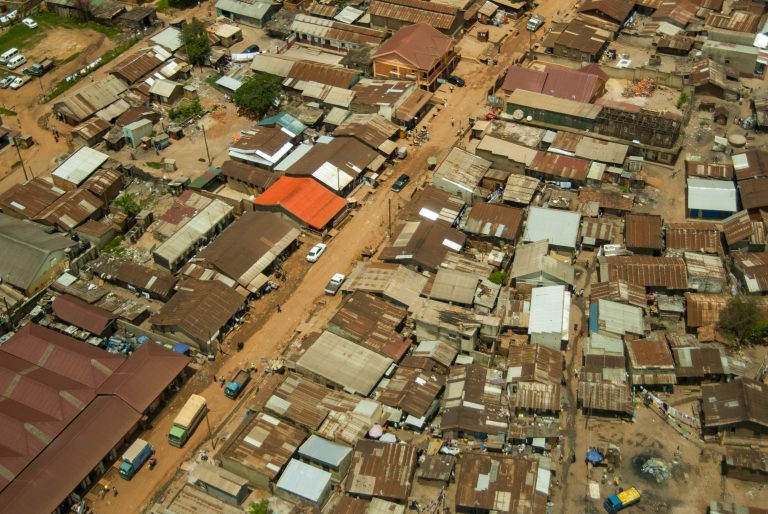

IKAL ANGELEI Yes, around Eliye Springs very few Turkana people still fish. It’s not a fishing village now. It’s more like a resort area. But, if you go 64 km [40 miles] west towards Lodwar (where we are now) and then 40 km [25 mi] north to Kalokol and Ferguson’s Gulf, you’ll find the fishing zone.

NWNL I’ve seen this dramatically remote Northern Frontier District is home to many small and very low-income communities.

IKAL ANGELEI Yes, really very little money is made here in fishing because of transportation costs and marginalization of the region. That’s why there actually hasn’t been a socio-economic costing. It’s very easy for the Government of Kenya to say, “Well, fishing doesn’t have much value in comparison to energy.” Really very little has been done on social and cultural values; but there is economic value in Lake Turkana.

The number of tourists who come here is very low on both sides of the lake since there are few proper roads. Thus, since it’s very expensive to fly here, the economic value of Lake Turkana hasn’t been really captured, and there’s little effort to do so. As my FoLT associate, Billy Caputo noted on how to help the fishermen, it will take an understanding that the numbers of fish have been reduced over time by overpopulation in the area and overfishing on the lake.

NWNL What solutions do you seek to protect the health of the lake and welfare of local people?

IKAL ANGELEI We have to recognize we have an increasing population. Furthermore, climate change has made most people move away from predominant pastoralism around the lake. That has created a cash economy based on fishing. We need support for how we do this sustainably, since overfishing creates an unsustainable resource.

Have you seen how people are fishing the little fish? This destroys the breeding zones in the process. So, threats to our fisheries’ future are man-made, especially when also considering the impacts of Ethiopia’s Gibe 3 Dam in lowering the lake’s water levels. Breeding zones – already shallow by nature – will suffer. We’re trying to adjust. Yes, we can fight to stop Ethiopia’s dams and we can fight to stop new upstream irrigation; but internally what are we doing? We must look at how to protect the breeding zones within the lake.

How do we engage the fishermen to stop them from using protected areas? If we don’t, with the dam completed, in five years we will destroy the breeding zones in Lake Turkana. It will be the same problem we see with logging around the world, where people are cutting trees for charcoal and construction. We’re also dealing with that internal problem – a reality just as big as the dam.

NWNL I’ve talked with scientists in Nairobi who believe these threats are minimal, because there are very deep levels in the lake that fishermen can’t easily access that hold plenty of fish.

IKAL ANGELEI That’s not been evaluated. We’re acting on hypothesis, but we know that in many places in the world with overfishing, once there’s fishing within the breeding zones…

Listen, if we allow fishing in protected areas, in a few years how much do we get out of them? How do we make the lake’s fisheries valuable in terms of income if they sell the little fish? We need to wait and look for quality, for some really good fish that people can profit from.

NWNL You’ve touched on the need for education.

IKAL ANGELEI I think we need to educate people in a way they understand, and not ignore the facts in traditional knowledge of fish in this lake. Most elder fishermen will tell you where they used to fish – where they went for maybe only seven months a year and some places they’d skip for a year. They can tell us how they fished around a certain time, and times of the year they didn’t fish. We need to have those discussions and explain to people what is happening in terms of the size of the fish. We really need to openly engage with them.

NWNL You’ve touched on the need for education.

IKAL ANGELEI I think we need to educate people in a way they understand, and not ignore the facts in traditional knowledge of fish in this lake. Most elder fishermen will tell you where they used to fish – where they went for maybe only seven months a year and some places they’d skip for a year. They can tell us how they fished around a certain time, and times of the year they didn’t fish. We need to have those discussions and explain to people what is happening in terms of the size of the fish. We really need to openly engage with them.

We also must understand it’s going to be really hard, but by using both traditional knowledge and science this discussion will help. We must ask, “How do we balance this? Can we look at a fishing cycle that at times makes so much money, then leave it for some time, and then come back and do it again? But to get to that you have to discuss financial engagement with fishermen. Under such a plan, they’d make a lot of money in two months, but then in the next two months, they couldn’t make the same amount of money and they had squandered their earlier income. It’s a hard topic to discuss with people, because people want results immediately. But that issue must be worked on.

NWNL Let’s get to the big question – the elephant in the room, so to speak. You are greatly concerned about a proposed cascade of five large hydro-dams upstream on Ethiopia’s Gibe River, a tributary to the Omo River that fills 90% of this lake. These dams could impact the levels of Lake Turkana and health of its fisheries. Thus, two years ago you founded Friends of Lake Turkana as a non-governmental organization (NGO) to protect the region’s inhabitants from losses that could occur. Do you think International Rivers, other NGO’s or perhaps the Kenya government can stop Ethiopia from building the Gibe Dams ? Can there be mitigation of water extraction from the Omo River that would irrigate foreign investors’ new cotton and sugar plantations?

IKAL ANGELEI I do have hope that we can have influence. We will not necessarily stop construction of Gibe 3, because it’s 40% done. How can we stop it when funding has already been put into building it? There is hope for that because they’re now hitting on their financing agencies, which right now is only China. But we hope the environmental cost to Kenya will influence our country’s position on this. Kenya’s government has been playing basically Russian roulette – with one ministry saying it’s a bad thing, and another ministry saying Kenya needs its share of the hydro-energy it would provide.

We realize the Gibe Dams’ impacts on Lake Turkana involves geopolitical discussions between Kenya, Ethiopia, and Djibouti regarding oil, energy, agriculture and transport. The Kenya government is basically playing the geo-politics of resources. At first, FoLT thought the dam was the big scare, but I think the irrigation it enables is even worse, because you’re looking at 250,000 to 300,000 new hectares of water-thirsty crops. On top of that, the type of sugar cane they’re planting will use a lot of fertilizer, which then creates phosphates that will flow into Lake Turkana – and its whole basin.

NWNL How do you think the dams’ disruption of water flows will impact downstream tribal, indigenous cultures who’ve been living on the banks of the Omo River and Lake Turkana for 6,000 years and sustaining themselves with traditional flood-recession agriculture?

IKAL ANGELEI The lifestyles Omo tribes have practiced is being destroyed by the dams, just as is the health of Lake Turkana. So, it’s a very, very bad situation. Worst of all, these impacts bring conflict to the whole region. People are already struggling to find resources for survival, and now more pressure put on these communities will be the tipping point.

On the other side, some say, “Well, we’re giving them schools.” But actually, Ethiopia is forcing villages into concentration camps as they take their land. So, it’s really a situation of water privatization, and also land-grabbing; because taking land within a region where people have public access to water means they no longer have access to the water.

The situation is dire; and it’s really scary. But we have to keep pushing on with the struggle. The reason I do a lot of policy work and then come back to communities is that no one has the facts. So, both in the background and through FoLT, I’m looking for ways to influence these policies. The beauty of these discussions is that the Kenyan ministries are engaging now and not just in the typical ministry interests. We’re really pushing and even if we don’t get a full victory, we at least are able to reduce the impact that the dams will have on the communities and the legal system.

NWNL What are the effects of international pressure? There’s been much of that in the last two months, including Sean Avery’s report and National Geographic articles (using some of our No Water No Life photos). What are their impacts and effectiveness?

IKAL ANGELEI I think over time African countries and developing countries are becoming a bit immune to international pressure. It’s not as effective as it used to be. Right now, everyone is looking at Kenya to get reactions, since Ethiopia is totally immune to international pressure.

So, we’re sending these reports to directly to ministries and people in government whom we know have an interest and can influence outcomes, in one way or another. On January 28, we have our first hearing in a court case. We’ll use facts, international pressure and national media to influence local media to feature this story.

NWNL So, the most important role of international media is to affect national media, which then creates a grassroots support?

IKAL ANGELEI Yes, because what happens is national media right now is pressured to follow the elections, so if we then turn it into a story about Kenya in the international media, then they’ll usually focus on it, because right now they’re going with what people want to hear.

NWNL Would you advise NWNL to offer its documentation and images to Kenyan or African media?

IKAL ANGELEI Yes, that would really help highlight the issue. At least it brings the idea closer to home from a different perspective, because other people tell the story in different ways. However, I think international opinion and human rights are irrelevant in Ethiopia, whatever they say.

NWNL What three points that you would like No Water No Life to make?

IKAL ANGELEI Ecological dependence is important. As well, conflict in the region, especially with the oil situation, is the last thing that any community wants to see. Lake Turkana is not just inhabited by the Turkana – it’s home to six ethnic tribes. Actually, non-Turkana tribes have more culture and spiritualist connection to the lake, including hippo songs, crocodile songs and a lot more. So, there are more concerned about that lake than just the Turkana. There’s also a national pride of recognition and identity. People focus on local communities and traditional culture, but there’s a much broader involvement and concern.

NWNL You’ve started from the grassroots, working with the local people. My feeling is that all change has to start at the grassroots. How do you now assess your approach?

IKAL ANGELEI My first month was not about saying the damage would be bad or that our FoLT project was good. It was asking people, “Do you know what is going on?” The biggest value was that although the people didn’t think this threat was serious, they started to engage, remembering the ‘80s when there was a drought and no water came into Lake Turkana. They were able to reflect. It was hard to explain hydrological impacts to our communities, but they could understand the threat of stopping water from flowing from Ethiopia, based on what happened in the 1980’s.

We built on expectations, because they thought, “Well, you’ve come this far on your own, so you should be able to succeed.” Yes, it’s easier to push for policy issues when you know you have a backbone that understands the issues and is willing to struggle on, despite hardships. That’s the biggest value of grassroots efforts.

But also, having people understand in simple terms what destroying the ecosystem means allows us to reflect not just on the enemy outside, but also the enemy within.

NWNL As our organization studies issues in three African and three N American case study watersheds, we are witnessing dam removals in North America. But what’s happening in Africa? It seems more are going up and they’re growing bigger.

IKAL ANGELEI There’s a growing plan this year, especially within the World Bank, to build bigger dams. That’s the idea right now. What’s missing in this new discussion around big dams and climate change discourses promoting a great economy is an open discussion asking, “Why can’t we do a small dam?” or “Why can’t we do a runoff dam?” or “Why do we need a huge dam and grand infrastructure?

Yes, there are some places that need grand infrastructure, but there are places where small infrastructure actually impacts lives in positive ways. That’s really where we in Africa want this discussion to go.

NWNL Yes, I’ve documented the value of small hydro projects, even mini-hydro projects, that work well in N America as well as Africa.

IKAL ANGELEI The biggest dams now exist because China supports large dams. They have them in every possible water system in their country. So now they’re bringing dams to the Amazon, Russia, and all over the world in order to keep their companies relevant.

NWNL I’ll always remember when International Rivers sent me news that the European Investment Bank (EIB), African Development Bank (AfDB) and others had cancelled their financing for Ethiopia’s Gibe 3 Dam. Then, a week or ten days later, the celebration ended as China stepped in to fund and construct those dams.

IKAL ANGELEI We don’t know how to deal now with China, and so we’re trying everything. FoLT is going to try a template on our website so people can write letters online. And we’ll send packages and letters to ICBC [Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, lender of $240 million for Gibe 3 construction] just to keep pushing our message. At the same time, I hope to go to China for a meeting there and to meet with a Chinese ambassador here.

NWNL Have you met him already?

IKAL ANGELEI Yes. He was nice at first, but the Chinese argument keeps going back to “Kenya wants this.” We not only have to approach politicians, ministers and cabinet secretaries; but to effect change experts need to start meeting with the Ministry of Environment. We hope courts will rule that Kenya has to pull out, so then we can tell China, “Our courts have said Kenya did not follow required procedures when signing the agreement.”

I think China’s interest, actually, is in fueling wars in this part of East Africa, as it’s a very unstable region. China has to see that they’re no longer only dealing with governments – they’re also dealing with people. They need to responsibly investment in the country, not just in its governments.

NWNL Certainly, people are starting to realize and limit China’s poaching and development in Africa. Yet poaching by the Chinese is getting worse. I wonder if one effect of Kenya’s recent election could be a turning point that allows you and others to muster more power against China.

IKAL ANGELEI Right now, we hope the new Constitution gives us room and space to adjust with issues. Before, we had politicians as ministers, but now we’ll have non-political experts on the job. So now it may be a geopolitical discussion, but at least they’ll be more influenced by expertise. Experts will base their work on rulings, rather than political affiliations or cronies.

NWNL The subject of experts brings me back to the Leakeys’ Turkana Basin Institute/TB, located here, near Lodwar. What is their focus, and what role might they play in your effort – or how best could they support you?

IKAL ANGELEI TBI facilitates research in the Lake Turkana Basin, focusing on anthropology, paleontology, hydrology and science. They study how past and present science affects humanity and the way the world works. The Institute has been critically helpful and keen for us to use their support as we look at geology, hydrogeology, chemistry, fish studies and all that.

We use TBI to understand where we are now and how pressures from the Gibe Dams and oil exploration can affect our local populations and environment. However, theirs is a very academic position which we then have to break down in many cases to influence policy, discuss and inform debate regarding Lake Turkana.

NWNL Does TBI include local Kenyans, or are its members just from the US and Europe?

IKAL ANGELEI Right now their individual researchers have worked in this region for a very long time. There is some work that comes from outside Kenya, so TBI uses students studying in Kenya or abroad, and students in the Kenyan Marine Fisheries Research Institute. Much of TBI’s work is funded for particular projects, so there’s very little support to provide local knowledge or local expertise, which can be a problem for us.

NWNL What is on your agenda for the immediate future?

IKAL ANGELEI I’m going to Uganda on Wednesday, since there is very little expertise in that country around the current oil exploration on the lake. If oil is discovered, it’s definitely going to be almost impossible to say, “Do not extract the oil.” We’ll have to deal with that and with managing expectations, because out of all the companies, the one there now has shown how much money they have.

IKAL ANGELEI It’s hard to discuss how I’ll do this or that. I used to say I’m all about finding community support. But I’m going to Oregon in February to learn more about environmental law and using lawyers and scientists in different fields for assessments and as global support partners. I hope to learn to better decipher law, because it’s very scientific, very academic. I’ll also be part of a session where I’m going to explain the issues and the challenges we have here.

We hope we’ll get support from there around environmental issues, exploration, and not just oil, but oil, gas, and other minerals. Everyone’s discussing environmental issues, exploration, oil, gas, and minerals – but there are really no action points. We must understand that the oil companies have and use this information – but neither our governments nor our communities have that knowledge. So, there’s a big gap in day-to-day work needed to support environmental processes. These are discussions I wish we could have more often in Kenya. We all complain about problems, but how can we address small solutions and also influence the big picture?

In the last few years, I’ve tried to address the small picture, but over time I’ve realized issues around this country are big. They are both political and about policy, as well as being societal. Here we’re struggling with Lake Turkana. In Uganda they’re struggling with Lake Victoria. It’s time we start looking at one-world policy and actions. We need to focus on who to hold responsible. We keep fighting fires, but we can only do that for so long. It’s time to heal on a local level, but we must also work from a larger policy level.

NWNL How would you advise those wanting to support Ethiopia’s indigenous Omo River tribes now being displaced as international investors are given their traditional lands along the Omo River?

IKAL ANGELEI My thought regarding the Omo Basin is to openly discuss what’s happening to help them face the reality that they need to invest in education. Until the people from the Omo tribes go to school and start fighting for themselves, no one else is going to fight for them and they’ll be wiped out as they are based in concentration camps by the government.

NWNL What about the large dams Ethiopia is proposing for the Nile River Basin?

IKAL ANGELEI I did get involved in the Nile Basin. It is really frustrating. Too much money was pumped into the old Nile Basin Initiative, and yet no one wants to look at that data. I asked for their data, when doing my thesis on various case studies on hydro-politics in Mexico, the U.S., and Canada. I then studied the Nile and the Omo Basins. I learned that in the Nile Basin they completely ignored data on numbers of people and how much water was being used.

NWNL There was a big article that came out about a week ago on Ethiopia’s plans for its Great Renaissance Dam.

IKAL ANGELEI Yes, allowing Ethiopia to put two huge dams on the Nile is another time bomb that will explode at some point. I know people in Ethiopia are getting released out of jail if they give their earnings to the Great Renaissance Dam. Ethiopia needs every penny to build this dam. My opinion is that Egypt has enjoyed plenty of water for a long time; but doesn’t mean that we have to crucify them now, as they face impacts of this new dam.

NWNL Ikal, your stewardship efforts are impressive and worthy of the global attention they have garnered. Thank you for sharing all your insights, concerns and the solutions you are studying. I have great appreciation for your energy and your work.

IKAL ANGELEI Thank you. I too follow your work, and I have done so even before you got in touch with me.

Posted by NWNL on January 21, 2021.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.