The Whole River Through Time

Columbia River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Columbia River Basin

William D. Layman

Researcher, Author and Photo-historian

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director and Photographer

As a self-described “site guardian,” Bill Layman has compressed many Columbia River stories into two books that should be read by anyone interested in past, present and future challenges to our rivers. As one reviewer noted, Bill’s books offer an “immersion” into the transboundary and geologic importance of the Columbia River and its salmon. Bill’s close rapport with many Native Americans in the Columbia Basin can inspire all of us to better protect our rivers and become wiser stewards.

• River of Memory: The Everlasting Columbia (Wenatchee WA: Wenatchee Valley Museum and Cultural Center, 2006).

A COLUMBIA LEGACY of DOCUMENTATION

MIGRATORY FISH STOPPED – OH, DAM!

BALANCING OPPOSING NEEDS

POLLUTION from MOUNTAINS to OCEAN

NUCLEAR POLLUTION

THE WANAPUM, DAMS & HANFORD

A CEREMONY OF TEARS

ORAL TRADITIONS & MYTHS

EXCERPT from BILL’s “NATIVE RIVER”

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

NWNL Bill, what inspired you to delve so deeply into the myths and realities of this grand Columbia River Basin?

BILL LAYMAN There’s been an outpouring of interest and work trying to document and understand the Columbia River. My favorite book on this amazing river is M. J. Lorraine’s The Columbia Unveiled: Being the Story of a Trip, Alone, in a Rowboat from the Source to the Mouth of the Columbia (1924) Lorraine was an adventurer, who at age 65 built his own rowboat to go downriver. He disdained anybody who thought that someone at 65 couldn’t do this. His book, written from the perspective of a whitewater river rafter, attests to his being a great storyteller.

NWNL An amazing roster of explorers have followed this river – from David Thompson, an Anglo-Canadian fur trader and cartographer in 1811, to Chris Wayne who swam the entire river in 2006. I’m humbled to follow the great Columbia heroes!

BILL LAYMAN Well, my latest lecture, “Developing the whole river and understanding it through time,” chronicles people interested in this cold river through the ages – including missionaries, explorers, government representatives, adventure travelers and more. Today Columbia Riverkeepers is networking with all the small local groups in this watershed.

We had a Rendezvous here last year when our Columbia River Exhibit opened in Wenatchee. There were groups from both the source and the mouth of the river. That helped spur talk about our separate issues. We decided to support each other by developing a sense of a whole river consciousness. It was just wonderful.

Some of us from Wenatchee to Astoria are now writing letters about proposed LNG terminals in the mouth of the Columbia. Our all-in understanding acknowledges that we all live downstream from somewhere. What one does in river activism in one place supports what another person might do in another section of river.

NWNL No Water No Life has a similar “upstream-downstream” focus that serves as our formula for watershed cohesion. We hope our methodology and photography directed to documenting watersheds will help coalesce groups upstream and downstream, state to state and continent to continent. We strongly support partnership.

Bill, part of your legacy in the Columbia Basin is your many images that contrast today’s river, full of modern infrastructure, against images from earlier times that focused on the river’s grandeur. Your photos of rivers in today’s Anthropocene Age create a shock when juxtaposed against early photos of pristine waterways that deeply awed early explorers and Native Tribes.

BILL LAYMAN And you are standing on the shoulders of a huge photographic tradition and body of work that continues to evolve.

NWNL Yes, it’s important to pay attention to evolving priorities and interests. I spoke with a pulp mill worker in Canada who said, “Yeah, we’ve pushed our company to make some changes.” A fish biologist told me, “You know, it used to be that working for your employer was your life. But now, as employees we’re likely to say, “I know my science. That comes before my being a company employee.” In Trail, BC, a Teck Cominco communications employee noted, “I care about this river. That’s my priority. My children swim in this river.” These commitments to clean water are refreshing.

NWNL Bill, you live about halfway down the Columbia. Fortunately for you, you’re not at the estuary, because then I’d have twice as many questions for you. Thus far, everyone has answered my questions with, “Bill Layman can tell you….” So, let’s talk about water used for irrigation in this dry land.

BILL LAYMAN Well, the Columbia Basin’s irrigation project is run with all the precision and choreography needed for operating the entire river system, from Mica Dam to Portland’s hydro facilities. Grand Coulee provides a huge uptake of water, since it was meant for irrigation. Thus, the Bureau of Reclamation has management authority there.

The Columbia is a story about what happens to the water. Fortunately, much of the irrigation water goes back into the Columbia River downstream, via Crab Creek and other channels for water, not used for irrigation.

NWNL Yet many here feel we should focus more on the impacts of over-extraction from the river. Water channelized away from the river is potentially very critical to the river’s health; and there are the dams.

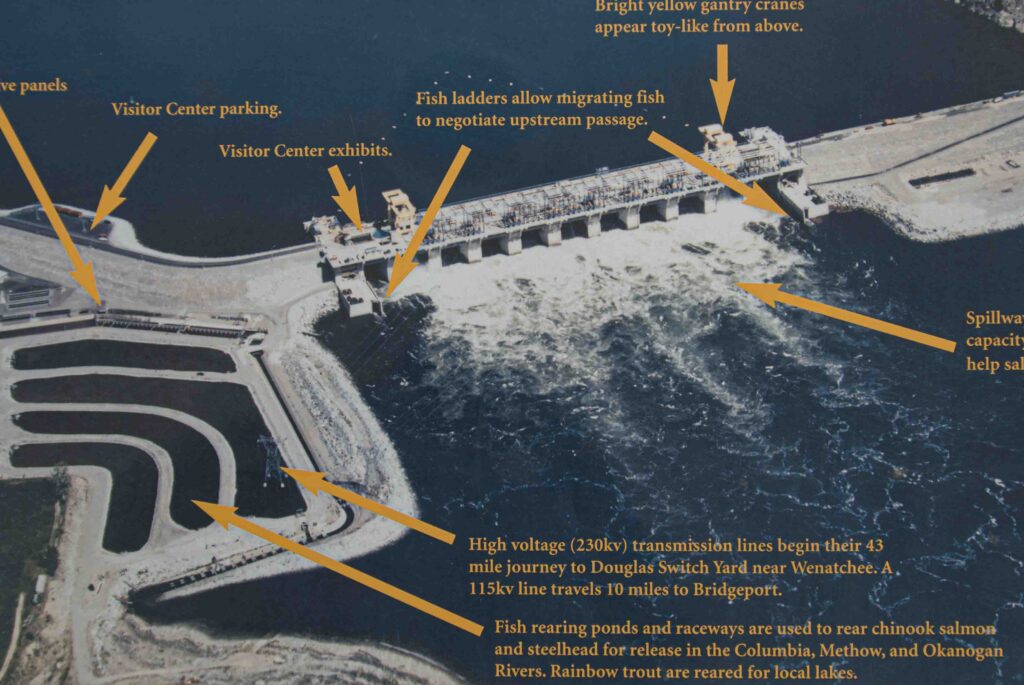

NWNL I hear the Public Utility Districts [PUDs] supplement what the government wouldn’t do to improve Columbia River dams, including installing fish ladders to address dams blocking fish migrations.

BILL LAYMAN Well, that’s more for dams like Rock Island and Wells Dam. There’s a very, very sad story from 1941 when the fish migration first came up the river after dams closed their passage. The salmon migration instinct is so strong that when they first arrived at the dam, they just kept hitting their heads against the dam wall. The Indian people that I know who saw that were grief-stricken.

Regarding fish ladder technology to help salmon moving upstream past a dam, you should know that is relatively easy, compared to helping newly born salmon “fry” struggling to come downstream. That’s where the real challenge is. First, the fry must deal with the new lakes’ increased water temperatures that their bodies aren’t designed to address. Also, the fry are on a very tight time schedule to get to the ocean. Now, they must swim through all the slack water backed up behind dams in reservoirs, such Lake Roosevelt. So, now they can’t make that downstream journey in 20 or 25 days from Revelstoke or Golden, as they once did. One big challenge is how to get the fry and juvenile salmon to the ocean in what was normal time.

NWNL I’ve heard some dams – I think Wells Dam is one – increase their water releases at that time to help increase their passage time.

BILL LAYMAN Yes, all the dams are mandated to do that. It’s a big issue. But just last week, BPA [Bonneville Power Administration] decided not to do some of those planned spills, because they wanted energy for the grid. The river’s balance has shifted toward power generation and against downstream migrations.

NWNL The crux of today’s issues in the Columbia Basin clearly seems to be our demand for energy versus the health of the river and its salmon. Yet, unless you’re from the Pacific Northwest, it’s hard to understand the importance of salmon. It was a learning curve for me, as an Easterner. My awakening came when I read that tree rings are thicker on years of heavy salmon runs. I then realized salmon are not just an iconic, spiritual or publicity token. They nourish the entire Northwest environment.

So how do you see the balance in energy needs versus health of the river, salmon, and the environment? I was told this week, “The balance is in the public eye.”

BILL LAYMAN The balance is more complicated than that. Recreational needs, barge transportation needs, sports fishermen’s needs, industrial needs…. The list goes on and on. So how do we bring them together? Imagine a circle with 25 people, all with rifles pointing across at another person, saying “You’re the reason I’m having problems.” That dialogue points to why the blame is your fault. But the issues are more sophisticated than that and so very, very complex.

At the bottom of it, different values govern decisions that have become very complex. If we take this away or give that to the river, we un-balance the most heavily managed river system on the planet. Changing the balance gets more and more difficult. For instance, how many fish can indigenous people take from the river versus sports fishermen? It takes a major decision to alter that balance at this point.

NWNL Where is balance going in the future, given today’s conflicts between energy needs, irrigation needs and health needs of the river as a whole?

BILL LAYMAN Well, I’m primarily a photo-historian, so my clarity of each complex issue is limited through that lens.

NWNL I can understand that your lens is often “fogged” by the complexity of many issues in this river basin. So, let’s start with the clarity of the water itself.

NWNL How do you assess what should be clean water in the Columbia and its tributaries?

BILL LAYMAN I know it matters what we put into our soils. It matters whether we have living soils or sterile soils with phosphate fertilizers that end up in our river. Issues that we were never aware of before are now critical. How many Prozac pills have been thrown down our toilets – or antidepressants and other pharmaceuticals. And where do they go? The river begins at the end of your faucet. We have a river filled with very, very powerful medications from pharmaceuticals, as well as flame retardants we dumped from the air to suppress forest fires. They all accumulate in the river.

NWNL And they accumulate beyond the river according to your wife Susan, who spoke about the two “dead zones” beyond the mouth of the Columbia,.

BILL LAYMAN Yes. I’ve not read papers on that, but I’ve heard time and time again there are two dead zones. Prior to Grand Coulee Dam, the Columbia River’s plume extended 600 miles out into the ocean, depending upon the season. So, we must think where does a river end? Most of us think rivers end at the mouth of the river, but they don’t end there. The map in our exhibit shows the that plumes circa 1950 – after Grand Coulee Dam, but before the Snake River Dams – extended down to California. So, even salmon that come down from Alaska catch that trace of Columbia River water in the ocean, which they can follow into the mouth of the river and continue on upriver to their shallow spawning streams.

So, we must think of the river as extending beyond its mouth. And we must be conscious that the river remembers everything we do to it and put into it – good and bad. During floods, it is the recipient of all our industrial waste and of all the sewage, especially from Portland. The river, even at its mouth, sadly still contains raw sewage.

NWNL Your photo exhibit at Touchstone Museum in Nelson noted that the Columbia River plume supplies the largest amount of water into the Pacific Ocean. Does that include water from Asia and the Pacific Rim?

BILL LAYMAN The statistic is that before hydro-dams, 90% percent of fresh water in the Pacific Ocean between Puget Sound and Sacramento River came from the Columbia.

NWNL In addition to pollution, dams stopping salmon migrations means they can no longer spawn upstream and thus leave behind their nutrient-rich carcasses to enrich those tributaries’ soil, trees, bear and other vegetation and wildlife. So, if the river lacks those nutrients, future salmon won’t sense tannins from the forest that have directed their migrations. This river – that was full of salmon and wood from forests – is today full of loss.

BILL LAYMAN Yes, those nutrients and tannins are part of the Columbia’s great story of wood and salmon. Many people made their living on capturing logs that came downriver. The Priest Rapids Indians would capture logs to build their structures, since there weren’t many local trees.

NWNL Your exhibit also conveyed the need to constantly assess our feelings about the Columbia River’s values and threats. That gets back to my question of how to balance the issues facing the Columbia. What are we doing today that we may look back at in 30 or 100 years from now that would lead us to ask, ‘Why didn’t we see those great threats? Bill, what do you see today as the greatest threats?

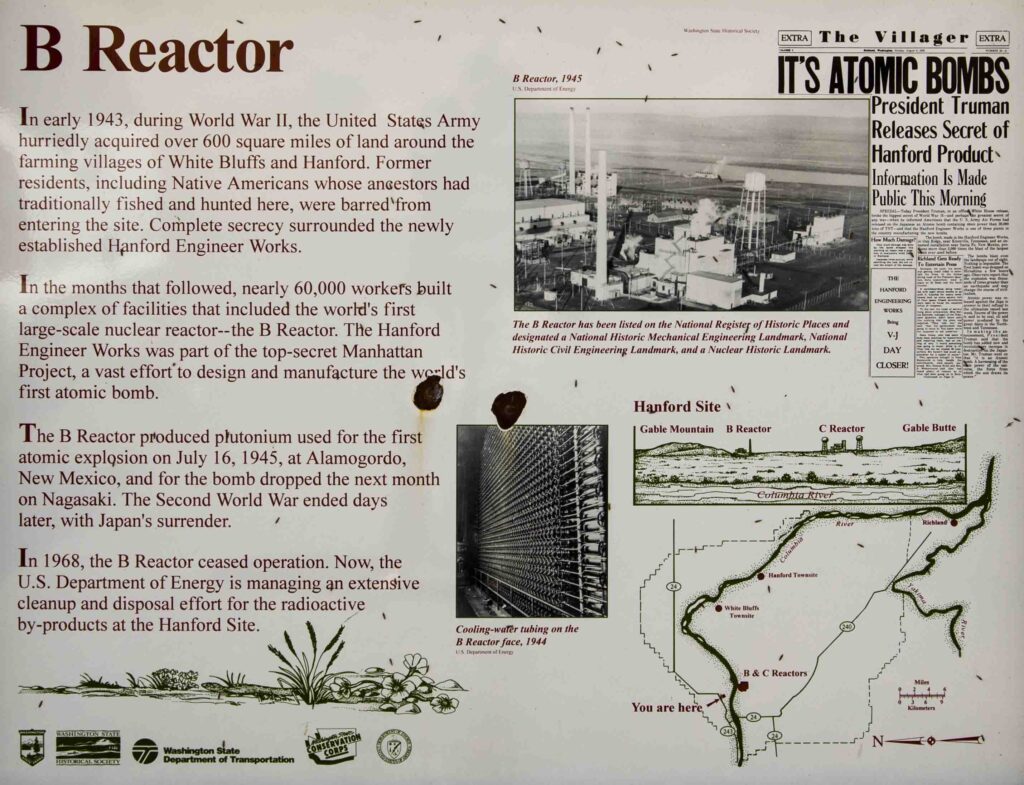

BILL LAYMAN The worst threats are radioactive plumes reaching our groundwater and then flowing into the river.

NWNL Bill, what possessed us to allow Hanford Nuclear Site’s nuclear pollution to spill into groundwater and the Columbia River? Two million people live downstream from there, including those living in the city of Portland!

BILL LAYMAN Good question! What possessed us in the 1960’s to discharge hot water from Hanford’s nuclear reactors into our river when it is is an essential resource for our crops, food and drinking water? We’ve spewed highly radioactive water directly into the Columbia River! Sadly, that water even went into our babies’ cribs.

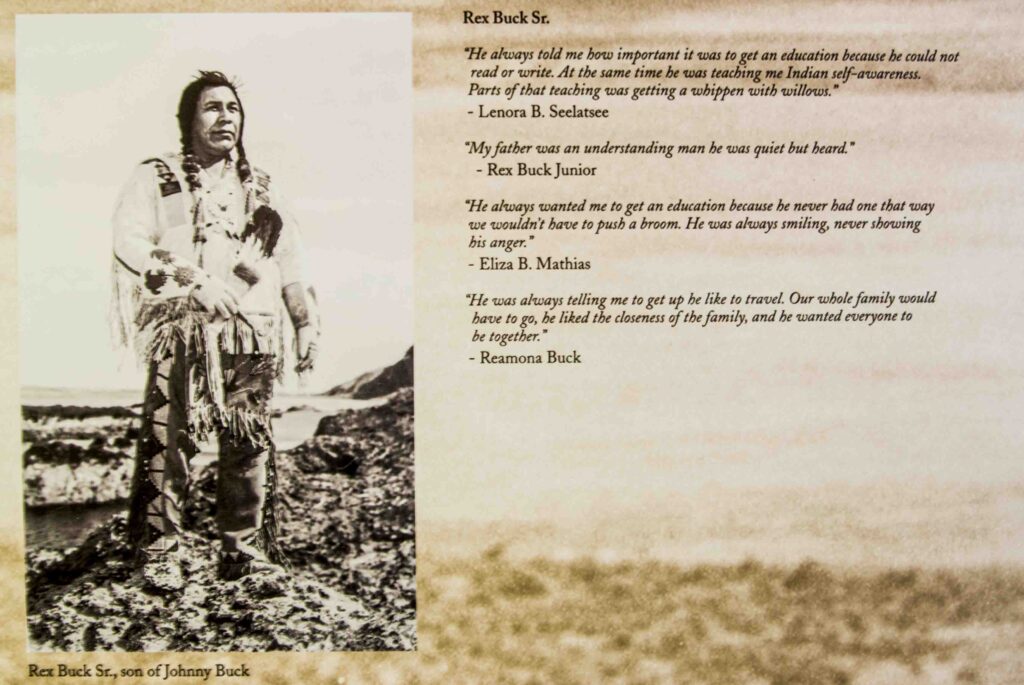

You’re right to ask, “What were we thinking?” I hope you’ll talk to people in Richland about Hanford Nuclear Center, especially Rex Buck, Jr. of the Wanapum Nation.

NWNL Yes, I plan to meet Rex in Richland on Monday, plus Gerry Pollet (from Heart of America Northwest) and Greg Hughes (of US Fish and Wildlife in Richmond WA).

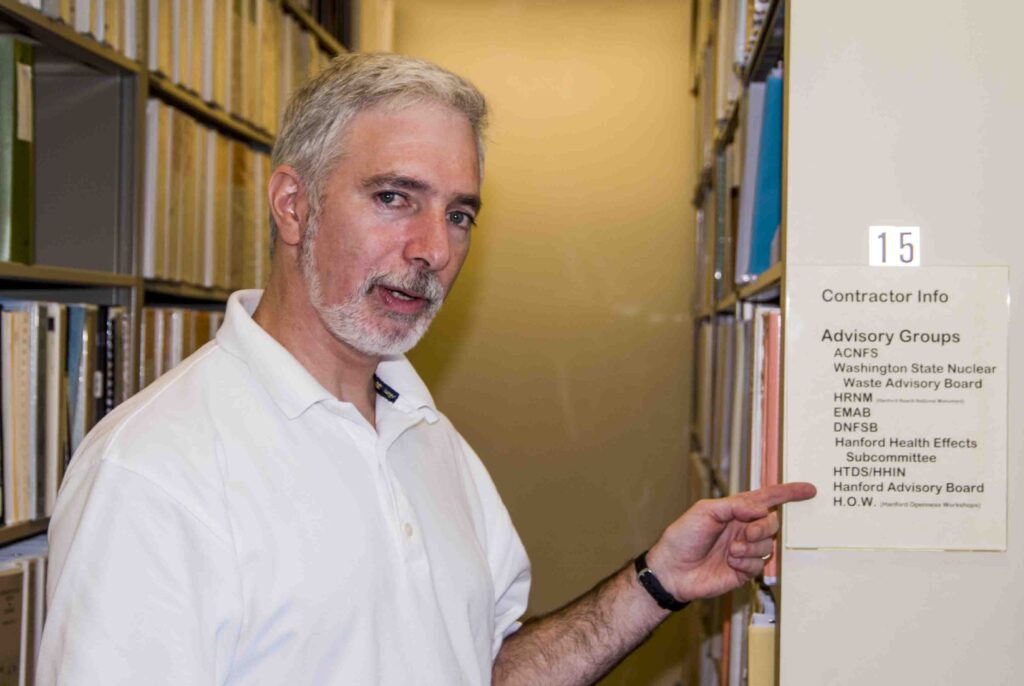

BILL LAYMAN Rex is an amazing person. If you meet one person in your river journey, I recommend it be Rex. I’m a very fortunate man to have Rex as a spiritual teacher. As well, Michelle Gerber is THE Hanford historian. She’s essentially the one who, through the Freedom of Information Act, got semi-truck loads of previously classified materials driven to her doorstep. She poured over them and pieced together the largely untold story of Hanford.

Perhaps you can also visit Wanapum Village by driving across the Wanapum Dam — but to do so you must have business with the Wanapums. For 20-25 years, I’ve visited their sweat lodge every other month. [EDITOR’S NOTE: Unfortunately, NWNL did not meet, with Rex Buck as planned, due to the death of his sister; but we spoke briefly by phone.]

NWNL Gerry Pollet, with Heart of America Northwest in Seattle, studies ongoing environmental threats from Hanford Nuclear Site. We’ll meet at the Hanford Library that holds Hanford’s history. I suspect that library will not be as comforting as your library here!

BILL LAYMAN Gerry’s Heart of America Northwest is amazing. The group that preceded them [HEAL/Hanford Education Action League] was the primary citizen-action group that brought this story to light.

NWNL I hear our Administration is thinking of sending more nuclear waste to Hanford, despite the documented leaks there.

BILL LAYMAN Well, I think Gerry will tell you that the U.S. has 37 million gallons of nuclear waste we’ve not yet dealt with. So, yes, Hanford’s site may be chosen from the eleven that are being considered by GNEP. [The Global Nuclear Energy Partnership that promotes greater energy security.]

They call it “recycling” which, of course, is reprocessing. They want to bring 60,000 metric tons of nuclear fuel rods into the chosen facility. The government‘s bottom line is to keep open the possibility of making bombs from this waste. Hanford is high on their list for that site because it has a long tradition of making bombs from nuclear materials. It’s quite frightening.

NWNL Just below the Canadian border, I happened to see the scar of the Midnight Mine above the Spokane River. The owner of my motel near Fruitland told me that 5 or 6 years ago, about 20 scientists came from Washington D.C. for a month to take daily water samples. They said that raw mining scar wouldn’t become a Superfund Site, because a cleanup of its uranium would cost more than that of 5 or 6 other cleanups combined!

BILL LAYMAN Indeed, the Spokane River has a huge legacy of pollution.

NWNL I hear Coeur d’Alene Basin has some of the biggest Superfund cleanups. So many pollutants were put into this river!

BILL LAYMAN Well, if you are serious about understanding the Columbia River, you’d better be serious about confronting your own capacity to grieve, because there are so many different levels of grief. Just the displacements alone …

Talk to early residents of White Bluffs and Hanford who had to leave their orchards and little farming communities on the river that they loved. People in White Bluffs got what they called “Black Letters.” Some were told to move in 48 hours, others in 30 days – with no explanation of why. It just was “in the national interest.” There was no mention of a “nuclear reservation.” They just had to move. So, everybody packed their belongings and met in the town square, asking each other:

“Where will you go?” “Well, where are you going?”

“I don’t know.” “Where are you going?”

“Well, we are going here.…”

They just had to leave.

That displacement sadly echoes the displacement of Native American tribes and First Nation tribes up and down the river as treaties and Presidential Orders forced them off their traditional lands. As well, when the Columbia River Dam Treaty came about, residents of Arrow Lakes were displaced – and so were the fish!

So, the Columbia story is a story of displacement. It is like what we call “nature deficit disorder” in that we are “un-placed” when we are displaced from the river. Today’s river isn’t the river we lived with 200 or 300 years ago.

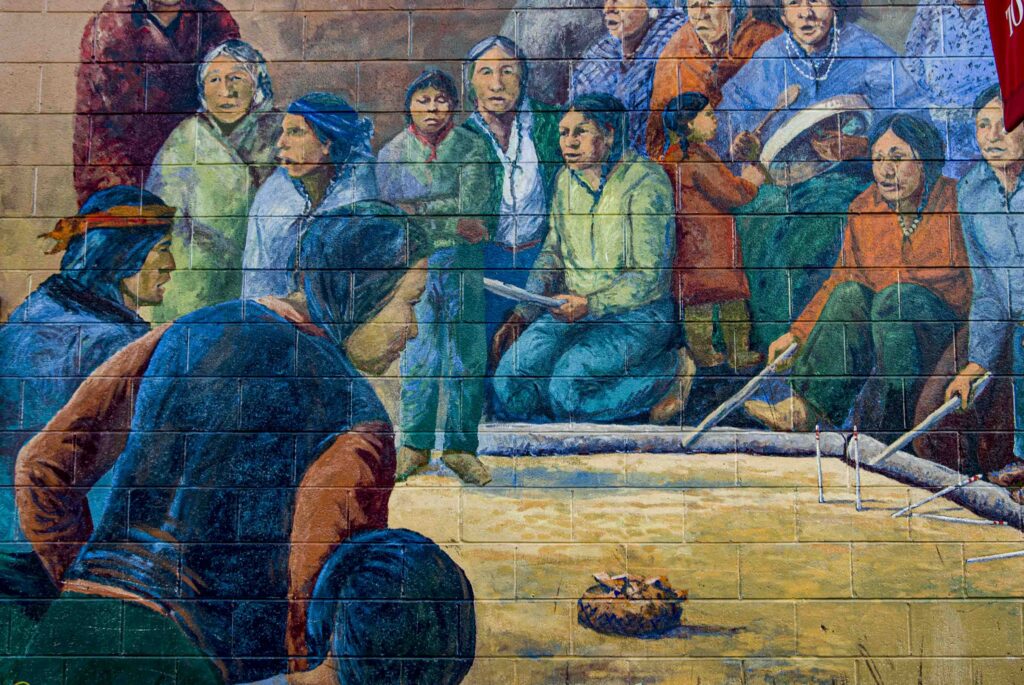

NWNL In this story of displacement, there was a Ceremony of Tears when the dam reservoirs were filled, flooding tribal lands and settlements. For instance, the Colville Federated Tribes were told to move away from Kettle Falls.

BILL LAYMAN To have remembered Kettle Falls, you’d need to be in your nineties. I was part of a theatre group that went to Kettle Falls to invite community elders to share their stories. We then enacted those stories using a format called Playback Theatre. It was a very, very moving night. Many of us were in tears.

We all loved Kettle Falls. Next to Celilo Falls, it was probably the second greatest inland fishery on the continent — maybe in the world. Traditionally, tribes from all over the Pacific Northwest came annually to procure their season’s supply of salmon. The diet of those indigenous people was probably 60% percent reliant on salmon.

The beauty of Kettle Falls is that so many people came to this cooperative fishery. At Celilo Falls [in the Lower Columbia now taken over by the Dalles Dam], individual families and groups owned their fishing stations. There were very strict protocols related to who could fish at a given place. Because the nature of its falls, Kettle Falls was organized and maintained by the Salmon Chief who made all decisions. There were no individual or tribal fishing stations. Most of the fish were caught by great big “J baskets” put at the lower falls, where they’d catch 50 fish at a time. Those catches would be shared evenly among all the people. No one would go hungry.

Cooperation at that fishery was extreme. It’s difficult to imagine a place that is your life cord – the heartbeat of your ancestral sustenance and nourishment – could suddenly disappear, as Kettle Falls did on July 12, 1941. Some with lands flooded by Grand Coulee Dam died of heartache, just from that.

The Ceremony of Tears was held at Kettle Falls, the burial grounds of their Ancestors and where marriages were made. It was where the social fabric of the Inland Plateau Culture Area was held together. Having that place disappear was like losing the center of one’s being.

From time immemorial, indigenous people have had various rituals and ceremonies to mark important times. In that tradition, the Ceremony of Tears was a grieving ritual, lasting about a week. I’ve read newspaper accounts of it and other reports. Much of what happened there was kept within oral tradition, not written. Everyone felt the grief of that loss that week.

NWNL Bill, as a historian, do you know of any similar situation of a large culture, like that of these Plateau Indians, bound by a single place, like Kettle Falls?

BILL LAYMAN Well, the French told the Polynesian Islanders to vacate before blasting their nuclear bomb. Perhaps that had that same the same effect. But a river system is different from an island system. Any similar site would have to be a river-reliant culture. For instance, different from salmon, Plains bison didn’t migrate yearly to one central place where Native Americans could gather to easily hunt them and thus nourish their culture.

Kettle Falls, however, was a place of sustenance where salmon migrated seasonally in reliably great numbers. The Frazier, Copper and Yukon Rivers are also large rivers, and thus home to anadromous fish. They too have places where people congregated to fish. But the Columbia is particularly outstanding in that aspect. Many rivers have fisheries up and down the river; but the great fisheries at Kettle Falls, Celilo Falls (known now as the Dalles) and The Cascades were unique places where it was very easy to procure great numbers of fish.

NWNL Also, do you know of any species that has played such a critical keystone role in their environment as salmon have?

BILL LAYMAN No. certainly not in this watershed. Hey, what other species provide 60% of your diet?

However, bison were very integral to the huge population of Plains Indians. Bison certainly impacted the character of their land, even in how their hooves didn’t hurt the land, unlike cattle. So, bison, like salmon were key to their environment.

NWNL Your Touchstone exhibit in Nelson, British Columbia, highlighted a water monster, a being from ancient time. It lurked beneath the river’s whirlpools and rapids. swallowing the animal people who preceded humans. There must be many other such tales….

BILL LAYMAN Yes, there’s a huge body of oral tradition, and now written myths, of the Columbia River. They tell how salmon people came up the river, how the salmon came, how the river was made, and many different events. With an indigenous world view and a deeply embedded familiarity of place, every rock and every landform become characters in a story that becomes myth over time. They help make sense of those places and teach how to care for the salmon and to be careful around certain places, such as whirlpools, rapids or dangerous places where people fish and do other things. Such stories help make sense when people would misstep and fall in the river.

It is said that the Columbia never gives up its dead. Pioneer accounts say that if you get caught in a whirlpool or drown in the river, your body perhaps will not resurface for a long time, because there are drops in the river that keep you pinned down. Even a 200-foot cedar tree pulled down in a whirlpool can then pop out 2 miles downriver. So perhaps a water monster could take a body or even swallow an unfortunate person who mis-stepped along the riverbank. You don’t see him, but you know he is lurking there. They say that whirlpools have jaws that open and close like a big monster.

NWNL I thought perhaps the water monster was modeled on the great white sturgeon in the Columbia, since they can be up to 20 feet long. Such a fish could seem like a water monster.

BILL LAYMAN Well, in one tribal language, “white sturgeon” is wonderfully translated as “the pet of the water monster.”

NWNL That makes the water monster a lot bigger. What a great perspective!

BILL LAYMAN I think knowledge from books can diminish the true source of knowledge already written in the heart of the people.

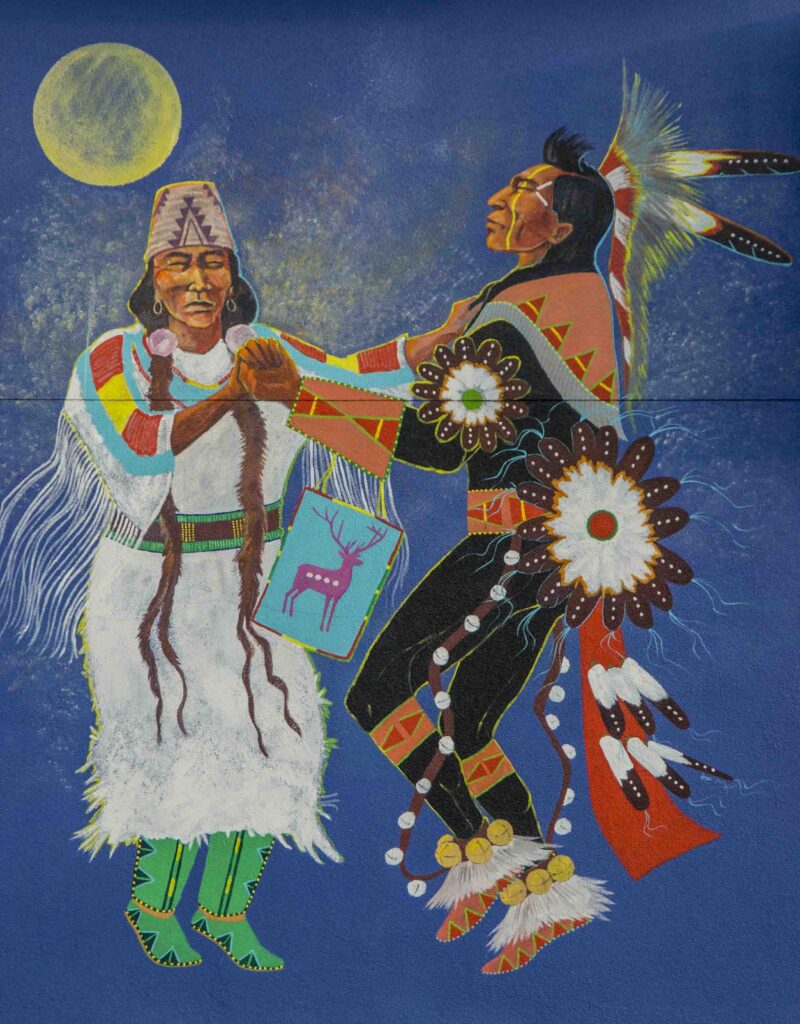

NWNL Perhaps that’s the difference between oral tradition and written tradition. It seems myths reveal a bottom-up social structure where one shares traditions, dance and song.

BILL LAYMAN Yes, myths represent a mutual intelligence held by all. With myths, everyone knows how to act and behave. That dialectic between oral and written tradition has a tension. Oral traditions are people’s concerns about the future and ensuring that their knowledge be passed on. We’ve worked to put their languages into a written form. The Salish people in the Okanagan Nation Alliance have a great language program now, as do some other tribes.

NWNL I heard the word “dalles” means “rapids.” Is that a tribal word?

BILL LAYMAN No, it’s a French word, used at 4 or 5 places in the Columbia Basin, including “The Dalles” at Celilo, “Little Dalles” above Revelstoke, and “The Dalles Oregon” which is not really a rapid. Another “Little Dalles” is below the border. In my book, River of Memory, I describe how “Little Dalles” is a narrowing of the river with many whirlpools.

NWNL Back to Native American languages, I talked to Deana Machin, a fisheries manager of the Okanagan National Alliance. She grew up off the reservation and truly regrets she can’t speak the Okanagan language. But her children are now learning it.

BILL LAYMAN Their young do a salmon dance, as a part of an event called “Honoring the Elders”. One day we closed our Touchstone Museum exhibit to all but Columbia River elders. People came down from the Columbia’s Canal Flats headwaters and up from the mouth of the river. We prayed for the river in 5 languages that day and the salmon dancers from the Okanagan Nation Alliance did their salmon dance.

NWNL Bill, would you read a favorite passage from one of your books?

BILL LAYMAN Yes, and since you talked about the Kettle Falls Ceremony of Tears, I’ll read about that from my book, Native River [p 158].

“Ceremony of Tears. On Sunday, June 13, 1941, Indian people from both sides of the border gathered at Hayes Island to honor and grieved –”

“– The falls soon would be inundated by Grand Coulee Dam. For three days, many spoke to the memory and meaning of the Falls. Among them were Chief Joseph Seymour of Kelley Hill, Sampoil leaders Jim James and John Frank, and Kalispell chiefs Pete Helakeetsa and Pete Joseph. They spoke of Kettle Falls as a place their people had known since time began — the vital center of a lifeway that had been thousands of years in the making.

Reflecting on the falls fifty years later, historian/archeologist David Chancellor wrote:

“Kettle Falls was the focal point of society and culture, the place of abundance, of great dances and marathon gambling games in which the wealth and commodities found their way into new channels. It was the largest cluster of villages for more than a hundred miles in every direction, the place to go to for variety, for news, for giving and receiving of gifts both promised and unexpected, the place to hope for a windfall, to discover the prospects for marriage, to look for a relative or friend long lost, or to consult and consort with powerful shamans.”

—From “People of the Falls (Kettle Falls Historical Center, 1986).

Multiple losses were felt that week. It was a particularly sad time for those who had been forced to move their homes from Grand Coulee Dam reservoir area. The people reflected and prayed –gone the salmon, gone the favorite places along the river where other fish might be caught, gone thousands of acres of bottomlands and access to root and berry grounds.

On July 5, 1941, Kettle Falls disappeared. It’s inspiring beauty — the foaming, surging, roaring, tumbling, mists, sprays, and shimmering rainbows in the sunlight – covered beneath the newly created reservoir.”

NWNL Thank you, Bill. That poignantly describes both the beauty and tragedy of 1941 – that first year after the Grand Coulee dam was built.

BILL LAYMAN Yes, in 1941 they closed the river. Several runs of salmon migration sequenced throughout the spring, summer and fall seasons, including a summer run of Chinook salmon and a fall run of sockeye salmon. The reservoir began being flooded in June and July 1941, so that’s when salmon could no longer swim upriver to spawn. Instead, the salmon came up to the dam. They kept hitting it again and again, because their migratory sense was so strong.

NWNL That is a poignant and tragic note on which to end our conversation; but thank you so much, Bill, for all you’ve recorded in books and exhibits – and for sharing your time and insights with No Water No Life.

BILL LAYMAN You are welcome.

Posted by NWNL on November 26, 2023.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.