The Raritan Riverkeeper

Raritan River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Raritan River Basin

Bill Schultz

Raritan Riverkeeper

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director and Photographer

Peter Berman

Video Producer

Julie Eckhert

Video Editor

A dedicated watershed steward, Bill Schultz truly loves the water and could be named the Raritan River’s “Wind in the Willows.” He is committed to communicating his passion for the wonders of the Raritan Bay with as many people as possible. He kindly invites all interested to enjoy and join him in investigating the wonders of the Raritan Bay from aboard his boat. His “co-hosts” can include whales and dolphins that swim around Sandy Hook from the Atlantic Ocean into the Raritan Bay!

RIVERKEEPER ISSUES & RESPONSIBILITIES

FISH ARE FREE – BUT CONTAMINATED

NON-POINT POLLUTION

SEDIMENT POLLUTION

AN UPSTREAM-DOWNSTREAM “WATERSHED CONCEPT”

RIVERKEEPER ISSUES & RESPONSIBILITIES

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

NWNL Hello Bill! Thank you for taking time out from this busy day of Rutgers University’s first Sustainable Raritan River Initiative meeting. This is a great gathering full of discussions between Raritan River stewards from the Upper North and South Branches of the Raritan, the Lower Raritan, all tributaries and the Raritan Bay – the latter being your bailiwick!

Let’s start this interview with your defining the job of a Riverkeeper.

BILL SCHULTZ Basically Riverkeepers act as a spokesperson for our water body. We’re water-focused sort of neighborhood watch. We speak for the fish and sue polluters.

NWNL That’s as basic as it gets! I like that.

BILL SCHULTZ One example of our focus is that we attend public meetings, to listen to and open discussions with developers who want to build, politicians who are worried about their tax bases and people who just want to use the river for recreational purposes or other purposes. I will be there to get up and talk for the river, for the birds, the fish, the animals and some cases for the people that use the river who aren’t necessarily represented.

NWNL From your experiences, what are the biggest problems affecting the river?

BILL SCHULTZ Probably the biggest problems affecting the Raritan are historic. Fortunately, we’ve cut down, limited, and in many cases eliminated ongoing pollution sites.

NWNL You don’t mean there currently are no more polluters on the river, do you?

BILL SCHULTZ No! There certainly are still polluters on our banks. But most of the issues that we deal with now are historic, including old industrial sites producing storm water running off across contaminated grounds and into the rivers. Bound Brook, South Bound Brook and Manville have an industry legacy where all sorts of things were dumped in the river, as if it was an industrial garbage can.

We also have dump sites that, although closed many years ago, don’t meet today’s standards. Today’s rainwater soaks through those dump sites and leaches out to the river. Polluted river sediment is a big remaining issue that we are facing.

NWNL What problems do you face due to polluted river sediment?

BILL SCHULTZ The Raritan’s riverbed is mostly shale below its North and South Branches and in the Edison-New Brunswick area. That rocky riverbed has a long history of industrial abuses.

In storm events, a basically rocky riverbed flushes its toxins further downriver to settle into riverbed sediments at the bottom of the river. Toxins have tumbled downriver for years, with many buried in sediment. Every time we dig into the sediments, we remove toxins that have been there for generations; or we re-suspend them in the water column so they are then flushed further downriver, contaminating a larger section of river.

NWNL Those who don’t pay attention to this river would be surprised to know that there are parts of the river where people are told “Don’t swim” and “Don’t do anything there.” How bad is the Raritan’s pollution?

BILL SCHULTZ How bad is it? Well, the state issues consumption advisories on many of the fish species here. I often think this is one of the worst times for the river, as far as the people are concerned. We went through a period where industries with liquid waste would just dump it in the river – because it’s the Raritan. People used to say, “Nobody’s going to eat the fish from there. Nobody would swim there. Just dump it there.”

Well, moving from those days, the Raritan is now making a recovery. Government agencies and regulators are looking at what’s going on. We’re all working towards “swimmable and fishable” waters, and we’re starting to see fish coming back. Anadromous fish are migrating and breeding in our river, as documented by several species. The fish are coming back. I hear people are catching striped bass – the highest I heard was 58 pounds in Highland Park – probably 10 miles from the Raritan Bay.

NWNL And are they safe to eat?

BILL SCHULTZ No, the state has consumption advisories on them.

NWNL How do those advisories work?

BILL SCHULTZ It depends on the species. Some suggest not eating more than 1 local fish meal per week. Some species should only be eaten only once per month. But that’s better than when we recommended only one meal per season!

JULIE ECKHERT What makes some fish more contaminated than others?

BILL SCHULTZ That’s determined by the contaminants that different fish pick up. Many of the migratory species just come upriver, breed and leave. They’re not too badly contaminated. With other species living in the river, contaminant levels depend on what they are feeding on! Many feed on worms that live in sediments with decades of industrial waste buried there. As the toxins move up the food chain contamination continues.

I think of this as one of the worst times for the river. But hopefully, it’ll only be several years from now that the fish will be safer to eat. If we keep addressing this issue the way we are now, there won’t be a problem. People will be able to go down to the water, throw a hook and line in the river, catch a fish, take it home and eat it without concern.

Years ago, there was no concern…, because nobody would fish. It wasn’t even a thought! Now, we’re in a “middle” period. The fish are here, they look beautiful, they’re a nice size; but are they safe to eat? That’s the question.

NWNL So today people are fishing, eating their catch and probably getting ill…?

BILL SCHULTZ We know people are fishing. We know people are eating those fish. I did a fish consumption survey for the state 2 years ago. I went around to different fishing places that I knew to interview fishermen. I asked, “What are you catching? What are you doing with your catch?” We found people – especially in the areas of Perth Amboy, New Brunswick and up on the Arthur Kill around the Carteret area – having to feed their families with fish they’d caught.

There is a homeless population that lives along the river in the New Brunswick area, fishing every day. They subsist on fish from the river. We could suggest they only eat one meal a month. But that would be the only meal each month that they would eat because they have no income. So, these are “subsistence fisherman.” We know they exist. What do we do with them?

NWNL It’s a terrible problem.

BILL SCHULTZ It shouldn’t be a problem, but at this point it is.

NWNL You’ve said there is minimal new pollution coming in from industry now.

BILL SCHULTZ Well, any industry sited on the river now must meet the current standards.

Compared to other states, the state is doing a somewhat decent job from that standpoint. Yet, ongoing pollution is still taking place at some sites. Fortunately, any new industry must meet current standards, and so there’s very little pollution coming off those sites.

NWNL What about non-point pollution, that which isn’t site-specific? Isn’t that a bigger issue?

BILL SCHULTZ Oh, have you opened the can of worms! Let’s start this discussion with what you consider a “non-source” issue.

NWNL Well, I understand non-point pollution to come from an undefined, perhaps wide-ranging source. Do you agree with that, or do you have anything to add?

BILL SCHULTZ Well, with that definition, you need to ask whether stormwater is a point- or a nonpoint source?

NWNL All right, let’s use another, perhaps simpler concept….

BILL SCHULTZ Let’s look at farmland situations. Most of the usable farmland is in the Raritan’s South Branch and North Branch watersheds. I haven’t seen and don’t know much about whether their runoff causing pollution problems for the river.

Regarding stormwater issues, I think that if you take stormwater off the street via a pipe that dumps it in my river, then that is a “point source” with standards you should have to meet. Not everybody agrees with me. Some regulators say that stormwater is rainwater; thus, it is a nonpoint source. That’s a handy excuse.

NWNL This is a complex issue; and it seems there are many ways we pollute the river.

BILL SCHULTZ This is absolutely a controversial issue. Earlier today, the Mayor of Edison mentioned people need to start cleaning up after their pets. We have to pick up after any dog that goes for a walk. So, what do dog-owners now do? Many pick the stuff up, put it in a plastic bag, and then throw it in the catch basin – not realizing that what goes in the catch basin will wind up in the river. Our catch basins are a direct source to the river!

NWNL Where should people put pet waste?

BILL SCHULTZ In a waste container or in the garbage. Just don’t put it where it will flow to the river. We’re working on state regulations that can help us by marking storm drains and catch basins. Many of our municipalities in this area – if not most – mark the storm drains that go directly to river. In some cases, they label what stream or river they drain into, helping people realize that everything that you throw into the gutter, even the oils that drip off the cars, goes into the river.

I’ve even seen impacts concerning pollutants from tire compounds. As we drive down the street, our tires wear out. Thus, we leave pieces of compounds in our tires along the roadways. They all flush down the gutter; into the catch basin; into a larger pipe – and eventually, in many cases, out to a waterway. Thus, both dumped tires and their compounds can pollute a stream or a river.

NWNL Thank you for highlighting that commonly unrecognized issue. Do you think people can be convinced to significantly change their lifestyles in order to have a clean river?

BILL SCHULTZ I wonder what you consider to be a “significant life style change.” We must start thinking about how to dispose of our waste and what new practices we adopt. But I don’t consider those to be a major lifestyle change. I think it’s being cognizant of what we’re doing and the consequences of our actions.

For instance, what happens when someone in a car tosses a cigarette butt out the window, rather than putting it in the ashtray? Where will do cigarette butts wind up? Where do they go? What animal will be impacted by the components of a cigarette? Will they ever completely dissolve?

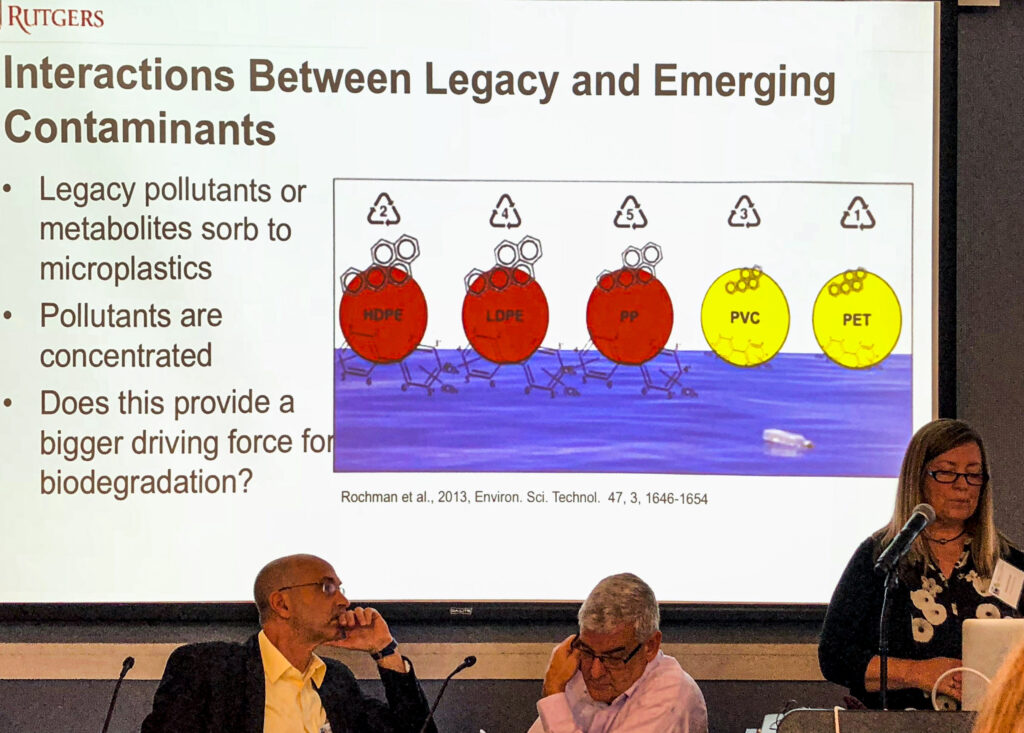

JULIE ECKHERT You talked about new pollutions having to meet new standards and criteria. But what can be done with the old pollution that’s sitting there? What can be done today about this “legacy pollution”? Are there solutions to addressing historic contaminants?

BILL SCHULTZ Quick answer? Yes, legacy pollutants can be removed. But we debate how and what can be done with it. It can be removed safely with technologies such as suction dredging. Rather than shoveling out toxic sediment, we can put a suction dredge down in the riverbed to remove the mud with toxins and pollutants. So, yes, they can be removed. But the question is, “Do we want to remove it and go through the expense of it?”

A big benefit of today’s conference is that people start to realize why we can’t just point the finger at a particular industry and say, “Go clean up your mess!” We must look at the nature of the river, characterize the whole river and examine its sediments – not just consider one particular project. For instance, one member of the audience said, “You should look at studies done for the New Brunswick Landing Project where they dredged a section of the river. ”Well, we didn’t necessarily agree with the way they studied it, in that they allowed blended sampling, i.e., blending several samples into a composite. But we know there are hot spots of toxins.

Any hydrologist looking at the river’s currents can say “Well, the river flows in a manner, so that certain toxins, depending on weight and how they’re dispersed, will collect in certain areas.” We can identify and study “hot spots;” but in so doing, we need to characterize their wider locations.

The problem we face is that everything is handled on a case-by-case basis. For instance, somebody will file a lawsuit against Company A. The first thing Company A says is, “Well, yes, we released this stuff – but so did this one and so did that one. I only contributed a small amount and so I’ll only do a small amount of work to help clean it up.” Where does that leave us? We must think about the river not just according to its pollution by one company.

We must start thinking of things regionally – what I consider the “Watershed Concept.” We’ve got to stop thinking, “Okay, here’s the Woodbridge border and here’s the Edison border. So, this is our problem, and that is their problem.” We must get away from that attitude.

We must start thinking, “We’re in the Raritan River Basin – all 1,100 square miles of it. That storm-drain, upriver in Clinton at the end of a cul-de-sac with little “Mac-mansions,” impacts fish swimming past Perth Amboy. We must start thinking that way, or else, we’ll just be beating our heads and putting band-aids on these problems – without addressing the overall problem.

NWNL Very good point.

JULIE ECKHERT Yes, we must follow the “Upstream-Downstream” issue NWNL highlights in all our watersheds. It is a great mission to help clean our rivers both upstream and downstream.

BILL SCHULTZ It really got to me one day as I launched off Route 31 in a kayak in one of the tiny little streams up there. We dragged our boats across rocks more than we paddled. Then, up in the northwest part of this state, we looked around – no train whistles, no highway sounds, nothing. Wow, just the birds. Or as one lady said, “Just the birds and the bees and wildlife – this is such a nice area.” It was hard to believe we were in the most densely populated part of the US.

Then we noticed houses under construction. And, son-of-a-gun, at the end of the cul-de-sac there was a storm drain, right above Spruce Run Reservoir. Wow, before any drop of water is harvested for human consumption from this waterway, we dump crap into it. We dump our road waste into the river before it even gets to the first point of consumption.

Someone once released a study saying that in the middle of the summer, if it’s a dry weather spell, more than 50% of our downstream water flow is sewage affluent. That is where something like 1.3 to 1.4 million people drink water from this river.

So, people, wake up! While kayaking upstream, I was so impressed with my river, saying, “Jeez, look at this – it’s so neat up here!” Then, all of a sudden, I spotted that damn storm drain. Oh, it’s frustrating.

NWNL Bill, I am sorry to end our chat on this note, but lunch break is ending and there’s obviously much more to discuss in the afternoon sessions of this conference. Thank you so much.

Posted by NWNL on December 26, 2023.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.