Cranbrook Stewardship

Columbia River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Columbia River Basin

Sharon Cross

Kootenay River Network, Montana

Laura Duncan

Kootenay River Network, British Columbia

Art Gruenig

Rocky Mountain Naturalists

Jim Clarricoates

Columbia River Intertribal Fisheries Commission

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director & Photographer

Robin MacEwan

NWNL Advisor

Fritha Pengelly

NWNL Videographer

Kootenai River Network

Impacts of Growing Populations

Bottled Water

Painted Turtle Conservation

Ktunaxa View of Columbia Fisheries

Restoration of Joseph Creek

Educational Opportunities

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.

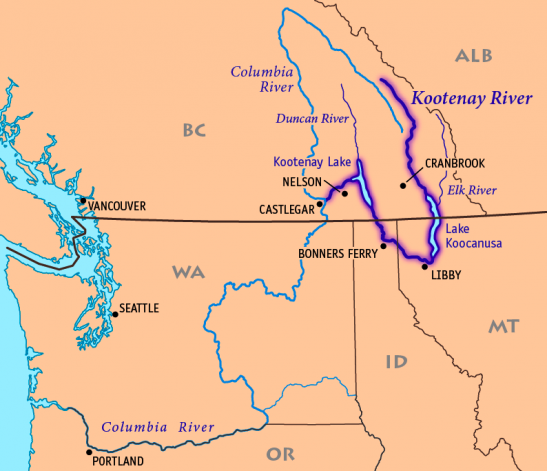

Hydrologic Note: Joseph Creek in Cranbrook, British Columbia is a tributary of the Kootenay River (spelled “Kootenai” in the U.S.), one of the uppermost major tributaries of the Columbia River. The Kootenay runs for 781 kilometers (485 mi) through southeastern British Columbia, Canada, and northern Montana and Idaho in the US. The Kootenay begins in the Canadian Rockies; flows south through British Columbia’s East Kootenay region into northwestern Montana and the northernmost Idaho Panhandle; and returns north into Canada in the West Kootenay region. It reaches confluence with the Columbia River in Castlegar, British Columbia.

For Further Information: Interviewee Sharon Cross recommends following Maude Barlow, National Chairperson of the Council of Canadian and author of many books, including Blue Gold, Blue Covenant and Blue Future. The Council is a government watchdog organization and umbrella group for those working on health and water issues.

NWNL Introductory Field Notes: Kootenai River Network’s science-based mission is to promote water conservation awareness and involve stakeholders in restoring the water quality of British Columbia’s Kootenay River Basin and Montana and Idaho’s Kootenai River Basin. Working toward creative, across-the-border solutions to water degradation, KRN hires scientists, technicians, and botanists to recommend actions and support grassroots ”citizen scientists.” KRN’s science-based stream curriculum for elementary students includes, a table model of the river that travels in a trailer from school to school to demonstrate how streams work. When NWNL arrived in Cranbrook for this interview, KRN had just completed a $93,000 restoration of Joseph Creek.

NWNL Thank you all for joining us as we begin our first NWNL expedition. We will be documenting the Columbia River Basin from its Canadian Rockies source to its terminus into the Pacific Ocean at Astoria. We will be following the main stem but also tributaries such as the Kootenay River in BC, which is named the Kootenai River when it dips down into Montana and Idaho. Sharon, can you begin by describing the mission and methodology of the Kootenay River Network?

SHARON CROSS Kootenai River Network [hereafter, KRN] is an education outreach and restoration organization, more than a political organization. We can’t lobby or verbally support any particular candidate; however we can provide information. It’s a fine line. Some groups in the forefront pushing for changes are more advocacy-based than KRN. I guess you could call us soft-edged. We hope our educational outreach will build a groundswell of support amongst the community.

When we talk to the city about actions such as putting in water meters, they say: “Listen, we first need to know that the community is going to accept that and that there won’t be a huge backlash.” So our group needs to get the community to buy into these ideas so the politicians know that they won’t get killed for doing what they know they should. That’s our roundabout route of not being political.

KRN is based on science. We collect the data; we do the research; and we do the in-stream science. From that, we have facts to present to the community that create the foundation for education and the conservation.

NWNL Do scientists do that, or citizen scientists or a combination of both?

SHARON CROSS We have quite an expert and multi-talented board. Jim Clarricoates of the Canadian Columbia River Intertribal Fisheries Commission is on our board. He is a fisheries technician and member of the Ktunaxa Nation.

JIM CLARRICOATES In my work with the Canadian Columbia River Intertribal Fisheries Commission we help create Indian stewardship boards, identify stakeholders and private landowners, and organize them so that they can represent their interests and take an ecological role. Our technicians support and advise them in collecting data.

SHARON CROSS KRN uses science through using organizations like Jim’s. But when it comes down to doing larger projects, we hire contractors and scientists at many levels. We hired botanists and fisheries biologists to give us the science on Joseph Creek. Their fisheries, water quality and water quantity information motivated us to protect this creek. Thus, we bring science to the citizen scientists.

We started a Creek Science Program that goes into schools and through a public leisure and recreation program for the general population. Although there weren’t enough people to make it go this year, the intent was to have Cranbrook citizens monitor the stream on an ongoing basis. Using citizens on work parties gives them background and knowledge in stream monitoring.

NWNL Laura, if Sharon supports this group’s vision because the treaty was originally a political one, why did you get involved?

LAURA DUNCAN Water is pretty clearly going to be of the top issues — if not the number one — in the coming century due to changes in climate and weather. We are going to have less water and need to be a lot more careful with it. We are going to lose huge amounts of habitat when we have less water. There are growing demands from growth of population, development, and industry. There’s growth everywhere you go. This area is exploding.

Invermere is facing phenomenal growth and already is in dire straits for water. Their lake is in extremely bad shape. Yet the community continues to grow while the supply of water continues to diminish. I’m interested in getting a handle on this. How do we cope with the competing demands of diminishing resources and simultaneous increasing demands on them? We are not very smart about it.

Getting awareness out to the public and the politicians is pretty darned important. Scientists have known this for a long time. So a huge part of our role is to get information from scientists we hire to this area’s general population and politicians. We’ve concentrated on Cranbrook to date; but we’re expanding — both with our sister organization across the border and within the Columbia Basin on the Canadian side. We need to work the other side of the border on similar issues to address the lack of understanding. The general population across the border seems to be less aware of coming effects from climate change. I think there is a bigger job to be done just south of the border.

NWNL Are you talking about a national United States’ attitude or specifically your U.S. counterparts within the Kootenai watershed?

LAURA DUNCAN It seems that our American counterparts just across the border in Montana have much less public perception of climate change impacts that are coming and the science behind the newest predictions. At this point I don’t really care whether climate change is human induced or not. It is coming, so we really need to learn how to adapt to it for whatever reason.

NWNL Is Invermere‘s exploding population a local population growth or a new work force? Is it from the United States or Canada?

Development in Invermere around Lake Windemere

LAURA DUNCAN It’s recreational. Alberta has an exploding petroleum industry, lots of money and people wanting a lovely playground. Those forces are dragging up prices. In Invermere, there are two new golf courses going in. Beyond Invermere, there are about several thousand new people in the north area of our town. The whole trench is feeling pressure because of Alberta.

Invermere got it first because it’s at the end of the highway coming through the National Parks. So they have taken the brunt. Kimberly is now going crazy. Housing prices have gone nuts. In one period last year the house prices went up 30% in two months. Cranbrook and Fernie are also starting to feel it. The whole basin is facing tremendous growth.

People buying recreational pieces of property are not only driving up the prices, but they are not residents. They are there for holidays, weekends, skiing vacations or whatever. Many of them really care deeply for the land, but aren’t living there. They’re not available to be volunteers that make things work. They don’t vote for building a better life or better resources for the seniors because they are not there. They don’t need those civic resources, so why would they vote to raise their taxes for a better library for school kids? In general, already 30% of homeowners are nonresidents.

NWNL Are there any models that deal positively with this growth? What’s needed to do that effectively?

LAURA DUNCAN There is an organization on the coast of Vancouver called Smart Girls of B.C. They have good ideas about development. Communities here are beginning to think in a way that most of our politicians haven’t yet. What we are working on is to build acceptance of the facts before we are at the crunch and it’s absolutely a disaster. Let’s do something while we still have flexibility in our responses, instead of just “Oh, my God.”

[Sharon Cross discussed British Columbia’s Water Protection Act and her letter opposing applications from water-bottling facilities. The BC Water Minister had told her 2 weeks earlier they were working on addressing loopholes and other problems with their Water Action Act. See the current Water Protection Act online.]

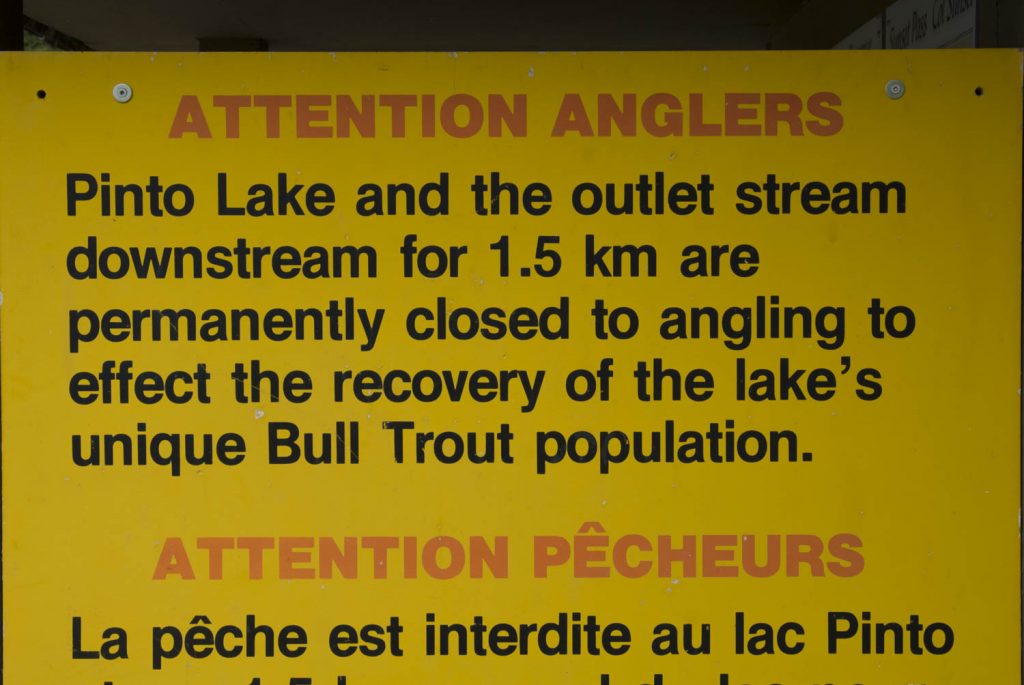

Signs seen throughout the Kootenays

NWNL Why are you opposed to water-bottling facilities in your region; and how will British Columbia’s proposed “Water Action Plan” address loopholes and problems with the Water Protection Act of British Columbia?

SHARON CROSS The Kootenay Region is called the “Serengeti of the North.” Yet we have problems. Legislation needs to be tightened up to prevent huge water extractions. The water from our taps is very drinkable. Plastic bottles often don’t make it to the landfill site to get recycled. So, what we are doing with bottled water?

Large water-bottling corporations come in, make deals with municipalities and promises. They extract water for something like a millionth of a cent; bottle it; and sell it for more than we pay for gas. Go figure! The profits are huge — but at what cost? We need to catch up with what’s happening globally and address these kinds of issues in terms of our legislation.

NWNL Art, how did you get involved in conservation?

ART GRUENIG I retired 17 years ago when I was sixty and came here to get my life established. I take an interest in what’s going on. I read a lot. I understand the sentiments. I manage a 45-unit complex and do little things like getting people to recycle. Instead of two truckloads of garbage a week, it’s every two weeks now and the rest is recycled. I recycle bottles, pop cans and stuff. I use wood for building birdhouses and stuff like that. It’s awfully small compared to what others do. But, I participate in ordinary conversations with the older people who are my age. I tell them, “Hey, things can be done and done well, one little deal at a time.”

When the center was going to build a road through the park, people around that I’d gotten to know asked if I would do anything. Nobody else stepped forward, so I did a bit of advertising the paper and we raised a little bit of hell. I’d stand on the trails so people would come to see what we were doing; and I’d say, “Go down to City Hall, email them, fax them.” My God, that’s what they did. They tied up the lines so bad that City Hall was shut down for a week. We had no business for a week. City Hall folks kept phoning me and they were mad. They said to call off our hounds. And I said, “No.” After a third meeting on “No Road Through the Park,” I told them to quit. And there was no road. It’s out of the 20-year plan. That’s what I mean that one person can make a difference. It’s just little individual things that we can do — even if I feel awful small when at least thirty people talking.

NWNL Art, it seems you started a significant movement.

ART GRUENIG Oh yeah. Even though I feel that I’m not doing anything, when I hear other people saying they can’t do anything, I have to say, “But I just do one job, one little thing, at a time.”

NWNL Art, tell us about your conservation efforts to protect Painted Turtles (Chrysemys picta).

ART GRUENIG Well, they were crossing the highway in big numbers to nest in the rocks and sand up in the hills across the road. Every morning I’d see maybe 5, 6 or 7 dead on the road. Columbia Basin Fish and Wildlife came and then called a meeting. Clubs like ours, the Rocky Mountain Naturalists and a few other people became concerned. I felt out of place because I only had a little piece of paper that said it could be stopped for about $5,200. But these other people were talking about creating a cement box down on the road and digging tunnels underneath the road. Their project was running into $200,000–$300,000.

There was no way my project was going to fly. So I got up to leave. When asked why, I said, “Well I don’t have much to say.” They asked, “What’s that paper in your pocket?” I reluctantly took it out and said, “We need a two-foot fence down the side of the road, made from posts that I was talking to the realtor about. The railroad was pulling cement or steel posts that I figured we could cut in half and pound 2 feet into the ground, leaving two feet above the ground. We’d run wire along. We did that. That was seven years ago.

We’ve had only three turtles killed since. The fence was run over the other day. Seven of them got out. I saved six. Twenty-six nested this year, rather than what used to be maybe five or six. They know they are not going to get through the fence, so they just come up and dig their nests, lay their eggs and they are gone. So the solution was quite simple: $5,200.

Next came the skunks and the badgers. Skunks dig up the eggs and kill the young ones. I lived an hour south of here in Preston where the painted turtles nest. It’s two degrees warmer down there and so the hatchlings get out in the fall, leave the nest and run to the water. But in Cranbrook they stay in over for the winter and go to the water late April or early May. The mortality rate in Cranbrook is a lot higher here because skunks smell the eggs, dig them up and eat them — both as soon as they are laid and in the spring.

Once a badger took over in the park for two years. It takes a lot of food to feed a badger and its young ones. They do a real quick job going into the turtle nests. I cut mesh into 18” squares and put it over top of the nests. I raked the sand every day until the turtles came up with their bellies full of eggs. They move just like a stone boat on the sand! You can follow them to see where they nest. Over top of them I put the cage that badgers can’t dig under to get them. The badgers left and we haven’t lost any turtles now for about a year.

I go to see them every day. There was a guy that used to walk on the turtle nests every day with his friends. They walked right over them, packing the sand down, making it harder to get the young ones out. The morning before last, I got up at 5:00 am and caught them. There’s been no traffic since down there.

NWNL Are painted turtles endangered, or under threat here?

ART GRUENIG They are not endangered, but this is close to the northern part of their range. So they are not as plentiful here and they don’t reproduce as well. Thus we can’t have six or eight being killed in a day, otherwise they’ll be an endangered species. But by doing the fence and putting articles in the paper, people are learning about them and starting to treat them a little differently.

NWNL Jim Clarricoates, you are a member of the Ktunaxa Nation and with the Canadian Columbia River Intertribal Fisheries Commission. How did you become interested in becoming a fisheries technician?

JIM CLARRICOATES I got into fisheries natural resources when I was 17. Because I had a good back and strong arms, I began working in forestry, often in terrible weather. That wasn’t for me, so I went to the creeks. Fish have been important to First Nation people from time immemorial, so the mandate for the Columbia Kootenay Fisheries Renewal Partnership is to promote stewardship of the resource. The Ktunaxa are actively involved in trying to restore salmon to the Upper Columbia. There is even a spawning bed up in Columbia Lake that they used to reach. Restored access to that spawning area is one of the main goals for the Canadian Columbia River Intertribal Fisheries Commission. We also want to ensure that our native fish have their home range despite the introduction of exotic species and hybridizing of trout species.

Without The Columbia Basin Trust, a lot of this work wouldn’t be done. They are actively updating their programs of funding landowners as well as industry stewardship. We try to help them as much as possible with private landowners interested in resources. We pretty much bend over backwards to get programs running. We set up monitoring programs so streams have enough riparian species and large woody debris and so that they can maintain proper temperatures.

NWNL You also work with a lot of small NGO’s don’t you?

JIM CLARRICOATES Yes, we work with non-governmental organizations, including Wildsight, Slocan Stream Keepers and Salmo Watershed Stream Keepers. They do amazing work in their respective watersheds. We like to help them pop up onto the radar so the community knows where to bring up issues if they see something going wrong.

Salmo Stream Keepers

I also sit on the East Kootenay Integrated Lakes Management Partnership. This is a partnership of a few NGO’s, but mainly governmental agencies working throughout the Kootenays to establish baseline information on the lakes. We make recommendations for maintaining those lake ecosystems.

NWNL What has to happen to bring the salmon back here to spawn? What is the likelihood that could happen and what would be the timeline?

JIM CLARRICOATES The main push was begun in the mid-seventies by Chief Paul Sam from the Shuswap Band near Columbia Lake and Wilford Jacobs from the Lower Kootenay Band. They were the biggest advocates for the restoration of salmon. Paul Sam is still out there giving us crap because the fish aren’t here yet. Unfortunately, we lost Wilford Jacobs a few years ago, but I keep on working in his memory.

We just did a Feasibility, Impacts and Benefits Assessment for the restoration of natural salmon with agencies from both the United States and Canada. The Bureau of Reclamation and Army Corp of Engineers were there and there was a positive attitude about doing feasibility studies. In three years they’ll bring some tagged salmon into Lake Roosevelt above the Grand Coulee Dam to track. One worry if the salmon could get above the dam is that they wouldn’t know where to go, or they would just turn around and head back downstream. That is a project that we are going to be working on.

[For update, see Oct 2014 Report by Columbia Basin Tribes and First Nations: “Fish Passage and Reintroduction into the U.S. & Canadian Upper Columbia Basin” on the continued efforts and feasibility of reintroducing salmon above central Washington’s Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph dams, significantly improved due to fish passage technologies and research tools.]

Grand Coulee Dam

NWNL What effect do the smelting mines and pollution between Lake Roosevelt and here have on fish?

JIM CLARRICOATES Actually, I’m really impressed with the Tech Cominco smelter [in Trail, B.C.] because they have really cleaned up quite a bit. Their technology has increased and they have cleaned up their effluence, as has the Celgar Pulp Mill [in Castlegard, B.C.]. It’s a slow process, but the science is getting better; and like the White Sturgeon Recovery Initiative, industries are helping to pay for the studies and coming up with ideas. Juvenile sturgeon releases have been an interim measure until we can find out why white sturgeon aren’t reproducing. There are spawning events, but it seems like the juveniles are not surviving. So we have a large population of adults and no juveniles. With Freshwater Fish Society we have been transplanting fish along the Columbia. This year they began an annual transplant at Revelstoke above the Arrow Lake generating station. There are a few problems with fluctuating reservoir levels, but I think the logistics will work themselves out by next year.

NWNL That’s all good news.

JIM CLARRICOATES I try to keep that positive attitude so that everybody can see that this is a good thing. This is something to be excited about.

SHARON CROSS The regulation of the dams pose many problems because of competing interests regarding water releases. Doing what the salmon and sturgeon need might not be what the recreationists with houseboats and businesses on the reservoirs want — so this creates conflicting interests competing for that water.

NWNL Where do your salmon stocks come from, perhaps the hatchery here?

LAURA DUNCAN We are investigating some stocks that we can use. That’s why it’s going to be a three-year time period. It’s most likely going to be a Columbia River stock.

NWNL What are the invasive species issues in the Columbia River?

LAURA DUNCAN Walleye are voracious predators introduced into the Columbia. The Ministry of the Environment is trying to eradicate Northern Pike with gill netting and other techniques because they too are predators that follow salmon and other native species to their spawning sites to gobble up all the eggs or catch them when they are emerging. Brook trout are also being introduced broadly. There are some in this creek.

NWNL Could you talk about the importance of Joseph Creek to fisheries?

LAURA DUNCAN Oh, Joseph Creek was huge for bull trout fisheries. In the lower section there is an historic wetland area for Joseph Creek, mainly down by the malls there. It was very diverse for wildlife, waterfowl, and fisheries. I can only imagine how beautiful it would be. Along the lower section folks used to place fish traps because it is a pinch point. This is one of the central areas for the Ktunaxa peoples — here and in the Tobacco Plains area. I figure this would have been mostly a hunting area, but the bull trout fisheries in the lower end were very significant as well.

Left: Cranbrook’s Joseph Creek. Right: Invermere boardwalk sign.

NWNL Is there support and involvement from your people and involvement, or resentment and disinterest?

JIM CLARRICOATES There is a lot of support, but our capacity is low because we are a small tribe — one of the smallest tribes in North America. It’s hard to gain the interest of the younger generation. Fifteen years ago, people probably would never have thought that I would work in fisheries because of my rowdiness. But after a while youth settle down and take interest, often pouring their heart into something. For me, that’s what the creeks brought. One night I was in Yahk [Yahk Provincial Park in B.C., 70 km south of Cranbrook] just enjoying the evening. Then I swear I could hear a powwow coming from the waves [of the Moyie River]. I could hear the songs; and that let me know that I was doing the right thing.

NWNL What was the problem you were facing with Joseph Creek?

SHARON CROSS The city rated this park as a walking place, a soccer field, a nice green space within town, but what they did was clear out all the riparian vegetation. They used to actually “weed eat” the grass right over the edge of the banks of the water, and people loved it. There were great intentions for the enjoyment of the citizens of the city. But they weren’t good for the fish.

NWNL What stimulated restoration of Joseph Creek?

LAURA DUNCAN As Jim was saying, this creek was a very important fishery, probably the best juvenile recruitment of a fishery on the St. Mary system. The St. Mary is one of the major tributaries of the Kootenay, which is one of the major tributaries of the Columbia and a very, very important fishery because of lots of spawning in areas. Yet this creek has gotten the typical run of urban impact. It’s been subject to channelization and culverts that are fish barriers; city run-off and sediment running into the creek and smothering spawning channels; 90-degree turns; and loss of riparian vegetation. The creek also has a lot of demands placed on it by the city in particular and by a number of other people with water licenses on it. Three or four years ago, in the summer, it actually ran dry at the city. At that point a number of groups formed an umbrella organization called the Joseph Creek Community Action Team. Jim’s organization is part of this team and another handful of other groups. KRN decided that we couldn’t put off working on this creek anymore, so we kind of coordinate the groups.

When one of your major fisheries runs dry, it’s not a good thing. We decided a restoration project would be one of the best ways of bringing some attention to the creek. This park is owned by the city so we’ve worked with the city to raise their awareness and to use a small restoration project as an educational tool. We don’t pretend that this going to fix the river. Our intent is to build support in the community.

NWNL How did you work through the design process and who was involved?

LAURA DUNCAN The original project we designed called for 32 in-stream structures, but due to a number of flooding concerns and lack of funds it was cut back to 10 in-stream structures, in association with that of riparian planting program. Getting permission within city limits is quite convoluted and pretty difficult. Engineers must sign off on everything and you have to have your ducks in a row. But the process of going through city council also gave us an opportunity to educate them. Just having a proposal brought forth raised many questions and a lot more awareness on the part of the council and the community itself. We are pretty pleased at actually getting permission to do this at all.

Now this project is a process of monitoring and seeing whether the structures that we put in place actually do what they are intended to do. Each spring we do a bird survey with Art’s group, the Rocky Mountain Naturalists, to see if increased riparian vegetation will have an effect on the bird life. But our riparian plantings are only a year and a half old, so we are not seeing any changes as of yet.

Birds of British Columbia

NWNL What have been the benefits to the community of this restoration project?

LAURA DUNCAN We use this project pretty extensively as an educational tool. We bring school classes and college classes here. We have events open to the public. We hold activities on the stream where kids get into the water and do some monitoring activities. We hold work parties where people get a bit of information thrown their way. We have produced pamphlets, articles in the paper, and things like that. So this is a tremendous educational tool for us.

At the same time hopefully we’re having a bit of a positive impact on the creek before it has a huge impact on the fisheries population. I know there are a lot of problems downstream that have to be dealt with in terms of fish, but we are creating some better habitat if the fish could get here. In the meantime we hope that we can, at some point, expand this footprint. Public awareness is a huge part of why we do this. Thus, we are building a water conservation program; we’re having little contests; and we are about to start working with developers of all sorts within the community — whether residential or commercial or industrial. We want to convince them that it is in their best interest to do their developments in a way that is friendlier to the water resources in the area. So that’s where we are going to put a lot more time.

NWNL You mentioned creating 10 in-stream structures. What are they?

LAURA DUNCAN They are logs with the root wads attached and combined with big boulders. Basically we peeled away the earth and placed 20 or 30 foot logs with their root wads in the water and buried the stem of the tree under earth. They are different shapes and combinations fulfilling different functions. On each side of those logs are large boulders, cabled together with logs and into the next boulder. They all become one unit and then they are buried. The intent is they won’t move in a one-in-200-year flood. They are designed to protect stream banks while the vegetation grows back; to divert the stream so it will scour out and develop pools; to provide shelter for fish; and to create shade to keep the water temperature cooler.

This stream, as Jim mentioned, was a very important bull trout stream. Well, today bull trout can’t survive within the city of Cranbrook because it gets too hot since there is just not enough shade. So bull trout are only able to survive in the upper watershed now. That is why we are shading the stream through these root wads. But over time the vegetation that will grow up here will be extremely important. Some of these structures lean more towards erosion control, some more towards creating pools, and all of them provide some shade and shelter.

Restoration of Joseph Creek banks with root wads

Part of our riparian planting involves 4,500 plants, most of which are so small that right now they can’t be seen in the grass. A huge part of this riparian plan was convincing the city to allow this area right next to the stream to not be mowed. So now we have all these lovely dandelions, which can be hard for some people to take if they like the very clean manicured look. Bringing that acceptance to the general population is an interesting part of the whole process.

NWNL In the states, when we install a stream restoration, we have to work with the local, state, and federal level. What is involved in Canada?

LAURA DUNCAN The same. The local and state province, i.e., the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, have their say; the local B.C. Ministry of Environment has to approve it; and in the end the city has to also say yes.

NWNL What about First Nations?

SHARON CROSS No, not in this particular case. On some land though I’m sure you have that.

JIM CLARRICOATES No, not really. Most likely any such First Nation involvement would occur in Crown Lands, but we’re not involved in that part of the government process. And we also have to apply for permits when we do our work. We are not part of the approval system. It’s a little different type of government.

NWNL Are there other similar restoration projects?

LAURA DUNCAN The City of Kimberly has a small restoration project developed by Wildsight that is quite different. It began in 1995 with a community workshop to find out what the creek used to be like, how it used to be used, how it is used now, what it’s like now, and what they want in the future.

Also, below Kimberly there is also an Eco-Park being developed on Mark Creek where Sullivan Mountain’s 100-year-old lead and zinc mine has created decades of high acidity in the water. In 1991 Mark Creek was tested at a pH of 3.1 when the spring freshet washed mining waste into the creek. Of course, there wasn’t a lot living in that Creek. It’s never going to be a pristine creek; but there are fish in Mark Creek now. There are more changes needed, but this was a huge, huge step.

NWNL What motivates these restoration projects in general?

LAURA DUNCAN A general consciousness is growing that we can’t go on doing this kind of thing. Wildsight evolved from a local environmental society. Legislation about mine closure and reclamation mandated a certain type of cleanup. The mine closed in 2001, although it will be presence there forever because of its acid-generating nature. Change has been due to legislation in a large part, as well as the public’s consciousness.

NWNL Was the public involved in the initial or consensual design process for this project on Joseph Creek?

SHARON CROSS No. Not in the design. We talked informally to people; the public had a chance to speak to the city about what they saw; and we had some outreach activities to present our ideas. But there was no formal process of feedback and consultations.

Other public inclusions involved putting leaflets in their mailboxes, getting information into the general population and that sort of thing. We didn’t go knocking door to door. There are certainly some people that are not happy, but it’s amazing how many people come by and say, “Wow, this is so neat. I remember that I was a kid, I would come here and catch a fish like this.” Or, “You know, we’d sneak through the bush to get to the creek and it is just so neat to see stuff come back.”

We did work with The Land Conservancy, a big community action team. When we started this process, they had what they called a Land Owner Contact Program that we sent to residents adjacent to the project, saying we’d like to come and talk about living on a stream with a healthy riparian corridor. It offered our services or input. Some people responded, asking The Land Conservancy to assess their property and give them ideas on how things could be different. We had vegetation available for them to use. When we did planting along here with professional tree planters, our planters would actually to plant trees on the properties of landowners who’d contacted us. Since then, many have come to us with comments, such as, “You know, I noticed over there….” Or, “I wonder if we could get some of those things?” Or, “What would you suggest here?” Many properties along here are getting undercut, especially those with grass right down to the banks. Those landowners are gradually losing some of their property.

NWNL Where did you get the model for this design?

LAURA DUNCAN A restoration biologist did the design and the work. This particular design is primarily for stream bank erosion. The water comes in at a curve where the city would line up big chunks of old sidewalks to protect the stream bank. That protected the stream bank, but offered nothing else to the stream. So our new root-wad structures replace those sidewalk concrete blocks. While they hold the banks in place, we’ll refill the void with shrubs and conifers so that their roots will hold the banks in place. These root blocks also provide some shade and some slow places that provide shelter from predators and places to rest. So our changes are multi-functional. But to someone who is used to seeing a nicely manicured little stream here this is a bit of a shock to the eyes.

Non-native willows, planted further down the stream, are really encroaching on the river. So we have spent quite a bit of time taking them out. We did a series of stream profiles last year after one spring freshet as comparison to stream profiles done before our work. There wasn’t as big a difference after one year as we had hoped, but we’re hoping for that this year since we had high water causing a lot of scouring and creating more diversity in the channel.

NWNL Your monitoring includes vegetation plots, photo points, and stream profiles. Anything else?

LAURA DUNCAN We hope to get fisheries surveys done. The St. Mary’s Band put in a proposal to do a fisheries survey this year. So that would be another aspect.

NWNL What challenges have you faced?

LAURA DUNCAN Trees planted by school children had to be replanted since there wasn’t enough supervision. There are also people who unofficially take water out of the creek, which depletes its supply. Our initial studies identified that as our number one problem. There’s not enough water when it’s hot. So we put a lot of attention on quantity of water. That fits in with our whole conservation ethic and our attention to local development. Meanwhile, kids come along and jump into this little spot. We have some great pictures of kids having a ball.

NWNL So you are providing recreation as well as restoration?

LAURA DUNCAN Yes, at no extra cost.

NWNL Were there any side benefits of this restoration project on Joseph Creek?

LAURA DUNCAN Yes! As we worked here during the restoration, people would lasso us to ask, ‘What the heck are you doing?’ And we would go through reasons and rationales. It was a much more useful way of sharing information than public meetings. A Rocky Mountain Naturalist came here and picked up dog poop, which resulted in huge publicity and kudos. For weeks after an article appeared in the paper, folks would go up to our work crew to ask, “Are you the guy? Thank you so much.” And so we got the opportunity to talk about other issues. Publicity and awareness comes in most unforeseen places.

NWNL What other methods of water conservation education have you experienced that are effective?

SHARON CROSS My husband is doing artwork for The Thompson Project, recreating early exploration in the Columbia River Basin. Thus we were invited to Bonners Ferry for a reenactment and canoe trip on the Kootenai River last May, organized by The Nature Conservancy of Idaho. The first night, author / historian Jack Nisbet talked about David Thompson exploring the Kootenai River. Biologists talked about the state of the river, its fisheries and sturgeon restoration. With that background, folks in 30 canoes and kayaks paddled the river on the same day that David Thompson did 198 years ago. We rafted up along the river so biologists could talk about their sturgeon traps, erosion and former wetlands. Jack Nisbet told stories about David Thompson and the river. We ended at David Thompson’s campsite where mountain men in period costume greeted us with black powder fired from their rifles. It was a fun way for people to learn about the river, its historical significance and the biology.

Storytellers from Kinbasket Lake, Okanagan Valley and Salmo River Basin

Similar events are happening on the Columbia River as well. Kindy Gosal, his Columbia Basin Trust crew, and glaciologist Bob Sanford (former Chair, United Nations Water for Life Decade) are often involved in bringing people to the river and educating our river basin residents. It’s important to hear the old stories. We’ll soon have a symposium in Montana with U.S. and Canadian representatives attending. Watershed education is in the air. It’s happening and transboundary cooperation and collaboration is stirring. The water is stirring.

NWNL Is transboundary participation of both U.S. and Canadian residents of the Columbia River Basin residents usual?

SHARON CROSS One of the most hopeful things going on right now is that small groups in this area and across the border are coming together. This Joseph Creek Project, for instance, has the Canadian and Columbia Tribal Fisheries Commission involved in partnership with our land conservancies. Local teachers are working with Wildsight. Organizations are coming together with Rocky Mountain Naturalists who are not on our team, but played a really big role in what we’ve done. So it goes. These broad coalitions are getting things done.

The water is drawing us together.

ART GRUENIG The Rocky Mountain Naturalists started out as a social club. Yet, while having fun, they are out there raising awareness of the river. Fun is important because it gets so much buy-in. People rarely say “Yeah, let’s do it because it is a good thing for us.” Instead, events with high social aspects snowball when matched to folks’ energies. It’s like working with family.

Posted by NWNL on Feb. 3, 2015.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones, NWNL Director.

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.