Saving New Orleans

Mississippi River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Mississippi River Basin

Paul Kemp

Geologist, Coastal Oceanographer & Commissioner of Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority East

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director & Photographer

New Orleans Levees

The Levee Authority & The USACE

Levees Outside New Orleans

Geological Processes

West Bay Diversion

Deltas Need Upstream Sediment

Bonnet Carré & Segmentation

Simplicity Begets Reliability

Connecting People, Floodplains & Rivers

Promoting Sustainability

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.

After Hurricane Katrina (2005), new infrastructure has protected New Orleans. Hours before Hurricane Ida (2021) hit Louisiana, Retired Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré, overseer of New Orleans’ Katrina recovery, endorsed that new $15 billion storm-protection infrastructure – and yet warned Louisianans: “Anything built by man can be destroyed by Mother Nature.”

Fortunately, those levees withstood Ida, saving New Orleans. In this 2nd NWNL interview with Paul Kemp, he stresses that America’s cities and resources require both extensive infrastructure and preservation of rivers, plains and wetlands.

“The whole universe depends on everything fitting together just right. ”

–Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012 film)

NWNL Hello Paul. It’s good to meet again in this cypress-tupelo swamp to catch up on your thoughts and local developments since our 2011 interview when you were with Audubon.

PAUL KEMP Yes, I left Audubon last year as CEO, after setting up that office and securing funding. For the past 18 months, I’ve been a consultant for them, focusing on coastal science as it impacts the public interest. I’m also now a Commissioner on the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority East, which manages the levees around most of New Orleans.

To improve flood protection, our Levee Authority has sued 97 oil and gas companies that abandoned their canals and damaged the marshes outside of our levees. We want them to repair that damage, as part of Louisiana’s need to enhance its levees and flood-protection system.

NWNL Some with whom I’ve talked avoid the term “flood protection,” because it builds expectations that can’t be met.

PAUL KEMP That’s a charade. People here think of it as flood protection, even if some call it flood-risk. We provide protection or we don’t – or we provide it to some degree. I think more important is understanding the level of protection that we provide – which is by no means enough, even with the very expensive structures newly built around the city.

NWNL How will you accomplish that added protection?

PAUL KEMP Two ways. We want to slow surges and diminish waves by putting infrastructure outside the levee system reducing the pressure on it. And we want to segment the city’s “protected areas,” so a breach in one levee doesn’t flood the whole city.

NWNL What is your involvement with the Levee Board?

PAUL KEMP We manage several Levee Boards: St. Bernard Parish, Lake Borgne Basin (which faces storm, river and rain-induced floods) and Orleans Parish. Further west, we are responsible for the East Jefferson Levee Board.

NWNL How did this Levee Authority evolve?

PAUL KEMP It was formed after Katrina’s levee failures destroyed the city to find a more systematic and comprehensive approach to flood-risk management. The Board was needed for acceptance of federal dollars and was part of a reform movement in New Orleans after the storm. The US Army Corps of Engineers (hereafter, USACE) held responsibility for flood protection. There was a sense that since USACE was not overseen by local engineers or being challenged, many poor decisions had been made over time.

NWNL Is it right that 8 or 9 New Orleans Levee Boards were consolidated after Katrina?

PAUL KEMP Those Boards still exist, but under two regional authorities. Mine is east of the Mississippi River, facing Lake Pontchartrain and Lake Borgne. The other is west of the river.

NWNL How well do the Levee Authority and USACE work together, and who has responsibility for that surge barrier?

PAUL KEMP That surge barrier is in what we used to call the MRGO funnel. When I was at the LSU Hurricane Center, Dr. Van Heerden, my colleagues and I identified that funnel as a weak spot in the flood protection system. It proved to be so. In the forensics report Dr. Van Heerden led, we suggested a pile-supported structure on the west side of Lake Borgne.

Shortly after Katrina, the USACE was not amenable to that idea. But when they were sued by people in the city and its parishes due to the MRGO flooding the city, they came up with a plan that included that type of pile-supported structure. The new surge barrier is a great improvement over what was the Gulf of Mexico’s entrance to the city.

That entrance is now closed, but doing so cost $1 billion. And if MRGO hadn’t been built, we might have enough wetlands there to negate any need for such expensive structures. So, it’s a bittersweet victory.

NWNL Is MRGO now closed?

PAUL KEMP MRGO is now blocked by the surge barrier. Since they replaced that barrier, we’re seeing a great reduction in salinity in the wetlands around there and in Lake Pontchartrain. It’s had a big positive effect.

NWNL Have those along the “Hurricane Highway” learned these lessons?

PAUL KEMP Some lessons have been learned; but it’s not enough to be learned once. For instance, many people in New Orleans now are recent migrants who weren’t here when earlier hurricanes destroyed the city. So their understanding of hazards facing this city is limited. It’s hard to imagine you’re facing flood threats, even though you may know you’re below sea level. One job for our Flood Authority is to continually warn people about that consequential threat – and the other is continuing infrastructure work to be supported by taxes.

NWNL Which carries the greater priority?

PAUL KEMP The highest priority is to put suitable armoring materials on the levees, so waves and over-washing doesn’t destroy them. We can tolerate a certain amount of over-topping water; but that can erode and breach the levees, which we can’t survive that. Just one breach equals thousands of feet of over-topping. We can’t take a breaching situation. We can pump a vast amount of water out of the city, but not water that’s coming in through holes in the levees.

NWNL Is it the earthen levees that need more armor?

PAUL KEMP Yes, probably 80% of New Orleans’ flood protection infrastructure is earthen levees. We do have flood walls, but their over-topping problem is different. The Corps has just handed us supervision of most of the levees along almost 300 miles. We’re now calculating these reaches and highest risks to target which need additional armor first and where to mound those levees to break waves.

NWNL Are there levees around industrial complexes south of New Orleans in the Mississippi River Delta? I saw Kinder Morgan’s huge piles of coal there and know there are proposals for more export sites. Jonathan Henderson from Gulf Restoration Network said the levees there are in terrible condition; have been breached before; and will breach again. Is your Levee Board responsible for them?

PAUL KEMP No. Those terminal facilities are just flat patches of ground next to the river. Some have levees in front of these facilities. In cases farther down the river on the east side (where there are no flood-control levees), coal arrives by barge or rail and is piled for transfer to ocean-going vessels.

One consequence of reduced US coal use is that there is now much more coal available to send to other parts of the world. So, we see a burgeoning of coal depots. What leaches out of piles like that?

NWNL Louisiana doesn’t require covers for coal, whether it’s on conveyer belts, trains or mounds. So, what are the consequences when a powerful storm comes through?

PAUL KEMP I’m sure those levees can’t keep storm surges out of the coal. It will spread around, as it has, really, for centuries. There is a long history of coal dropped along the way. The engineer, who designed jetties at the river’s mouth, had to collect spilled coal off the bottom of the river, so he invented a diving suit to do that.

NWNL If those levees are not under your purview, does anyone have responsibility for monitoring their height or strength?

PAUL KEMP Our tradition is to wait for things to break – usually in a disaster. So we rarely come up with a fix. We’ve been reactive, and are now trying to be proactive. But that very much goes against the grain in coastal Louisiana.

NWNL “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

PAUL KEMP Yes. There are so many problems that “potential” problems usually don’t get much attention, particularly if they involve an industry.

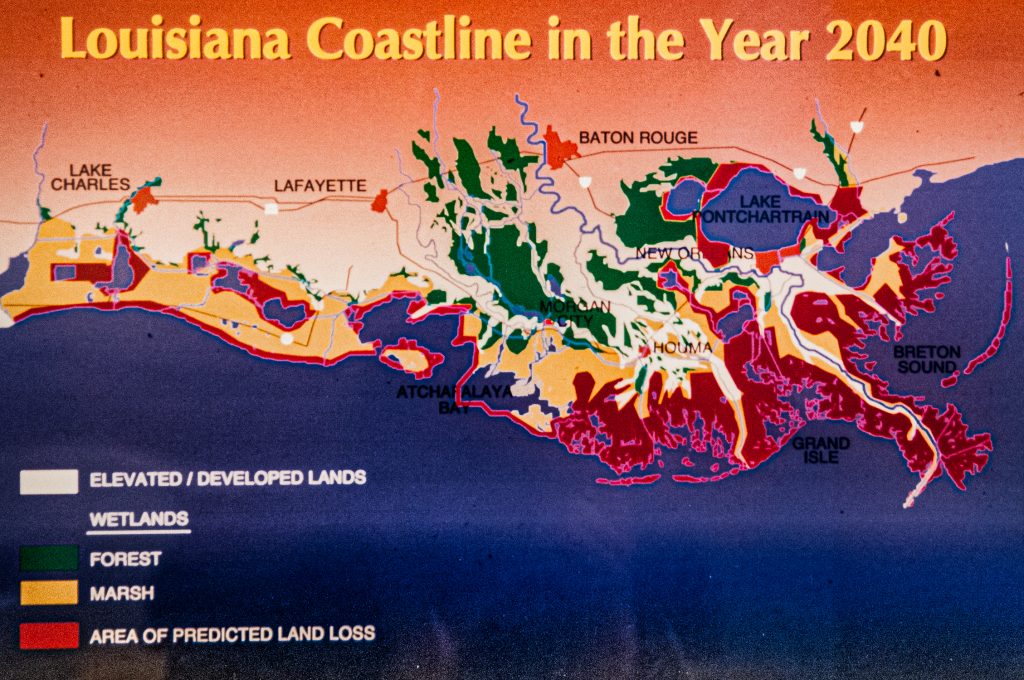

NWNL What is the importance of geology when evaluating hydrology, the delta, and the diversions?

PAUL KEMP Geology doesn’t stop. It’s always with us, and it will be in the future, even if we don’t see its changes from moment to moment. It’s important to understand geological processes, because a system like the Delta is not a two-dimensional system. It’s not just what you see on a map.

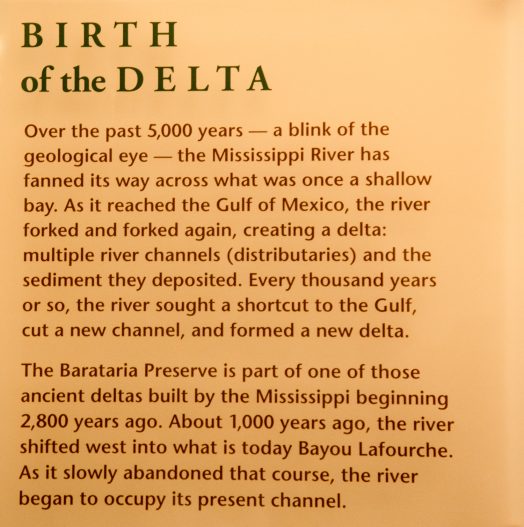

Depth presents a third dimension. What happens underground is critical to knowing what we’ll face if we continue along the road we’re on, and what we can do to change things. So, in a delta, geology happens a little faster than in other systems. Most people see storms affect beaches and barrier islands in even a matter of a day — or if a hurricane comes, in a matter of hours. It’s been “easy come, easy go” since 1975.

Potential loss and destruction is great, but there’s also potential healing from processes that build a delta. As we undertake restoration, natural processes that destroy the delta will continue, so we must offset them with building processes. We must ensure we don’t disrupt that healing process.

NWNL You should be writing the sequel to John McPhee’s Control of Nature.

PAUL KEMP Well, I’m very familiar with John McPhee’s Control of Nature, and his view of the hubris involved. I guess I’m guilty of that hubris by thinking we could reverse what seems to be inexorable destruction. The thing is that when John McPhee was talking about Control of Nature, very powerful natural forces were impinging on our built infrastructure of homes, buildings, and so on.

We think encouraging natural processes can be helpful, not damaging – especially considering the ability of the river to carry millions of tons of sediment and spread them into the Delta to build new land. That offers huge potential in confronting rising sea levels and global warming.

NWNL McPhee talks about man using infrastructure to change what nature does; and you’re talking about using infrastructure and marsh restoration to assist nature in what it does. That’s why you should write the counter sequel!

PAUL KEMP It requires a lot of audacity to direct nature to do our bidding. We’re saying to the river, “We’ve put levees along here, but we’ll give you a place to go. So, we want you to build land there, but not over here.” When we start to manage something as amazing as a huge river like this, it takes a lot of hubris. Many residents fear that, once unleased, this process will be unmanageable.

NWNL The new diversions are causing this fear?

PAUL KEMP That’s most of it. The idea is that we’d open holes in the levees and allow the river to build new channels away from the main stem, as it did in the past. That would restore both existing marshes, and then build new marshes and bays where there are none now.

I think of the delta as more of a process than a place. It’s like building a sandcastle. Every time the tide washes it away, you add more sand to keep your structure. But you must keep supplying it, even if you can’t stop the forces of removal. So, it’s a continuing process.

NWNL Two years ago on Mardi Gras, there was a breach in Mardi-Gras Pass, a man-made diversion along the Mississippi River in the Delta. This pass hasn’t yet been closed and remains a controversy. What happened then, and what should happen now?

PAUL KEMP On Mardi Gras Day, John Lopez, a geologist and Executive Director of the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation, was watching a part of the non-leveed east bank of the river. He noticed that a channel was making its way from the backside towards the riverbank.

We had a very high discharge the previous year when water flowed over this bank. It collected in the channel; ran out to the Bay; and gradually eroded over time. On Mardi Gras Day, 2012, it broke, and the flow began from the river to the bay. Before man tried to contain the river, this crevassing process happened countless times.

That channel has slowly grown, and it is now building land as it empties into the bay. The question is whether the USACE will come in and spend millions of dollars to choke it off – just as we create more outlets and get more sediment into the adjacent wetlands! So, there’s a lot of discussion about whether it’s a “navigable channel;” whether it was naturally formed; and whether it should have certain protections. It’s being watched very, very carefully.

PAUL KEMP Further down the river, the USACE built an artificial crevasse at West Bay. It’s in “The Birdfoot” where all the three distributary channels go out, about four miles upstream of Head of Passes. This crevasse was gradually becoming an efficient conveyor of sediment. In 2011 (a record flood year), new islands and new land emerged out of that bay. The channel became enlarged as it pivoted to a better position to convey sediment. The USACE, concerned it would cause shoaling in their dredged navigation channel, planned to close it off, even though they originally built it as a diversion channel.

Environmental advocates like myself, noting it was working as it was supposed to, stated it would be a real tragedy to close the river’s first serious artificial sediment diversion ever constructed. So thankfully, it is still open; building land; and not causing problems in the navigation channel. Everybody seems happy. From that, we’re learning how to protect early deltas from waves, and how to use wave-breaking islands to speed up the process of delta formation.

NWNL The Mardi Gras Pass captured my imagination, because it seemed like a mini replay of Mississippi wanting to jump into the Atchafalaya that we stopped. Could this Mardi Gras Pass become a significant natural diversion that the USACE would have to close because of all the infrastructure? How big will it become? Could it be eventually as big as the Atchafalaya tributary?

PAUL KEMP Since it’s pretty far downriver, it lacks the energy there is above Baton Rouge. As you go downriver, the head gets lower. But we could build a pass there, as a sub-delta that could get as big as Wax Lake. Now, as sea level rises and land elevation diminishes, we see more upstream diversions as more likely, with greater potential for surviving. We’re also seeing a diminishment in the flow through the channels of the “Birdfoot.”

NWNL Do you envision more passes? Maybe a Christmas Pass or Halloween Pass?

PAUL KEMP The physics dictate that will occur – unless we stop it. The river is essentially shortening itself as it faces sea level rise. It wants to get to the sea as quickly as possible. It doesn’t like unnecessary confinement en route. If we’d allowed it, the Mississippi would have already switched to the Atchafalaya Channel that is 200 miles shorter. We didn’t allow it to switch. [John McPhee chronicled this in his New Yorker essay, Control of Nature in 1987.] Now the only thing the Mississippi River can do is shorten up in position.

NWNL It’s a big puzzle, where the river seems to be trying to put the pieces together…

PAUL KEMP … while we humans experiment to see what happens if we shut off a major diversion. The river always expresses itself, in this case by retreating so that the mouth of the river moves upstream.

NWNL Paul, we’re trying to build diversions; but why can’t nature do it for us?

PAUL KEMP Nature can do a lot of it for us; but we want diversions that we can control. Otherwise, it would be easy – nature would take care of everything.

However, there are good reasons to control diversions, and even sometimes shut them down. For example, during seasons when fish come in, we must be careful not to turn the whole estuary fresh, which a big diversion would do. In our democracy, there are times when we have to make compromises. Likewise, we want to build land, yes! But we also want fisheries, flood control in the estuaries, and so on. So, certain times of the year we restrict flows, despite the river wanting to add more water into these diversions.

We can make structures that are effective in diverting sediment. We saw it on West Bay, where the USACE built a channel about 120 degrees from the river that forced water around a big bend. Although that was very inefficient for conveying sediment, the channel self-organized itself with a 90-degree pivot, becoming much more efficient.

We must learn what we should let nature do and how we might speed up nature, while not getting in the way. It’s so much less expensive to harness nature than to oppose nature.

NWNL I’ve heard very positive and very negative opinions about the future of the Delta and whether we can save what’s there now. Nobody thinks we can restore it to what it was; but can we save what’s there now? You optimistically said in the press and our last interview that the Delta is “self-healing.”

PAUL KEMP I also said earlier that all deltas are ephemeral. Their geology means they’re always changing. Land is simultaneously lost and gained. Deltas change with sea level rise, wave action and storms – and particularly with man’s reduction of incoming sediment.

NWNL This delta seems to present yet another upstream-downstream issue….

PAUL KEMP Yes, upstream farming used to increase downriver flows of sediment. Now our many dams reduce that sediment from reaching our oceans, thus deteriorating deltas. It’s a simple balance of how much comes in and how much erodes away or sinks. We’re now trying to get more fine-grain sediment back into the river.

Sediment used to flow down from the Missouri River’s Great Plains area, primarily via the Platte and Kansas Rivers. Not as dammed as much as the Upper Missouri, they still are dammed enough that the Missouri River’s sediment is greatly reduced. But, if we can change our management of those two rivers, we can probably double the sediment coming downriver. I don’t know how easy or hard that is, but I don’t accept only having that trickle of mud we get downriver now.

NWNL I feel Louisiana is the poster child for climate change, for subsidence, for delta issues, and so many other issues. This morning Brian Piazza (with the Louisiana Nature Conservancy) said, ” Because the Lower Mississippi is such a ‘working lab’ on the edge, we’re the ones coming up with the innovative solutions that the rest of the world can model, follow, and maybe improve on. But we’re beginning the process.”

PAUL KEMP We’re kind of in the middle of this process. It began a long time ago for us.

Alternatively, we can pump sediment here and there, but it will be impossible to pump the huge volumes required. What the river can do easily requires huge amounts of fossil fuel for us to do! So, we should do what the river can’t do itself, leaving a system that can maintain itself without continual infusion of fossil fuels. We already have dams and spillways that work quite nicely without huge amounts of pumping.

Having watched deltas emerge out of the water as a flood recedes, I’m always struck by the amount of organization that’s there, and how quickly new land can be created. That gives me hope. We just need to get man out of the way so that river can go back to what it knows how to do: build land, produce fisheries and establish habitat.

In some cases, we need technical solutions to work around human infrastructure. I think our challenge is to build restoration infrastructure that doesn’t require a lot of energy to maintain. We should build diversions operated by gravity to regulate flow.

NWNL Is the Mississippi River Delta still capable of being a self-healing unit?

PAUL KEMP Its processes are determined by the physics. The physics don’t change; but sediment amounts and sea level rise change. So, the delta of the future will be some balance of all those things. There will still be a delta here, even if we don’t “turn the tide” in my lifetime. It may be much smaller and much less capable of supporting human activities and cities; but there will always be a delta at the end of the river. So, yes, it still has the potential to be self-healing – if we let it.

NWNL In our 2011 interview, you said management of the Delta and Atchafalaya River Basin was geared to benefit bureaucracy. What did you mean by that?

PAUL KEMP Every day of the year, we only allow 30% of the combined flows of the Red and the Mississippi Rivers into that Basin. We don’t know why 30% is the best. The best for what? We don’t know. So, we stay at that ratio set by bureaucracy because the alternative is to negotiate to apply proper science with the users.

NWNL Let’s chat about the Bonnet Carré Spillway that I photographed today. What is its purpose? How effective is it today? How often is it used?

PAUL KEMP Upstream of New Orleans, the Bonnet Carré Spillway is a 2.5-mile-wide part of the east bank of the Mississippi River. Not really gates, it was just pins-and-timbers, built in the late 1930s. When the river is high enough to move New Orleans’ gauge up to 17 feet, they start pulling out these timbers so water overflowing the riverbanks can move into the spillway behind Bonnet Carré.

After those floodwaters flow through this spillway for about 5 miles, they spill into Lake Pontchartrain. It works very well in taking pressure off levees downstream along New Orleans. It also diverts and deposits some sediment and sand into the spillway which is sold between openings of the Bonnet Carré Spillway to folks in New Orleans who need to raise their lots.

In its 80-year history, it’s been opened ten times, I believe; but five of those times have been in the last 40 years. It’s being opened more frequently now, probably because climate change causes more frequent high-discharge events. But that hasn’t been verified.

NWNL Are there any negative side effects to opening the Bonnet Carré Spillway?

PAUL KEMP Each time it’s opened, a fair amount of sedimentation gathers on the bottom of the river just downstream of the Bonnet Carré. The flow through this structure can be 300,000 cubic feet per second. With such a big flow, sediment doesn’t move at the same rate as water. Thus, a lot of sediment is left in the river, forming bars on the bottom. However, with each flood event when the Bonnet Carré stays closed, more and more sediment is swept downstream. Thus, opening and closing these structures doesn’t cause bad shoaling in the navigational channel, because there’s enough energy to move the sediment.

NWNL On an average day like today, the Bonnet Carré looks like little spindly sticks – unlike the Morganza Gates, which I just photographed. Is this structure strong enough to withhold a strong Mississippi flood that is not extreme enough to warrant opening the spillway?

PAUL KEMP Yes. Since it’s a very simple structure, it leaks some. But that’s okay. It’s worked very well for 80 years – almost a century – which shows what it can do. There’s no reason it won’t work for another century. We don’t necessarily have to have very complicated structures; but we do have to have reliable ones. Reliability usually goes along with simplicity.

We want structures to be as simple as possible and not need complex mechanisms. Our Flood Control Authority is that dilemma now with a gate that is very difficult to manage and operate. When a hurricane is still three days away, we must close the Intracoastal Waterway on the north end of the barrier you saw. We must pull a floating barge onto some pins and sink it in place. It’s just too complicated to be reliable; and this gives me a lot of appreciation for the virtues of simplicity.

There’s a lock and a gate there that we must close when a storm is coming. It has turned out to be one problem after another. We worry about whether it’ll function properly under severe conditions.

NWNL Paul, do you still have a car with roll-up windows?

PAUL KEMP No, but I remember that in my first car with push-button windows, they weren’t that reliable.

NWNL Courtesy of South Wings, I photographed Lake Borgne Inner Harbor Navigation Surge Protection Barrier this week on one of their pro bono conservation flights. Although this infrastructure hasn’t yet been tested, would you recommend it as a good model for other coastal cities, such as New York City, Philadelphia or Boston?

PAUL KEMP Well, it will be certainly held out that way; and there’s every reason to expect that it will work. This Navigation Channel Surge Barrier is one of the most ambitious flood control structures built in North America. It’s not really that spectacular compared to some European structures, but for us it’s quite sophisticated. At about eight meters high, it’s designed to take the full brunt of a surge and to be overtopped in an emergency.

This barrier is probably the strongest point in the whole East Bank New Orleans Flood Protection System. It’s also the most expensive part. Initially, they discussed raising earthen levees with flood walls along both sides of the MRGO funnel. Those ideas were discarded, because their performance could not be assured, given our soil conditions.

We had destroyed the naturally protective, marsh apron out in front of these vulnerable places, so a stronger protection system was needed. This need to create such a brute structure against the force of nature is a sign of our failure. We’re not working with nature at all, and actually we’ve destroyed nature. John McPhee addressed this in his Control of Nature. We’ve insulted nature tremendously; destroyed the marshes that once formed a buffer; and now we’re trying to replace nature with a very expensive structure.

NWNL This is our mea culpa.

NWNL Here’s a multi-pronged question. You noted three years ago that people detached from their rivers can’t understand that the Mississippi River needs its floodplains. Is there clearer awareness on this today? Are we better communicating the need to connect people to the floodplains and floodplains to the river?

PAUL KEMP I think public awareness has increased in some ways. But neither public understanding nor science is much further along. Concerns about other things easily take precedent. New Orleans has huge problems with education, crime, and so forth; and even though they damage the city, they’re not likely to destroy it in just one day. Yet a failure of the flood-control system would. Sadly, many day-to-day problems take precedence over those rare events that are catastrophic.

Every day, all emergency managers struggle to keep the image of total destruction in people’s minds, as it needs to be. Many in New Orleans ride along a levee or flood control structure, without knowing what it’s for. As well, they may drive through a flood gate but never notice or ask, “Why?”

NWNL What’s the solution to that?

PAUL KEMP When I was working with NGO groups, our main purpose was to raise awareness of the need for restoration and the fragility of living in a delta. For us to succeed in restoring this delta, we need enthusiastic and impassioned support from residents. We don’t have the time for anything more gradual. Lawsuits create perspective and can quickly gain funding for restoration when there’s no other plan in sight. But too often, that’s seen as greedy lawyers trying to usurp the power of the state.

The scientists who understand what we really face have a sense of desperation; but most people don’t. The way these decisions will be made is family by family, and they’ll be made after the next storm. It’s not a corporate decision.

NWNL What can one person do? What decisions can the average person make now?

PAUL KEMP The average person can demand flood protection and flood resiliency be at the top of all politicians’ lists. It amazes me that Mayor Landrieu rarely talks about flood control or the next hurricane. Of course, people want to forget about that; but, like going back to sleep, that doesn’t change the outcome.

NWNL I first visited New Orleans 15 years ago to photograph musicians in the French Quarter. Now I’m back, focused on water issues. I attended a Society of Environmental Journalists’ bus tour, but the driver couldn’t tell us what body of water we were crossing! Then, crossing the city in a rental car, I noticed there are no signs identifying the lakes, rivers or bays.

PAUL KEMP Yes, you are right.

NWNL Signage is such a simple way to raise awareness, but so seldom used. In 2008, I interviewed an activist in British Columbia who posted his own signs along the Columbia River to educate people. Why isn’t the City of New Orleans or its stewardship groups at least creating signage?

PAUL KEMP Great question. I was Vice President at Audubon, but the idea of signage didn’t really strike me as important. We put up some signs where major breaches happened during Katrina, but they were quite controversial. People didn’t want them.

NWNL I understand resistance over negative messaging; but what’s wrong connecting people with the names of waterways at each bridge? Folks campaign about “MRGO’s Got To Go,” but what does that even mean to those who don’t know what or where the MRGO funnel is? Education is necessary to achieve the passion you want.

PAUL KEMP Right. We haven’t been successful yet.

NWNL You’re concerned today’s New Orleans population can’t fiscally support the infrastructure protection the city needs.

PAUL KEMP Well, it needs to be a much higher priority. In the Netherlands, flood plain management is top priority. All else comes out of that and puts people into self-reliant groups. With a very long history of democracy, the Netherlands organized its plans around these drainage systems and that structure extended into their whole government.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: Seventeen years after this interview, and following Hurricane Ida’s floods in Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey and New York that killed over 110 people in 2021, The NY Times (9/7/21) published To Avoid River Flooding…,” discussing The Netherlands’ very successful Room for the River Project.] A city like New Orleans needs to be organized so everybody knows where their water drains, where the threats are, and how they can tax themselves to improve things.

NWNL In 2011, you told me we’d reached the Age of Sustainability. Now, three years later, are we closer to that sustainability? Are we more safe or less safe now?

PAUL KEMP I feel New Orleans’ flood protection is much better than before Katrina. Our threat now is increasing storms that exceed Katrina’s damage. We need to inform people that climate change means bigger storms, and a need for greater flood protection systems. The levees will not stay put, and must be continually maintained. We always need to be improving our flood protection. We can’t just sit on a deteriorating system. From Day 1, the system is always degrading.

NWNL Before Katrina, you said, “The New Orleans levee system is more papier maché than reality.”

PAUL KEMP Well, now we have a very capable flood protection system, but its maintenance requires huge investments. If we don’t continually seek out weaknesses and ways to improve that protection; then 10 years from now, we won’t have the protection we think we have today.

NWNL You’ve also said, “The Louisiana Coast is a working coast in which the environment is pretty much taken for granted.” Is it still; and if so, should it be wilderness?

PAUL KEMP Yes, it is a working coast – for oil and gas industries, coal shipment and fishing. Louisiana has a unique culture because of its association with the Delta. If we tried to entirely exclude people and their activities from the Delta, then we’d have lost something just as valuable as the Delta. We’d lose a heritage that has brought many unique aspects to America. We need a balance that ensures a potential for survival.

NWNL What would you like to tell me has been achieved when I come back five years from now?

PAUL KEMP Well, if I’m still on the Levee Board, it will mean we succeeded in keeping our lawsuit for fiscal settlements alive and that we’re funding coastal restoration at a much higher rate than we are today. That would be my best dream.

NWNL Thank you, Paul. I hope your dream to restore the Delta succeeds!

Cypress marshes were Nature’s protection in the Delta, before oil/ gas industry impacts, loss of upstream sediment, sea level rise and more intense hurricanes.

Posted by NWNL on September 11, 2021

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.