Saving Mountain Caribou

Columbia River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Columbia River Basin

Pat Field

Fish & Wildlife Habitat Biologist, Consultant and Stone Sculptor

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director and Photographer

On our 2007 Columbia River “Source to Sea” Expedition, Pat shared his sculpture and discussed conservation with me. He described the new Darkwoods Conservation Area as a rare chance to protect the Kootenay’s rare inland temperate rainforest and its species. His Darkwoods story is a great model for saving disappearing ecosystems and endangered species, such as mountain caribou!

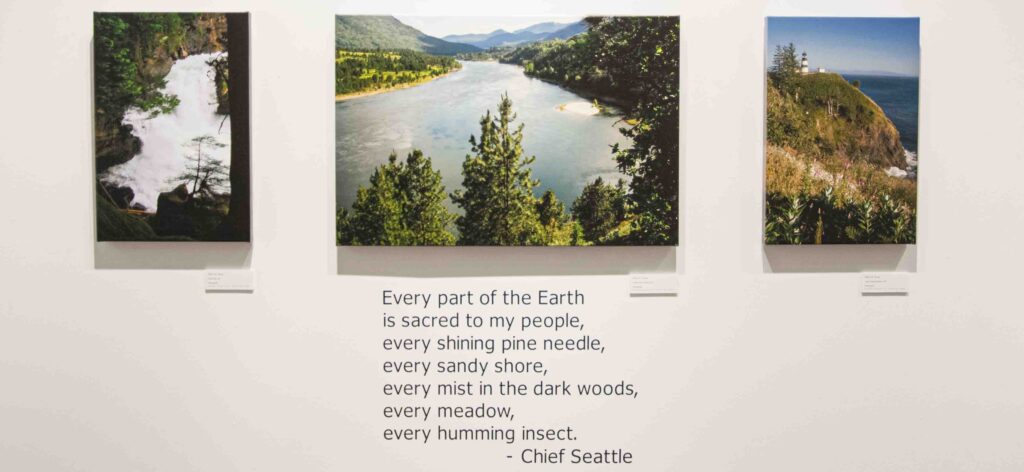

His wife Val, Director of the Kootenay Gallery and focused on river-oriented art, offered to exhibit NWNL photos in 2008. That chance created a great reason to return to Castlegar and further focus on the vast Columbia Wetlands — and to open our first NWNL photo exhibit.

A SENSE of PLACE on the COLUMBIA RIVER

ART, SCIENCE, CONSERVATION and PEACE

DARKWOODS: WATER, CARIBOU, GRIZZLIES

SPECIES PROTECTION = WATER PROTECTION

DARKWOODS INTERTWINED BENEFITS

FIRST NATIONS & DARKWOODS PROPERTY

ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT ISSUES

SOLUTIONS IN GOVERNANCE

FRESHWATER THREATS

NATURE CONSEVANCY of CANADA

FISCAL SOLUTIONS to CONSERVATION

CONSERVATION & ART

MOUNTAIN CARIBOU

CONCLUSION

All species, whether plants, fish, or mammals, are self-replicating packages over time and produce a diversity that affects the ecosystems they live in. But if we do not have the connectivity of genetic diversity, then we lose that opportunity over time to be resilient and remain productive. – Pat Field

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

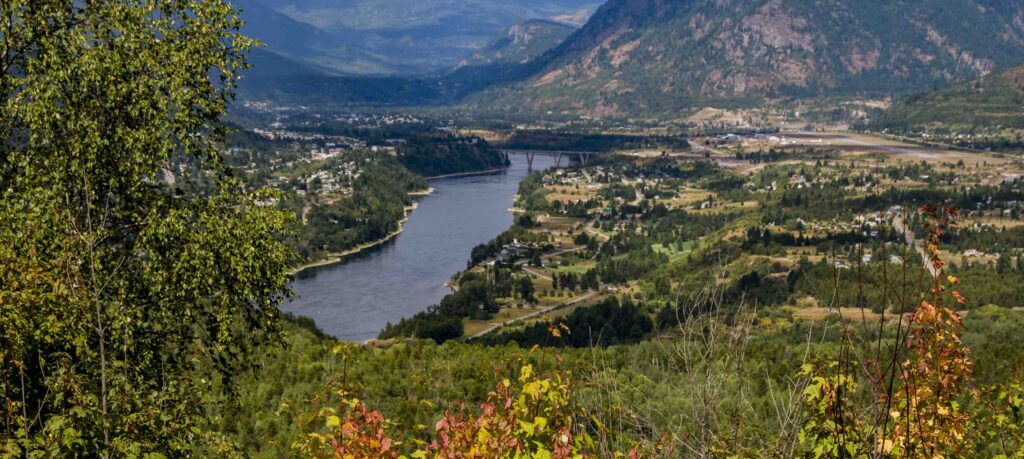

PAT FIELD I am a citizen of the Columbia Basin, now living in the northern portion of the Columbia Basin in this wonderful community of Castlegar. For 15 years we have lived here at the confluence of the Kootenay and Columbia Rivers, one of the last free-flowing portions of the Columbia. Within this Columbia River system, I have worked as a Conservation Officer, a Fisheries Biologist and Planning Assessment Manager. Provincially, I’ve been intimately involved with the Species at Risk Policy. My new job is working for the Nature Conservancy of Canada as Project Manager on exciting project in the Kootenays.

NWNL Living right on the Columbia, you and Val certainly seem, each in your own way, to be motivated by the significance of this local stretch of free-flowing water on the Columbia. What makes it so special?

PAT FIELD As I look out my front yard, I first see the still mountains that surround us and then something moving underneath it. I sense the context of this landscape as it was several hundred years ago. These systems are now completely changed by today’s reservoirs. Nutrient regimes have completely changed. Processes have slowed. The salmon aren’t here anymore. Nutrient cycling in riparian areas has completely shifted. So remaining free-flowing portions of the river are very special. There are certain species in those free-flowing areas that spawn only in fast water. That’s important to remember as we try to protect those places.

NWNL Can salmon populations reproduce here, above the 49th parallel?

PAT FIELD Salmon reintroduction is a dream of many, both First Nations and others who want to put salmon back in the Columbia. It would be very difficult technically; but we can overcome this adversity. Our issue now is to address prosperity issues involved in returning salmon back into the system. To our west in the Okanogan, efforts and trans-boundary collaboration are going on to get salmon back in the Okanogan system. It is possible. We just need to go after the dream and do it together. There are significant genetic issues involved, but technically it is possible.

NWNL You talk of “genetic connectivity.” How do you define that?

PAT FIELD To me it means that all species, whether plants, fish, or mammals, are self-replicating packages over time and produce a diversity that affects the ecosystems they live in. But if we do not have the connectivity of genetic diversity, then we lose that opportunity over time to be resilient and remain productive. So, it is important to connect on several scales. Landscape-level connectivity could be in areas of several million hectares, or ½ million hectares, or even down to10 hectares – any of which could ensure that local species can move and connect with other populations of the same species, thus maintaining the diversity that allows those species to remain resilient. That way they can keep their ecosystems functioning, because each species has an effect and a functional role in the ecosystem.

NWNL Why do you see a “sense of place” as a motivator for conservation?

PAT FIELD I have a long history about caring for the environment and many discussions with friends, colleagues and acquaintances about why they care about their neighborhood, their community. I am interested in what has connected them to nature that makes them want to participate, engage and act on their concerns. For me, that’s comes from being connected into the place where you live. Those of us in the Columbia River Basin have a sense of place. We are grounded here and most of us want to live and die here. We want to be a part of this system; and the only way we can protect it is to fit into our neighborhoods, our communities and our political society. And the only way you can get to know a place passionately is to touch it, feel it, smell it and be a part of it, be connected to it. That’s how to encourage engagement in conservation issues.

NWNL It seems that by forging your interests in nature and sculpture, you achieved an even greater impact than if you pursued only one or the other.

PAT FIELD I’ve been involved in the science and bureaucratic worlds for 30 years and in the creative world for 30 years. Given my need to experience nature through perception, intuition and motivation, I’ve found art is a great way for people to become still, aware and in awe of what goes on. Emotional triggers are what get people to act. When they walk in their community along the river, or see an osprey nest, or just sit there, they are basically speechless. They are in awe. They don’t have to think anymore, so they get connected to it.

At the same time, we need science show us the consequences of our actions. So we need science to motivate artists, and artists to motivate scientists to recognize we are emotional animals, affected by things that we hear, touch, taste and smell. That’s how I connect with nature. Hopefully, my art brings people together emotionally, so they want to do act, not in a negative sense, but to have a sense of wonder and awe about being a part of it.

NWNL While sitting here on your “conversation bench,” please explain how you use artistic efforts to support ecosystems and watersheds?

PAT FIELD A couple years ago, I and other sculptors attended a water symposium here. We dreamed of developing a “conversation bench.”. We asked many artists around the world to send us a little stone from their favorite stream, explaining why that stream was important to them, their families and their communities. Those stones were brought here and embedded into pewter and bronze and then into this massive 5 x 5 x 18’ wooden bench. We formed it into a very organic shape, as if a log in the river. Our concept was somebody from Israel could sit on the bench talking about water’s importance to them while somebody from the Columbia River could be on the other side of the bench talking about their issues – two completely different conversations full of passion on the importance of water for life. It worked! Now we’re donating that bench to the Near Peace Center at Southbrook College.

My philosophy is conservation can promote peace by using art and conservation as a level playing field. We must encourage people from all cultures, races and religions to come together to work on something that’s positive, constructive and addresses issues without alienating them. To me, that’s powerful.

NWNL I am interested to hear about your part in conservation efforts occurring in the Darkwoods property! Where in the world is Darkwoods – in just the southern Selkirks, or across all the Columbia Mountains? Most importantly what is its significance?

PAT FIELD Darkwoods is private property recently purchased by the Nature Conservancy of Canada. It lies in the South Selkirk Mountains in a triangle between the Community of Creston, the Community of Nelson and the Community of Selma. It is 55,000 hectares of contiguous property, adjacent to the world-renowned Creston Valley Wildlife Management Area. The Mitch Creek Wildlife Management Area and West Arm Park, creating a contiguous conservation area over 100,000hectares. This is significant because it provides opportunities for whole ecosystems with intact predator-prey relationships. By that, I mean grizzly bears, black bears, cougars, wolverines and their prey – deer, moose, elk, rabbits, ground squirrels – living in harmony in a large enough landscape that they can adjust to human pressures and other non-anthropogenic effects, like climate change. The significance of the Darkwoods property is that it goes from the valley bottom up 500 meters to the lake, and to 2,600 meters in the alpine region. Given our limited current knowledge of climate change impacts on species, Darkwoods provides great opportunities for wildlife to migrate elevationally and horizontally through other landscapes. This is unique since it’s the single largest conservation purchase in Canadian history. We are on new ground here, and it’s exciting because it’s a working landscape, not a park. Our job is to find ways to have economic and recreational activities driven by conservation objectives on the property.

NWNL Back to water resources and snowpack, how does available water in Darkwoods affect its flora and fauna, including endemic and endangered species, caribou, bull trout and ancient stands of trees?

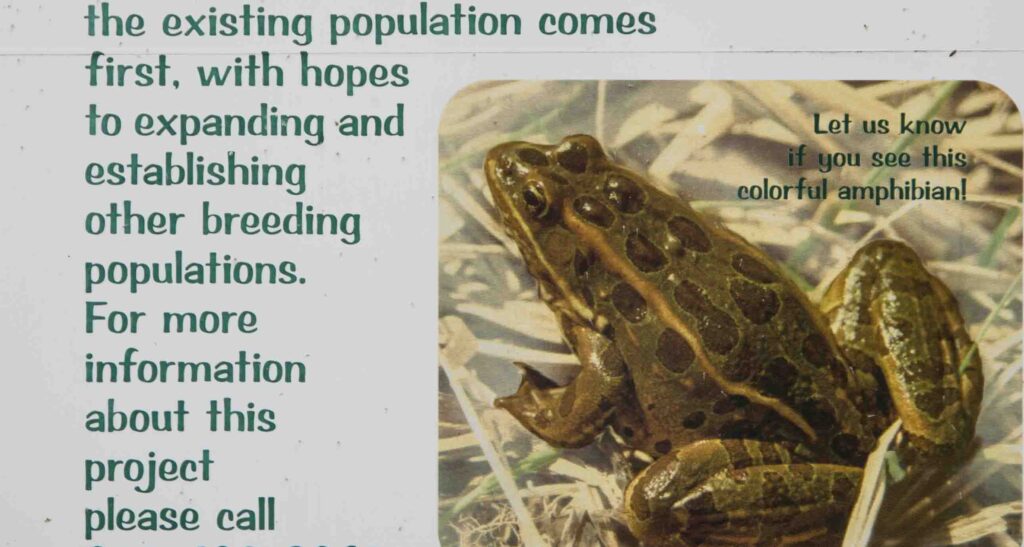

PAT FIELD There are many values on the Darkwoods property that are important to conserve, protect or restore. Its diverse set of ecosystems range from those that are very dry to wetlands. So potentially we have habitat to support species like northern leopard frogs on a very small portion of the property, right up to alpine species and everything in between. The terrestrial vertebrate populations include ungulates, like deer, moose, elk, mountain caribou, mountain goats to smaller animals like marmots, ground squirrels, cavity-nesting birds, dragonflies, moths, both endangered and common plants – a huge diversity. Over 13 different tree species grow on the property creating a very diverse ecosystem.

Potentially, there are enough kinds of habitat to support 29 at-risk species, 9 of them now nationally threatened. We know the habitat is there, but need baseline information verifying the species’ locations. Right now, we are supporting the southern-most population of mountain caribou. Over half of Darkwoods’ 55,000 hectares is mountain caribou habitat; and only 46 of them are left in the southern Selkirks. This is the only trans-boundary territory where our animals can enter into the U.S. Mountain caribou have been endangered in the U.S. for decades.

In British Columbia, we’re developing a Mountain Caribou Recovery Plan. Without this Darkwoods piece of private property, the mountain caribou would become extinct because Darkwoods holds a significant portion of their habitat. Given their life requisites, they need this piece of property conserved. Part of our Darkwoods mission is to provide habitat for these animals.

We also have a significant population of grizzly bears on the Darkwoods property that are part of a Grizzly Bear Recovery Strategy in the U.S. They are a top-end predator in the ecosystem That position in the species trophic cascade links them to all underneath them from Clark’s Nutcracker birds to Columbia ground squirrels.

What’s great about this piece of property is its intact predator-prey systems. If you consider a global North American context and the shrinking ranges of ungulates and predators, B.C. becomes very important. Within B.C. the Kootenays are important; and within the Kootenays this piece of property is significant. I feel privileged to be a small part of trying to develop an appropriate management plan that will include economic opportunities on the property and be driven by conservation objectives. It’s exciting to be part-and-parcel of learning how to best support caribou, grizzly bear and other populations. It’s critical that we get community support for activities on the property.

Like most human endeavors, it takes time for people to get together on the same page. Our challenge will be working with people. To manage species, we must manage human behavior. Our task is to excite and motivate people in the community about these species and the value of Darkwoods in supporting their quality of life. It’s not just about animals. It’s about the water, land and fish species we have, from bull trout to rainbow trout and cut-throats. The Darkwoods property has over 17 third-order watersheds, including larger watersheds with no extractions. There are no community or domestic watersheds on the property with extractions for human consumption. That is significant because all the water flows into Kootenay Lake or the Salmo River. There are not too many places in the free Western world where this happens. So, we provide a level of ecosystem services to our communities, providing a quality of life so other species can live out their life.

NWNL Darkwood protects mountain caribou habitat, and its 17 watersheds protect freshwater resources. Given our NWNL interest in freshwater availability, quality and use, Darkwoods Conservation Area seems to be a great example of protecting freshwater resources by protecting endangered species.

PAT FIELD It’s exciting to produce a Management Plan by conserving or protecting habitat for terrestrial species, such as mountain caribou or grizzly bears. And yes, simultaneously, we’re providing opportunities for abundant, clear, cool, continuous water supplies for freshwater species and downstream ecosystem services for people’s human water consumption, irrigation, and electricity needs. It’s neat that by protecting an old-growth forest for mountain caribou, with lichen that they feed on, you also are protecting riparian areas. They had old cedar and hemlock stands that filled out life requisites for 90 species of critters depending on old growth. Those species include cavity-nesting birds, fish in the streams and more.

The linkage of caribou to water is a fascinating story. To protect caribou, we’ll conserve a large portion of old growth that remains on the property. That old growth is in the high elevation with arboreal lichens that caribou feed on and in the valley bottoms with riparian areas which are migratory corridors for many species that move elevationally up and down the property. Darkwoods also provides tree shade to keep the waters cool on the property. It provides large organic debris that continuously falls in the creeks, providing habitat for invertebrates and fish species.

This property is as simple or as complex as you want to make it. You can a directly link one species with a functional role in the ecosystem to many other species. We propose to use the knowledge we now have on species’ key ecological functions and their habitats to discover how many other species could be protected by using a focal species to protect. Caribou is one of those.

We hope to develop a story on what we’re doing, why we’re doing it and we’re linking aquatic resources with terrestrial resources, because we don’t do that very well. Everybody is a specialist in the science world, but landscapes aren’t just about animals or fish. They are about connectedness. We need to generate those stories. It’s not about atoms, it’s about how we talk and commune and connect.

We think we now have a game plan to create those stories since we have some great information out of the U.S. around functional roles of species tied to structure and ecosystems. On the Canadian side we have excellent mapping standards. So, we plan to tie together those sources of scientific knowledge: species information, ecosystems’ structure and function, and our mapping and classification system.

Because this area is so large, we can’t know every place, where or when. We must use scientific processes like modeling to give ourselves some confidence in conserving ecosystems to be productive and adaptable over time. These things change as a result of time.

NWNL Is there a history of human usage of the Darkwoods property starting with the First Nations? Did logging take its toll here?

PAT FIELD I feel it would be arrogant for me to say I know what the human history is on that property. Before this land was settled by white people, there was a long history of the K’tunaxa First Nation living in this territory for 10,000 years. There are pictographs on the property; and we know there was also traditional use of the property, from hunting and berry picking to ceremonial services and vision quests.

Europeans started settling in the Kootenays in the mid to late 1800’s. In 1897, a Crown grant from the railway was given for private use. This property was originally a Crown grant owned by several different operations up until about 1960. They either logged, mined or trapped the property as values on the landscape changed over time. The first people were trappers on the property trying to find passes over to what was then the Salmon River, now called the Salmo River.

Then miners moved in, attempting a successful operation on the property. Forestry operations started in the 1930’s and 1940’s. Up until about 1960, 5 or 6 logging companies owned the property; but they weren’t successful. In 1967, a German royal family purchased the property to manage it with a German philosophy of seeing the whole estate as a landscape. They tried to put a sustainable forest operation on the property with infrastructure throughout the whole property and harvesting based on economic and conservation objectives.

In 2008, that family sold it the property to the Nature Conservancy of Canada to be operated sustainably and kept with its ecosystems intact. It has been a privilege to work with this owner, and it means we didn’t have to start from scratch. There are many restoration opportunities on the property; but it’s not all about restoration. We have intact ecosystems we are working with, learning from and using as reference ecosystems for others outside this property facing similar threats that need to be restored. Thus, Darkwoods offers reference ecosystems. Its history of use is now a benchmark, a starting point from which to develop conservation objectives that will drive future economic and recreational opportunities on the property. This is unique opportunity.

NWNL Beyond Darkwood’s importance to endangered caribou, ancient stands and bull trout, what significance do you see regionally, provincially, nationally and internationally for this conservation effort?

PAT FIELD This property is 55,000 hectares! How big is that? Our analogy is that it’s 9 times the size of metropolitan Vancouver, our largest community in British Columbia. It’s 140 times the size of Stanley Park, the biggest urban park in our province. Yet it’s much smaller than many National Parks in the province. Because it goes right up from the lake bottom to the mountain tops, it offers a unique elevational gradience that allows species to adapt their habitats to other elevations over time. This unusual situation will allow them to adjust to climate change more easily. That is significant.

In a regional context, it’s linked to other properties currently being managed for conservation. The world-renowned Creston Valley Wildlife Management Area has over 100,000 migratory birds on it. The Midge Creek Wildlife Management Area is setting conservation objectives. The West Arm Park is adjacent to the Air Proctor Community Forest which is being ecologically harvested in a sustainable manner. Additional regional significance includes the fact that its 100,000 hectares provides sufficient home ranges for grizzly bears and other predators, thus maintaining whole ecosystems.

In the context of western North America, Canada’s rangelands for a number of ungulates and predators are contracting. So, British Columbia is becoming more important nationally and internationally. For us, this one little property becomes internationally significant, because we host a habitat for a threatened population of mountain caribou, endangered in the U.S.

One measure of Darkwoods’ international significance, is that there are 1,900 animals left on Planet Earth associated with mountain caribou. Our subpopulation of 46 animals has the potential of being recovered. Darkwoods will test whether we care enough to do this. Our job is to supply the habitat for those caribou. The province mandates that we manage the caribou population. We want to do our part and to collaborate with other partners to ensure this property provides habitat for our old-growth ecosystems.

We are looking at a wide scale: from protecting one tree and one little old-growth stand, right up to the international significance of providing ecological services for water, fish species, temperate old-growth rainforest habitat, mountain caribou and landscape productivity for a threatened grizzly bear population. Also, Darkwoods contains many other species in its low elevations, adjacent to the Creston Valley Wildlife Management Area, that we have yet to tap into, like Northern Leopard frogs.

NWNL Pat, besides the unique significance of managing and protecting Darkwoods ecosystems and species, there also seems to be an unusual opportunity for sharing your experiences here with others as well as learning from others. Do you sense that back-and-forth synergy in your work?

PAT FIELD Darkwoods is exciting because we learn something new every day that we can share with others who then can help us figure out the ways forward to keep these ecosystems productive and adaptive. We’re working to give our species the best opportunity to replicate and have a functional role in their ecosystems. If they stay productive, we can continue to have some sense of quality of life and get some services off those landscapes.

NWNL What threats do you face or anticipate, from human impacts to climate change?

PAT FIELD Indeed, there are threats to the ecosystems and species that live within those ecosystems. There are many anthropogenic effects (i. e., human effects) affecting our efforts. For instance, for the last 100 years, British Columbia has had a fire suppression policy, causing ecosystems to change over time. In some stands that traditionally had fires every 10 or 12 years, they haven’t had fires for a century, which has certainly changed those ecosystems. We’ve logged the property now for 60+ years. So, while it was managed sustainably for economic purposes, new logging roads and patterns of that landscape certainly affected the property.

The over-riding threat is basically from human behavior, especially resource extraction such as subsurface mining and recreational activities on adjacent lands. People want to snowmobile, cat ski, heli-ski, mountain bike, fish, and hunt. One of our challenges is to understand what the limits of allowing human behavior to alter our landscapes over time.

Species interaction is an ecosystem challenge we don’t yet fully understand. Predator-prey relationships present complex scientific questions we’re just starting to answer. Many predators eat prey; but sometimes, while caribou are not a primary prey, they get eaten by predators.

Also, there are human impacts from outside of Darkwoods that involve predator management. Mountain caribou biologists say the immediate cause of caribou deaths is they are being eaten. What’s the right thing to do? There are split opinions about our biological role. To recover populations in the short term, we must understand how to manage all species, including all the predators.

Climate change poses other threats on the property that we can’t control. But we can try to provide the best opportunities for species to be adapt over time while we learn about climate change and management practices we could change in order maintain productive ecosystems. This property offers significant opportunities to address climate change as it includes terrain from the lake to mountain tops. If low-elevation tree species are going to move higher over time, maybe we should transfer trees to higher elevations now – in advance of catastrophic climate changes – including increased beetle populations, underground fungi or threats we don’t yet know about.

While we can address many threats, individually we don’t always feel able to control issues like politics. In a democratic society, if we care enough, we can create policy opportunities outside the property. On Crown land we can create solutions and seek economic opportunities to support our quality of life, spreading that beyond the property. But without functioning ecosystems and species with functional roles in those ecosystems, we’ll end up with much simpler ecosystems and more dramatic events. We can now put some clear outcomes-based objectives into motion. We’ll start monitoring and determining whether the direction we’re going will get us there and make some changes along the way. Our political will can help protect and restore mountain caribou on crown land and let us face other threats to the property. Citizens in our own communities can influence support for conservation – not just people who work on the property. So, part of our outreach program tries to create awareness that protecting our land and water is important for our communities in the long term. Our grandkids and future generations should have the same awe, wonder and available resources as we’ve had. We must ensure these benefits continue for them.

NWNL How do those threats you enumerated impact freshwater issues?

PAT FIELD The property up at 2,500 meters sometimes has 9’ of snow that can last into June and return in October. So, for 8 months of the year, there are no people on the property. That watershed snowpack ends up in the 50 lakes on the property or its streams. It provides a cold, clear, abundant and continuous source of water into the Kootenay Lake and Salmo River systems. That’s important because our activities on this landscape affect how that water is stored and released on the property. Our forestry, road building, harvesting and cultural practices, tree planting and riparian-area protection are integral to our connection with the landscape and human activities. They all create downstream consequences.

We are just now starting to make upstream decisions in linking fish in the river with how our upstream activities affect water quality and quantity, flow timing, temperature and discharge, plus aquatic invertebrate production. It’s important to tie all these things together. We must focus on wholeness and connectivity.

Watershed management, like conservation, isn’t just about one little thing, one creature, or one person’s vision of what should happen. It’s about keeping the whole landscape functioning. That is what’s exciting. This is a personal rebirth for me, because I learn new things every day from other people with either a tidbit or a grander scope of experience than I’d ever imagined. They share stories about how we can do better and how we can contribute. To me, that is pretty neat.

The Nature Conservancy of Canada [NCC] is a leading non-profit, non-advocacy, non-government group that owns the Darkwoods property. As a national organization, it works with private property owners to purchase or develop covenants and land arrangements that will conserve inherent landscape values. Their Darkwoods purchase is their crown jewel and the largest single purchase in Canadian history. It sets a new benchmark towards their purchasing larger pieces of as the best opportunities for whole ecosystems to become resilient and adaptable over time. The larger the property, the better we can maintain those ecosystems, and all their species. Having said that, many of their smaller properties are purchased for significant specific values that are very important as well.

NCC helps landowners conserve properties. They don’t create parks, but if they buy ranchland property, they’ll work with the ranchers to create a working legacy for conservation on the property, while they continue to work as before, in a sustainable manner.

As well, NCC offers a working solution concept and working landscapes. I applaud its use of science to drive understanding and inspiration for citizens and communities to understand why species and ecosystems are critical to Canadians’ quality of life. Darkwoods has a great opportunity to develop a longer-term and larger property legacy for future generations. Ensuring ecosystem services through water and land resources will provide economic and recreational opportunities in perpetuity.

The Canadian government has recognized the significance of this program’s natural-area conservation plan and its ecological gift. They have given NCC $225 million over the next 10 years. Using a scientifically credible planning process, NCC is allocating those dollars to its properties. This year, Darkwoods was its signature property so NCC’s portion of that allocation went towards Darkwoods. And an ecological gift program from the federal government was also used, so the previous owner donated a significant portion of its appraised value as a “gift” to Canadians. That provides many opportunities for people with land they want to see conserved.

TCC a very fascinating organization because it’s a matrix-type organization. It’s national in scale but driven by local knowledge and local information, while being science-based. So, rather than splitting properties into little ranchettes or such, landowners can use these programs to protect their property in perpetuity and conserve their water and land resources. From that perspective, it’s a very easy system to embrace. The NCC staff makes it easy for contractors with the same values to apply their productivity, connections and communities to work with the staff. That way they can realize opportunities today and in the future.

NWNL Has your experience with Darkwoods further inspired your art?

PAT FIELD Yes. I put my art tools away for 6 months while taking on this part-time job…, which became a 7-day-a-week job. I took a dramatic cut in income because it was the right time, right place, right people and right organization. I had a sense of place. I had an opportunity to learn from the people managing the property now and for the next 5 years.

From a learning perspective, I got in on the ground level. Like most artwork, it became spontaneous only after a bunch of stuff has sunk in. Now that I am attached to the property with a sense of ownership, I’m sure my artwork will reflect that connectedness to the land. I’m just starting to learn the vastness of this property. It has over 500 kilometers of roads, but they are not like a highway.

While I’ve probably spent 20 days in the field, I haven’t seen all the roads. I haven’t seen forty of the fifty lakes. I haven’t been on all the water sheds. I’m getting a sense on the ground about how vast this property is and how different . . . My limited knowledge is like going on one trip to Africa and coming home espousing what Africa is. Going on the property for one day it’s impossible to espouse what Darkwoods. You need to spend years there to understand its complexity and values, and then synthesize them into a simple plan to conserve everything.

Many humans just say, “Well I’ll draw a line on a map, we’ll do this, and that’s what will happen.” But maybe art will help provide the motivation. I’d like to see artists come together on the Darkwoods property and be inspired by species like mountain caribou, a tree, a stream, the cool mist of the mountains or the snowpack.

I put my tools for sculpture away for the last six months, but I’m sure that when I return to my studio, I will be influenced by being part of this project.

NWNL What did you feel when first seeing mountain caribou in the wild?

PAT FIELD At the end of the third day I was on this job (March 1, 2008), I got a ride back from a Darkwoods Forestry Manager. As we drove up the summit, there were 43 of the property’s 46 mountain caribou, just 20 feet away! These animals had come out to lick off the salt onto the highway. After talking about them for years, seeing that group invoked a sense of wonder that I couldn’t talk about for a while because I couldn’t explain it.

I’d read for years that these animals travel in very small groups of 5 or 6, maybe up to 12. I knew they have an anti-predator avoidance thing, but here were 43 all in one place together. I was quite privileged to have that rare experience. At the same time, it brought up questions: “Why are they all together like that? Why has their behavior seemed to have changed?” Maybe we just don’t know enough about them. Maybe something has changed that they are all together now. So fascinating to be able to ask the caribou biologists, “Why did we see them like that?” It was striking to see a big, bull caribou with his antlers still on, cows wandering around, and the calves there all together as part of the landscape. It was a privilege to see it.

NWNL What are the tribes’ attitudes towards caribou, traditionally and currently?

PAT FIELD First Nations have had a long-standing relationship with mountain caribou since the beginning of humans being in this territory. They used caribou for meat, shelter, spiritual purposes – basically everything. That has obviously changed because these animals aren’t here anymore. They need to be recovered and part of that will include discussions and collaborations with our First Nation colleagues on how to create a political will to bring them back. That will be a very challenging discussion because, while their value sets are to take care of caribou, we don’t just want to rush in and say, “We’re going to transplant other animals or kill predators in order to protect them.” We need a longer dialogue to make sure that the habitat protection remains long term, so we’re not just tinkering with the animals. We have to control human behavior on the property so we don’t displace animals into sub-optimal habitats to avoid being eaten by predators or being pushed off cliffs, or being harassed by human activities. We must guarantee the opportunity for First Nations to be involved economically and to have some pre-connection with the animals and work with them. This generation of First Nations has lost that connection because those animals are so endangered and elusive. Most of us, including me, just don’t have enough experience to speak about such solutions – other than to say, “We must sit down and talk together.” Otherwise, it won’t work.

Posted by NWNL on April 19, 2024.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.