Saving Kenya’s Mau Forest

Mara River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Mara River Basin

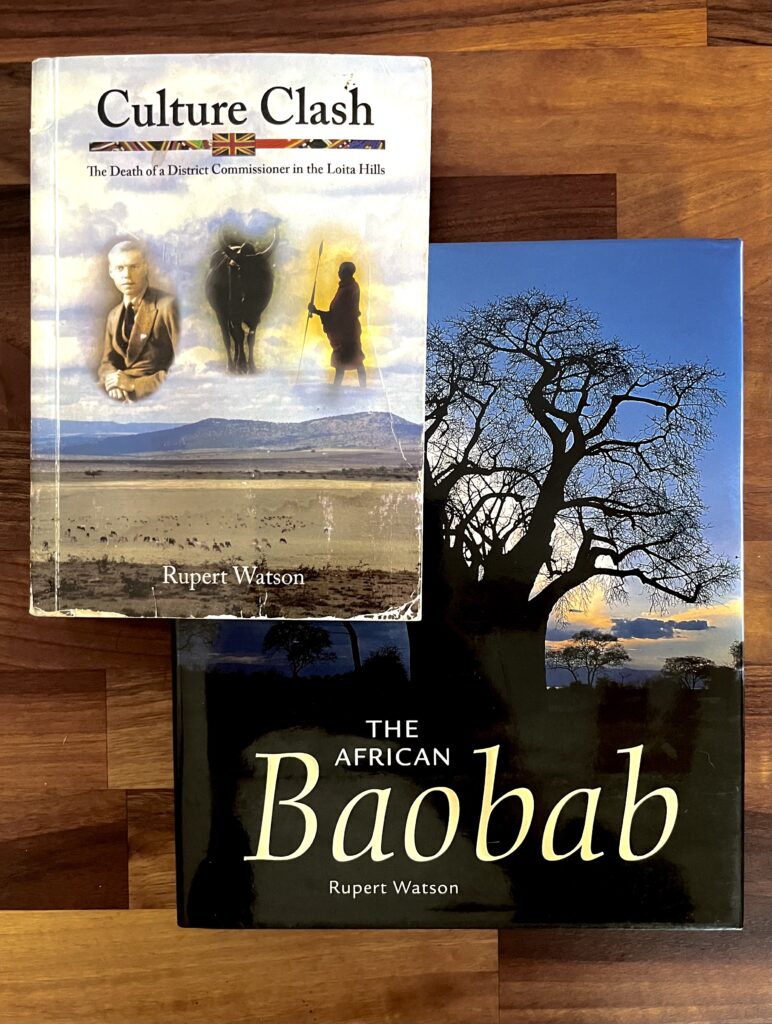

Rupert Watson

Lawyer, Conservationist, Author, Fisherman, Birder

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director and Photographer

Rupert Watson, raised in the UK, has lived in Kenya for 45+ years as a lawyer, mediator, author and advisor. As well, he has fished many of the world’s great streams. NWNL Director Alison Jones first met him during the launch of Kenya’s innovative Mara Conservancy when he offered legal advice on charters and other critical issues. Chair of the East African Natural History Society, Rupert has authored books on birds, trees and Maasai stories. And fortunately, NWNL is an appreciative beneficiary of his support.

WATERSHED CONFLICT v COOPERATION

LOCAL WATER MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS

GLOBAL DIFFERENCES re: CLIMATE & WATER

MAU FOREST – THE MARA RIVER SOURCE

FOREST TOURISM IN THE MAU?

MAU REFORESTATION

FOREST EDUCATION & PROTECTION

UNEP SUPPORT for MAU FOREST

WATER MANAGEMENT – LOCALLY & LEGALLY

MARA RIVER into LAKE VICTORIA

Water is much more a source of cooperation than a source of conflict. -- Rupert Watson

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

NWNL Hello Rupert. How nice to be able to walk down a dirt road, past a few giraffes, for this interview in your garden full of birds! Let’s start with the basic concepts you hold on various countries’ issues surrounding water quality, availability and usage.

RUPERT WATSON My message is a bit of a cliché that addresses an even bigger cliché – that water is a massive source of conflict and the next World War will be about water. and that. I think water is much more a source of cooperation than a source of conflict. What’s quite incredible, historically, is the many conflicts that have not happened. The last “water war” between states or nations was several thousands of years ago, about 1500 BC.

I see water as a source of cooperation. An incredible amount of cooperation exists. My message is that water is not a source of conflict. Yes, locally, it can be very much a source of conflict. But water is so crucial to everybody that we tend to get together to resolve issues, and wedo so quite successfully.

NWNL How best can we support that cooperation, both internationally and locally?

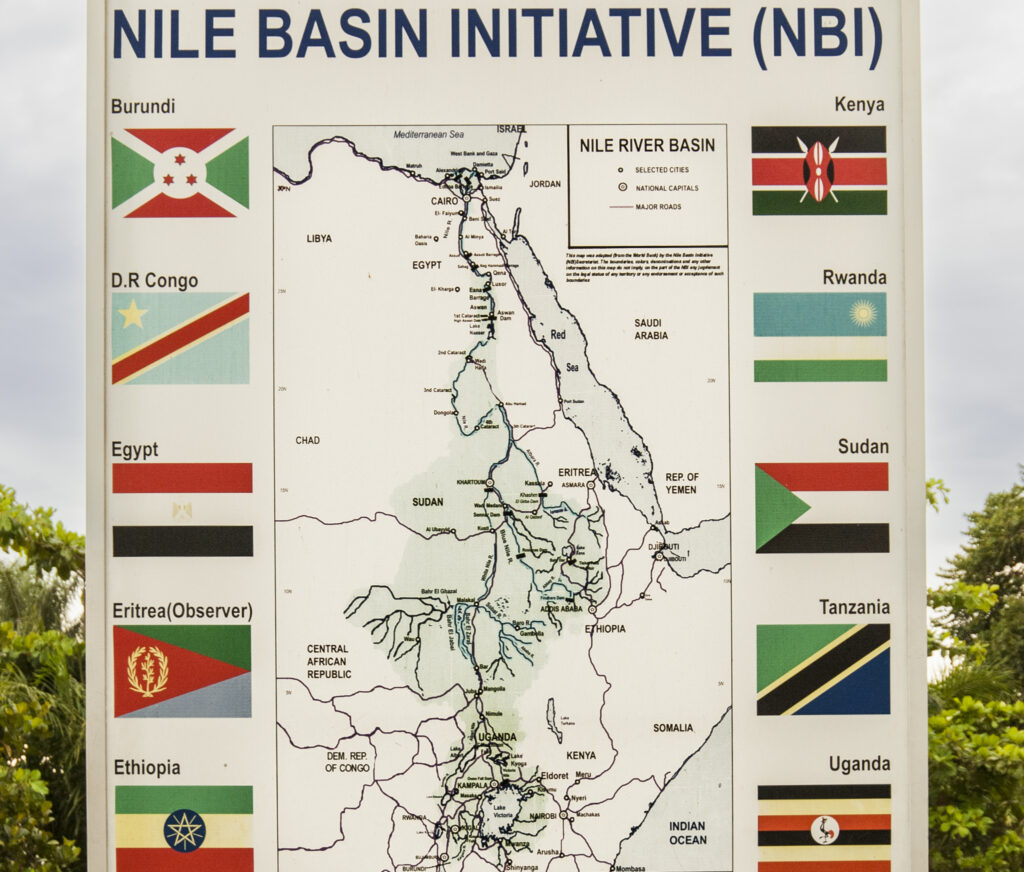

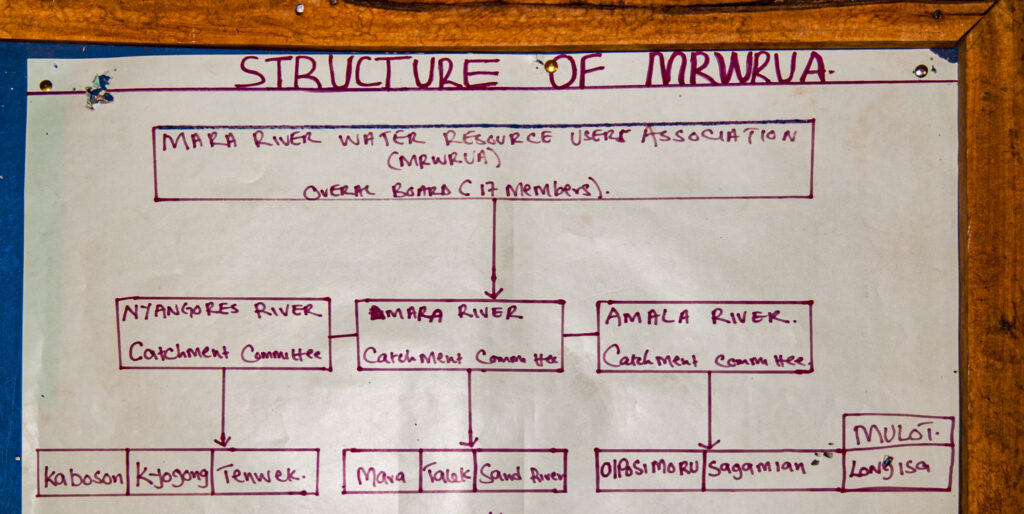

RUPERT WATSON I think the best approach is to create strong forums at a local level, such as our local WRUAs/Water Resource Users Associations. Another example at a bigger level exists in the multinational Nile Basin Initiative. Its 10 member countries* have formalized a Cooperative Framework Agreement allowing people to gather to discuss transboundary and local problems. *Burundi, DR Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda.

I realize we already have so many committees and institutions, gatherings, meetings, forums, workshops and this, that and another. But people need a place where they can say, “I have a problem. The water isn’t getting down to my grazing land.” Without community forums, a farmer could say “We haven’t got any water here, so we are going to move up into the neighbor’s area. Then, we going to push wildlife and our cattle onto others’ private property and ranches; and then up into more industrial areas.” Then, conflict is sure to ensue. Creating an available forum for resolution is critical, be it at a very local level or the Nile Basin level.

NWNL As you follow global water issues, what differences, similarities and interconnectedness do you see in N. American versus African water issues? Probably the most interesting aspect of NWNL documentation is in comparing these two continents we’ve chosen as our NWNL areas of study.

RUPERT WATSON Well, North America hasn’t yet had a water crisis. [NWNL Ed: One could argue the U.S. 1930’s Dustbowl was a water crisis.] Until a crisis happens on its doorstep, I don’t think the U.S. will seriously wake up to the importance of water. Recently, San Francisco has been short of water, and I know that the Colorado River Basin is dry. The Rio Grande is dry before it reaches the sea, but that is not a U.S. crisis.

A U.S. crisis would be Las Vegas residents waking up to no water and fearing their city could die. That serious type of crisis would wake up Americans. But Americans don’t wake up in Sana, the capital city of Yemen. Sana is now the most likely country capital on the planet needing to relocate because of lack of water.

That’s not a problem for Americans; and America is where all the big decisions are made. I think that until America has a real crisis, since it can’t realize that water availability elsewhere in the world is a real challenge. So, I’m itching for that crisis to happen in the U.S. If we ask people from NY in Kenya on safari to pee in the garden, they think you’re quite loopy. Water scarcity has never occurred to them. “Water is a problem?”

So threatened water supplies need to happen on America’s doorstep. That doesn’t exactly focused on your question of how to solve issues of water availability, but in some ways it does.

RUPERT WATSON What will happen locally? Will Nairobi have to relocate in 100 years? All its water tables are going down, down, down…. Everybody’s digging more bore holes [water wells], because it’s better to have a bore hole than a tanker truck deliver water. There comes a time when you can’t pull water up, no matter how deep your well is.

NWNL Is rain-harvesting a solution? It’s now popular in parts of Africa; and parts of the U.S. is beginning to consider it – especially Texas. Headlines now say some of its smaller towns are dry.

RUPERT WATSON But headlines won’t change Americans water awareness. Rain harvesting addresses using water that falls on your roof. Harvesting water off your roof to use domestically is inevitably a good idea, although some of that runoff would have gone into the aquifer eventually.

Nairobi has some archaic rules that ban rainwater harvesting, because they thought storage tanks became mosquito breeding grounds. Nairobi is not yet insisting new buildings have rain harvesting gutters and tanks; but it is a good idea, as is collecting water in shallow dams* to replenish the aquifer. [* a Kenyan term for ‘reservoirs’]

You might say water is never wasted because it goes down to the sea. It is then recycled up into the water cycle and comes back down again as rain. But, coming back to the Rio Grande and the Colorado River, all their water is taken out. People tend to forget about leaving something for the river. There’s a formula to always leave 20%, 30% or 40% of the water in the river so it can remain as a living ecosystem.

But the Colorado River residents’ judgment seems to have been, “Oh, well, all this water’s here for human consumption, so it doesn’t matter if there’s none left by the time the river gets to its estuary. That’s just how it is.” But leaving only a trickle in the estuary” is not how it should be.

NWNL There are facts supporting the differences in daily average water consumption between Kenya versus Europe and America. As an American, I find it embarrassing, especially as towns in Californians are rationing their water supplies. For instance, homes in East Porterville CA receive 50 gallons/day pumped from a truck. Many of those residents drive to the local high school for their showers.

NWNL Do you see water availability and use changes due to climate change?

RUPERT WATSON I think climate change may be responsible for this, that and the other. Perhaps the climate is changing, although I question whether we’ve been around long enough for a pattern to emerge. The developing world says:

None of this is our fault because we’re not really polluters. However dirty Nairobi may be, it isn’t really a polluter on a bigger scale. The developing world suffers from things happening in the developed world. So, someone should compensate us for all of that.

As I’ve said, the developed world hasn’t yet had some huge crisis directly attributable to climate change. When that happens, people will wake up. Today, it’s still too remote. Many Kenyans don’t understand that what’s being done in the developing world causes them harm for which they’re not responsible. Yet, I think there’s much overuse of blame that climate change is responsible for the developing world’s problems.

NWNL How can North America and Europe work together with Africa on freshwater issues? Should North America and Europe help fund a continent lacking finances to build water infrastructure, such as dams and boreholes? Should they be educating Kenyan watershed stewards? How can the cooperation you talk about be achieved?

RUPERT WATSON Funds for the Nile Basin Commission is money well spent because that is where dispute prevention occurs. The West could best help Africa’s water problems by supporting and encouraging more trans-boundary cooperation.

At Kenya’s local level, we have Water Resource User Associations [hereafter, WRUAs], whereby all within a particular basin get together and hopefully appreciate each other’s problems. WRUAs serve to prevent disputes. Increasing supply often happens somebody comes along and says, “Oh, these people need a borehole.” Indeed, people should have the right to more water. But producing more water very often produces more damage and conflict. Encouraging many more people into the area, doesn’t support local water needs.

Much of West Africa has buckets of water, but I’m sure the Niger River Basin has many of the same problems as those facing the Nile River Basin. Their lack of flow is not yet quite as challenging that facing the Nile River Basin where there are potentially horrific political ramifications due to 97% (I think) of Egypt’s water coming from the Nile.

Overall, I encourage finding ways and means to encourage cooperation, rather than short-term solutions that put “fingers in the dyke” to address problems here and there. It would be good to get “big thinking” into Nairobi City Council meetings to get more forward-thinking solutions to Kenya’s future water-supply needs.

NWNL Thinking 30 years hence, what will be the demand for water here?

RUPERT WATSON If Nairobi and the prosperity of average Kenyans keeps growing like this, what will be the demand for water in 40, 30, 20, or 10 years? Do we have the supply for those needs? If not, let’s start thinking about that problem – now. Rather than short-term solutions, I think it is more important to help the thought process and only then help implement some of the conclusions from that thinking.

NWNL Can North Americans learn from Africans who’ve already faced major droughts and prolonged water shortage? It seems Kenyans learned to be careful long ago.

I recall that each North American uses 100+ gallons/day, while 5 or 10 Kenyans sharing that one-person amount.

RUPERT WATSON I don’t see how the experiences of Africa might teach America. We could say, “Come here to see a real drought!” But most people don’t die directly from lack of water. The UN’s World Food Program is brilliant at providing food for starving people; and somehow there always seems to be enough water. Cattle may die from a combination of lack of food and water, and somehow people slowly move away from dry areas.

So, we don’t really hear about a serious, immediate problem or a particular area struggling long term because it’s run out of water. I don’t think Africa is teaching America much right now.

NWNL I was thinking about recycling and saving buckets of water and other simple practices…. Regarding the lack of water causing peoples’ deaths, I read that many deadly health issues are caused by dirty water – not just a lack of water.

RUPERT WATSON Yes, especially in the slums. And I sit here complaining of a water shortage, when there are families in slums not far from here that live off one bucket a day. There, after washing the dishes, that water is used elsewhere, and then that goes elsewhere…. But I doubt that kind of reuse of water will resonate with the average American.

NWNL There are many constraints in the availability of water in Africa versus America. In the U.S. pipes and infrastructure distribute water. But Kenya has fewer of those means for delivering clean water ,which creates challenging sanitation issues.

RUPERT WATSON The disease issue, yes. People die from a lack of clean water here, absolutely. We face problems of water quantity, and water quality. That’s something to which I’ve not paid enough attention. I tend to focus more on quantity than quality.

You’re right. Many people here die due to dirty water. I think there’s much the developed world can teach Africa about improving water quality. I can imagine research here on improving water quality could be useful elsewhere, especially in removing various diseases from the water. Probably most of that research occurs here rather than in the developing world where water is clean to start with and people know how to clean it.

NWNL One sad statistic says that 217 children will die in this one hour we are now sharing to discuss water issues due to poor sanitation and water-related diseases.

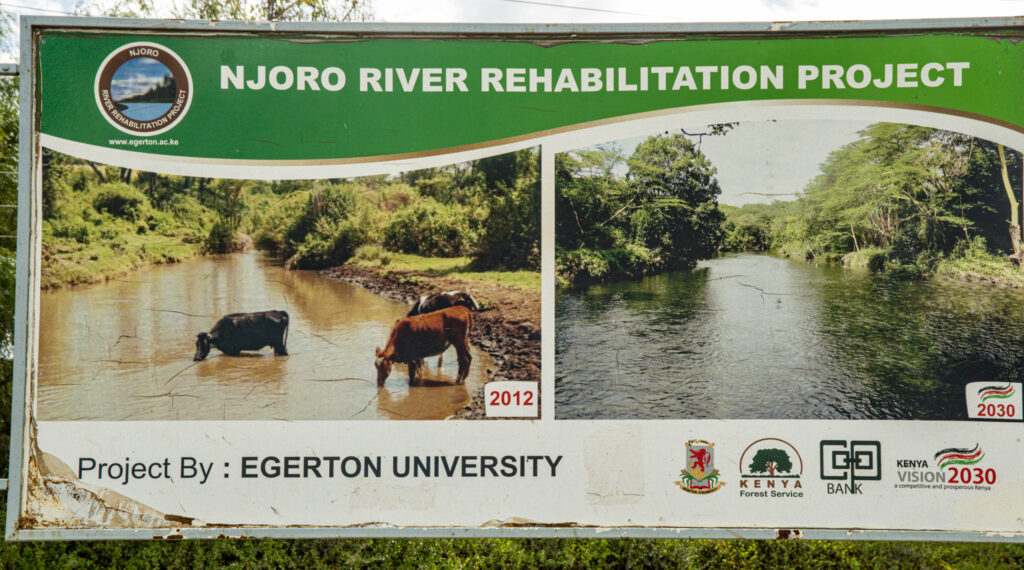

NWNL I just re-visited the Mau Forest, where approximately 25% of forest has been lost. In 2009, when I first documented it, I had great hope that Kenya would address the deforestation in the Mau. I talked to folks at UNEP. I met and interviewed many people in the Mau – from Indigenous Ogiek teachers, old people in IDPs, stewardship groups to local elementary teachers explaining the importance of trees. But I must say, three years later, I’m quite discouraged. I haven’t seen much improvement. Instead, I saw more problems.

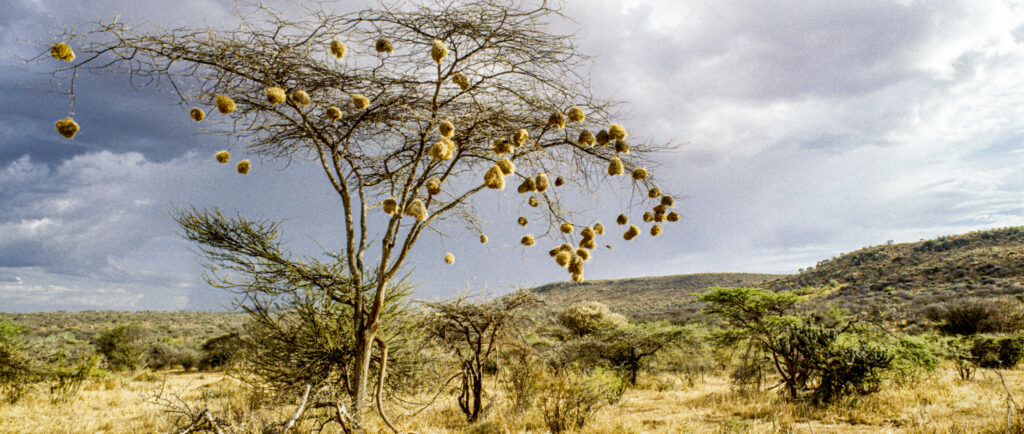

If the trees are all cut, many will be affected. There’ll be no rainwater retention to supply downstream supplies during dry periods; no habitats to support Kenya’s wide range of forest and plains species; and thus no wildlife tourism downstream. The values of this forest flow with the Mara River, through Kenya’s Maasai Mara National Reserve, Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park, and finally into Lake Victoria.

The Mau Forest is the largest headwaters (also called “water tower”) in Kenya. Does it have a dollar value, or a value measured in Kenya shillings? What is your own assessment?

RUPERT WATSON First of all, I think perhaps the value of the Mau Forest is as a great sponge. If we destroy all forest cover, then even if same amount of water does or doesn’t fall on the area, won’t be retained in the same way. If we don’t collect it lower down, which we don’t now, we’ll get a huge flood. Even if we had dams lower down, the dams would fill and new rainwater would overflow and disappear.

But with good forest cover, as we have Mount Kenya and Aberdares water towers – it’s incredible how slowly the water leaches out like, just as with a sponge. Even in droughts, those streams will still flow.

The average Kenyan can make the connection between keeping the forest and a continuous flow in our streams. They’ve seen and learned that when you lose forests on the top, you lose the continuous flow in rivers below.

Furthermore, as a conservationist, I’d love to see a healthy Mau Forest. I think there are still some rare and endangered Mountain bongo up there. I’d love to see the Mau become another park or a reserve for animal habitat, tourism and human residents – at least around on the outskirts. But its main use always should be as a water tower — a sort of invisible, natural reservoir.

NWNL Do you know of any monetary figures assigned to its value?

RUPERT WATSON No, and I doubt I’d believe them if I did hear them. They’d likely be $1 billion, $2 billion, $3 billion. or…. Everybody rams up numbers to the nearest billion, showing that they haven’t a clue.

But, forgetting its exact fiscal value, the momentum to save the Mau seems to have been lost, as you say. We’re now coming up to an election, so politicians tend not to be unpopular by hammering on about the Mau and how people there need to be resettled. So, the Mau topic is now not discussed at all.

And where would those people go? Sadly, there are still so many IDPs [Internment Camps for Displaced People] left over from our last election’s problems. It doesn’t seem to me there’s very much fair land left in Kenya. So where can IDPs and people from the Mau go?

NWNL If people are forced out of the forest, should the government find land for them – land you say doesn’t exist? I’ve heard rumors of an instant settlement because the election’s nearing. It seems the government now wants to get rid of the eyesore of IDPs and this problem that concerns everybody. But before commenting, please explain the expression “IDP.”

RUPERT WATSON I use “IDP” [initials for “internally displaced person”] to describe an internal refugee. After our problematic last election due to tribal violence, we had many IDPs. People ended up in tents since their farms were being occupied by others.

Often people were moved to areas where they didn’t feel safe. Basically, if A kicks B out of B’s land, then that is a crime. The government may be responsible to enforce the law and help them get their land back. But it doesn’t have a legal responsibility to provide new land for them.

It’s easy to say to land grabbers, “You can’t have this land. We’re taking it back.” But if a parcel has gone through a chain of buyers and sellers, it’s very difficult to say, “You shouldn’t be here, but we’ll give you a new piece of land.” I’m not sure that’s the government’s legal responsibility. But there’s a strong moral responsibility. Also, the world is watching.

NWNL But weren’t many now in the Mau Forest, given land either by politicians either in this or a former government to get votes? They didn’t just grab it – they were given it. Some are just squatters – but some were given the land and then removed.

RUPERT WATSON Then they must be compensated. If they had a good title deed and the land came from the government – whether bought or given – it’s theirs. If given, and then the government says, “Well, now we don’t want you there;” there should be compensation.

With our shortage of land, where do we put people? Some say the government could buy a ranch in Laikipia for evictees, but ranchland doesn’t lend itself to small-scale farming.

NWNL There is also a loss of habitat for species when you lose a forest….

RUPERT WATSON Yes, it would be great for conservation to restore space for creatures. But given this country’s rising population, there’s less and less room for wildlife. The people need more space, and that comes at a price, including the loss of land previously in conservation, officially or unofficially. And the division of pastoral land turns into residential, agricultural plots.

NWNL If the forest was preserved, bongo and other species would likely multiply. Could the Mau then be used for tourism, as well as a pristine water catchment area? Then people could pay for the chance to appreciate this ecosystem and its forest species. Could that help support the forest and the large Kenyan population that needs support?

RUPERT WATSON Would tourism justify the retention of the forest? It’s a real sadness to me that justifying conservation nearly always boils down to ”If you keep this, tourists will come, and you will benefit from their dollars.” Most often the promise is not realized.

Very seldom do we have conservation for conservation’s sake. I think it’s not in most cultures’ ethics. I do think it is in the Maasai ethic to some extent – and in the Samburu ethic to some extent. But it’s not in most ethics to keep a forest just because other creatures have a right to life as well us. We all should be preserving biodiversity. It’s rarely a viable argument We feel we must dress up conservation in, “Let’s make it a tourist preserve.”

That’s perhaps the only argument you can give, and it’s probably worth a try. Yes, Kenya’s tourism is doing very well, and people always look for new destinations. As well, the Mau Forest is not too far off the beaten track from the popular Maasai Mara or Lake Nakuru destinations. So quite possibly that could work, and the reality could match up to the promise.

NWNL For that you must build fencing, which Colin Church has been doing in part of the Mau – and did in the Aberdares.

RUPERT WATSON Fencing works. But, I always think fences are an admission of defeat: “We’ve tried everything else, and now we’re stuck. We’re going to fence.” But I think some of those fences are really working. If you have the Mau’s two-way problem of not wanting people going into the forest for varied reasons, and not wanting the animals coming out of the forest, then fencing is a real seller. But without animals coming out of the forest, it’s not such an easy sell. We’ve all seen fenced forest land. People don’t like being fenced out, “It’s stopping us getting into the forest, and we need to get into the forest for cultural, economic and all sorts of reasons.” And the fence won’t stop animals coming out, because there aren’t any animals left to come out.

Maybe Colin can argue that even if it’s a one-way problem – just keeping people out – it still works. I hope he can.

NWNL Well, elephants would need to be kept out because they’d destroy the “shambas,” the local little farms.

RUPERT WATSON But I question whether the Mau Forest has elephants; and without elephants, whether the Mau is a two-way problem.

NWNL I didn’t think any elephants remained in the Mau Forest either and I would have agreed until this week. I just read three elephants have been poached in the Mau Forest.

RUPERT WATSON Really? That’s wonderful to hear that there still are.

NWNL Well, maybe those were the last three.

RUPERT WATSON I wonder if they came in from outside or if they’ve always been in there?

NWNL Perhaps Kenya could restore elephant in the Mau, and make it a protected reserve with bongo and other forest species? There are bongo up in the Mau’s Eburu section now. They definitively know that there are two little groups.

RUPERT WATSON But I don’t count Eburu as part of the Mau—

NWNL Apparently, Colin’s going to fence that first apparently, and then expand fencing from there. While hearsay, I hear that apparently Colin wants to finish fencing Mount Kenya and start fencing Eburu in a month. He has funding. He’d then expand it…. The Aberdares took 20 years to fence, so we know Colin does look far ahead. It seems to me that fencing really is the only answer, even though I didn’t think so four years ago.

NWNL Do you have any thoughts on the success of the Mau Forest Reforestation Secretariat’s current efforts?

RUPERT WATSON I don’t know enough about them. But the worst case of forest not coming back that I’ve seen is in Madagascar, where there’s a lot of exotic creeper from overseas. By “exotic,” I mean “not local to that country.”

But regarding the Mau Forest – even if you clear cut areas – you can manage regeneration. Even without planting, there’ll be a fantastic number of seedlings and things still in the ground. Obviously planting will help. There are people who know what you need to replant in a particular instance, or what you shouldn’t replant. They know that one type of tree will regenerate, but another never will. They know if we must help this species or that to recreate the old mosaic and what was there.

NWNL Does it matter, as far as the water retention of a forest, whether a deforested region comes back with its original indigenous trees or with a new tree species?

RUPERT WATSON I imagine reforesting exclusively with eucalyptus would take more water out of the soil. I don’t know enough about new trees making their own rain. There’s a lot of uncertainty about that. But I think you could reforest and still retain the original benefits of the ecosystem of the water catchment.

NWNL So you don’t need the original indigenous trees, or those lovely indigenous cedars back, to serve the role of retaining water?

RUPERT WATSON To me, the important thing is forest cover. I’m generally very pro-eucalyptus, so I think if you covered a whole swath of the Mau Forest in eucalyptus, then it may not be as effective at water catching as previous trees there were, but you would have a fantastic stand of timber.

NWNL You stated that the average Kenyan now understands the connection between the forest and downstream water supplies. How did that happen?

RUPERT WATSON I think two things happened. When you ask if Kenyans now better appreciate the connection between retaining forests and water supply, I’d say, “Yes.” Education has been much better through the press, the schools, and at all sorts of levels. But also, people have seen with their own eyes that, “Hey, this stream used to flow all year ‘round; but it doesn’t now!” People are old enough to remember that the stream used to flow, but it doesn’t flow any longer.

They ask why. Much of the Aberdares is protected, so it’s not an issue there. But unfortunately, there are many streams that now have lower flows. People asked why. The answer has come out that its because water is being taken from up above since we destroyed all our trees. People are told to look how rainwater all flows down in two days, and then it’s gone. I think experience and education have both combined to bring the reality home to roost.

NWNL One of the happiest experiences on my Mau trip this year was randomly walking into a school where they were planting trees. We went in and saw students’ open notebooks full of drawings of trees and rivers and a mountain. Serendipitously, that’s what they were studying that day. So, I can agree with you that this message has gotten into school curriculum.

NWNL And the message is repeated in the press in an adult manner. It seems there are three learning tools –experience, teachers and news.

Do you think the Kenya government really cares about the Mau Forest, or is it just trying to impress the rest of the world that it’s doing something? How deep is its motivation? Will it take another huge drought for them to really be re-motivated?

RUPERT WATSON I don’t think they really care about it. Particularly now, the government has many individuals concerned about their own private motives and agendas. They’re not really interested in the bigger picture. The Mau Forest is perceived as just a local problem for the Ogiek people and others living around it.

I doubt the Minister of Tourism will say, “Hey, the Mara River comes off the Mau Forest – one of the Seven Natural Wonders of the World with the migration crossing over the Mara River! So we have to look after its forest.” Maybe after the election that will happen.

NWNL That puts an interesting political perspective on it.

NWNL In 2009, when we first filmed this fantastic watershed. Travelling from the Mau Forest to Lake Victoria, I heard many cries for restoration of the forest. But now it seems to me that that concern is now gone. I’ve wondered if their attention gone to something else bigger, or was their concern not very strongly felt? Now I understand the upcoming elections have diverted your politicians from these concerns. Fortunately, UNEP is now playing a role in helping reforest the Mau now. Are you connected with that effort?

RUPERT WATSON I’m not.

NWNL I’ve twice interviewed Christian Lambrechts, while working for UNEP as the former Policy and Program Officer and working in the office of Kenya’s Vice-President. He encouraged and supported governmental attempts to restore the Mau Forest. He’s now Executive Director of Rhino Ark Charitable Trust.

RUPERT WATSON Yes, Christian Lambrechts is an unusual person because he takes a big interest in what’s happening locally. I’ve been involved with him occasionally, but I don’t know if he personifies the UNEP mandate. Given the fact that he’s interested in the Mau indicates that UNEP is really committed up there.

We all have wished that UNEP would take more interest in Kenya, since we are its host country. Yet, it may be difficult, because of internal politics and so on. I understand UNEP can’t favor one country or another, but it would be nice if UNEP holds onto this project.

NWNL Recently, the mandate for the UNEP Secretariat to continue UNEP’s Mau Forest Project was extended until spring, 2013.

RUPERT WATSON Oh, good. You’ve seen more than I have because you’ve visited the Mau. Perhaps you saw UNEP vans running around or UNEP banners and posters in tree nurseries.

NWNL Yes, and I saw many flags when at the Nairobi UNEP World Headquarters for an environmental meeting in 2012! I agree there should be some way Kenya should benefit from that headquarters set up across town from here.

NWNL Rupert, what other topics might you want to address this afternoon?

RUPERT WATSON My focus is on being effective. If it’s not a two-way problem, it won’t be particularly effective. Of course, there is an effect, even if a fence doesn’t stay. Even if you’re left with just posts, they have the effect of saying, “This is the boundary.” A partial fence says something, — even if it won’t keep people out. Even if there isn’t a two-way problem, it does demarcate.

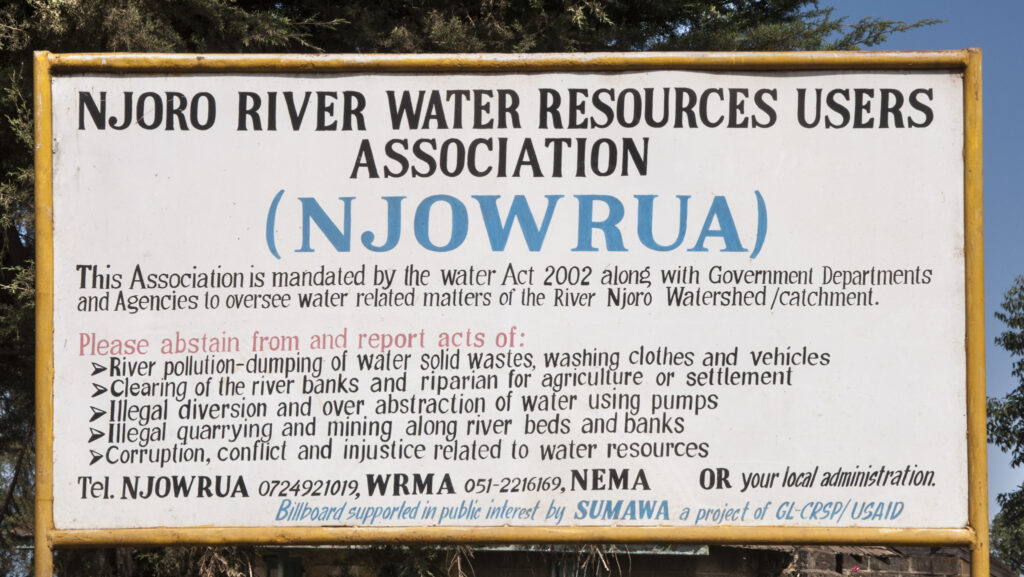

NWNL We earlier touched on Kenya’s Water River Users’ Associations [WRUAs]. What’s the effectiveness of their river regulations? At the eastern edge of the Mau Forest, many go to the Njoro River to do their wash, despite nearby WRUA sign regarding rules, such as:

You have to build your homes at least 100 feet from riverbanks.

Stop dumping waste in the river and employ no tilling practices….

NWNL What have WRUAs accomplished, what changes they have affected, and how widely accepted are they?

RUPERT WATSON The WRUAs were formed under the New Water Act—no longer new; but rather, several years old. They are part of the government’s new policy to devolve management of natural resources to the users thereof. You used to get water permits and such from water headquarters in Nairobi since everything was done centrally. Now management has been devolved to the users; and the same goes to the forests. We also have Forest Users’ Associations, as well as Water Users’ Associations, with the idea to get all the people in the same basin together to give them a say in the management of that river basin.

Kenya is divided into 8 WRUAs, I think, in accordance with its8 basins. The one in Nanyuki [on the Equator] stretches out to Moyale on the Kenyan/Ethiopian border. Dividing a country into basins is a very good idea; and gives the WRUA’s the remit to assemble users of a particular basin, usually on a very local level, to give them a share in management and a share of the problems. This gets them talking and gets them together.

The Njoro sign listing local rules you mentioned illustrates what WRUA’s are doing. Many of those rules have been here since colonial times. The fact those rules are publicized is fantastic. It means the WRUAs are bringing peer pressure to bear. That counts for a lot in those tightknit communities. Now, enforcement is another thing.

NWNL Is the institutionalized structure of Kenya’s 8 river basins, with WRUAs in each basin, as effective as it sounds? Could that approach be transported as an effective solution for other countries? I’m not sure we have anything as effective as that in the United States.

RUPERT WATSON While I often use it as an example of local cooperation, I don’t know to what extent it happens elsewhere. Maybe America and other places with looming water shortages could adopt that idea. There’s a lot to be said for it, whether for the Nile River or the Njoro River.

NWNL When I documented the Mara Basin in 2009, I heard about WRUAs – and had a hard time getting that mouthful out—I still do! Yet I was very impressed. I wondered how well they worked. Then. this year I saw that sign on the Njoro River. It reminded me of so many other similar signs I’ve seen here. So yes, cooperation works here, at least!

NWNL Have you seen WRUAs work in other areas in Kenya, or elsewhere?

RUPERT WATSON Yes – particularly around Mount Kenya. There’s a lot of big business there and big farmers with infrastructure that can help people set up an association. They can get a lawyer in Nairobi to help form the association. That’s a big hurdle to jump through. It must be under the Kenya’s Society’s Act, not the Water Act – thus it takes money, contacts and all sorts of things. So, powerful WRUAs are often where there’s a big business that can stimulate formation of a WRUA and provide a meeting place, plus transport so people from different areas of the river can gather to study their problems.

Basically, getting people together and money to form the association is not easy. You get a kickstart if you have an existing business or wealthy people committed to clean water – even if for selfish motives. No interest like self-interest! There are some fantastically successful WRUAs, and credit is due to those WRUAs without a kickstart, but merely supported by local people getting together.

Local people in the Mau Forest wonder, “What should we do with this river?” Then they ask, “How can we form Associations? How will we find the necessary connections in Nairobi?” They need to employ a lawyer and to find money for this, that, and the other. It’s very difficult.

NWNL Does Kenya’s new Constitution give county governors more power to protect the Mau Forest?

RUPERT WATSON I’ve not studied the new Constitution, nor the way it will be implemented. But remember, it’s one thing having it in writing, and another to have it implemented. I don’t know how the new Constitution affects water in Kenya.

NWNL I’ve talked to people who have faith in the new version and are excited about it – but nobody seems to know what it says, only that it grants new powers to the governors and new counties. I’ll come back to see in a year or two.

RUPERT WATSON I don’t know whether we’ll know any more by then.

NWNL We’ve talked about the impact of the Mara River on wildlife, biodiversity and tourism. Do you have any thoughts on how this river effects its terminus, Lake Victoria?

RUPERT WATSON One might begin by saying Lake Victoria is the start of the Nile.

NWNL Ah, yes. Lake Victoria loops the Mara River into the Nile River – both rivers being NWNL case study watersheds. The two Lake Victoria/Mara River issues we’re investigating are impacts of Mara River effluents on the lake’s water quality and impacts of the Mara River’s volume on the lake’s water level.

RUPERT WATSON Well, I’m always amazed that Lake Victoria doesn’t go up and down more. Some time ago there was a lot of finger-pointing at Uganda for letting out water over the dam at Jinja, because it was having terrible electricity shortages. That issue continues, and soon it will be partially relieved by the new dam at Bujagali Falls, but only partially.

I think Lake Victoria is amazingly resilient. There are current issues, including the return of invasive water hyacinth. For that, they’ll have to bring back the beetles which did a fantastic job of biologically controlling the water hyacinth. As well, I gather harvests of its Nile perch are going down and down. Plus, the average size of fish is getting smaller and smaller.

But it is a resilient lake – perhaps notwithstanding, or perhaps because it’s shared by three riparian countries. I don’t visit it enough, but I do hear the fish yields are significantly down.

NWNL I too hear concerns over fish populations in Lake Victoria, and Lake Turkana. Fortunately, Lake Victoria has a resilience that’s unlike other Rift Valley lakes that don’t have the same checks and balances on the lake’s governance and controls.

RUPERT WATSON Yes. There is a somewhat cooperative management of Lake Victoria.

The East African Community has a Lake Victoria Basin Commission (LVBC). I’m not sure how effective it is. You might say that it is 3 countries all behaving selfishly – a recipe for disaster rather than a recipe for conservation. I don’t know, but I do find Lake Victoria very resilient, but I don’t really know enough about the cooperative management of the 3 countries.

NWNL That’s a good conclusion to my Mara River Basin questions. After a break, we’ll talk about the Omo River Basin, its Lake Turkana terminus and impacts from Ethiopia’s proposed hydro-dams. Thank you so much for your years of supporting the Mara River Basin as a lawyer, conservationist and a fisherman. Here’s to many more watershed management partnerships across Africa!

Also see Part 2 of this interview with Rupert: “African Dams & Energy”

Posted by NWNL on January 22, 2024.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.