Reconstructing Prairies

Mississippi River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Mississippi River Basin

Daryl Smith

Director of Tallgrass Prairie Center, University of Northern Iowa

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Executive Director

West to East: Shortgrass to Tallgrass Prairies

Prairies and Agriculture

To Till or Not to Till?

Prairies & Water

Ecological Services’ Monetary Values

Threats to Today’s Prairies

Watershed Approaches to Prairie Conservation

The Tallgrass Prairie Center

Creating Your Own Prairie

Creating Markets for Native Seeds

Invasive Species & Climate Change

Bison on the Prairie

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.

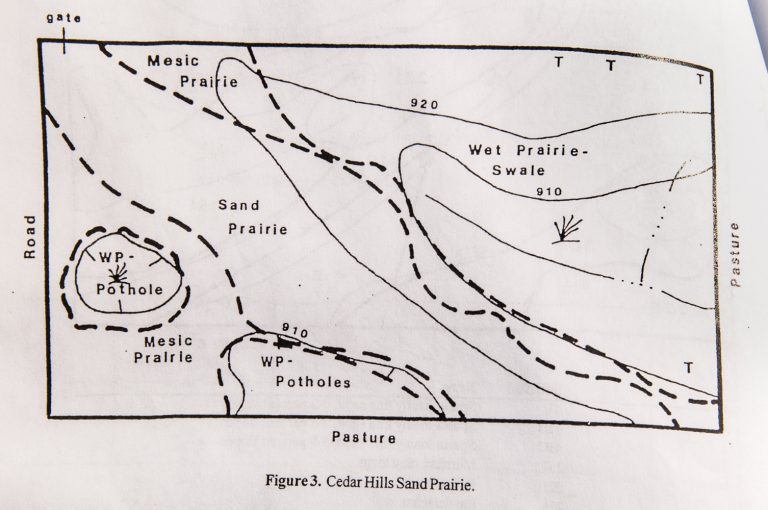

This was NWNL’s second interview discussing values, threats and stewardship of the Upper Midwest prairies – both held on the same day. Our “Row Crops on the Prairie” interview with Dr. Laura Jackson focused on regenerative farming, modeled on prairie vegetation and its ecosystem services. In this next meeting with Daryl Smith (prior to visiting his nearby Cedar Hills remnant sand prairie, our discussion focused on reconstruction and preservation of Iowa prairies and his Plant Iowa Native program sharing ways we each can help in restoring our valuable prairie system.

NWNL Hello Daryl. Let’s start with your background that brought to being the Director of the Tallgrass Prairie Center.

DARYL SMITH It’s a long story. I became interested in prairies after I arrived at the University of Northern Iowa. After doing research on plant physiology, I became interested in prairies due to a remnant prairie re-discovered a few miles from here. Then, during my graduate work at the University of South Dakota, I was diverted to plant physiology. I planted a prairie on campus in 1973. I’ve since became more deeply involved. Some people would say I’m “obsessed with prairies.” But gradually we coalesced all projects we were working on at the Univ. of Northern Iowa and across Iowa into what is now the Tallgrass Prairie Center.

NWNL What was the value and size of the Upper Midwest prairie before Europeans arrived?

DARYL SMITH I’ve focused more on tallgrass prairie than on the mixed-grass prairie farther west or the shortgrass prairie among the foothills of the Rockies. There were about 240 million acres of tallgrass prairie originally from northwest Indiana across Illinois, Iowa and into Kansas and Nebraska and the Dakotas. It extended north across Minnesota into a little bit of Manitoba, and then south as far as Texas and Oklahoma. There were some outliers to the east in Alabama, Mississippi, Ohio and Kentucky that were sort of a part of tallgrass prairie.

Early on, I became involved with prairie reconstruction, rather than prairie restoration. Prairie restoration starts with a degraded prairie with remnant vegetation and tries to enhance that vegetation and bring it back. But prairie reconstruction starts fresh with crop fields or where the prairie has been completely removed, and then brings in plant material or seeds to start the prairie.

Once you become involved with prairie reconstruction, you rapidly become involved with prairie preservation too, because no matter how good a prairie you reconstruct, it cannot equal the original prairie in terms of quality, diversity or other factors related to the prairie. So, in the last 40 years, I’ve been involved in reconstruction, restoration and preservation of prairies.

NWNL Can you explain the difference between the 3 different types of prairies?

DARYL SMITH Comparing the eastern tallgrass prairie with prairies further west, there is a gradation of tallgrass prairie vegetation here in the eastern part. Moving further west, the mid-continent prairies integrate into the mixed-grass prairie. Then the shortgrass prairie is still further west.

Basically, the height of prairie vegetation correlates to rainfall amounts. A you move from the Rocky Mountains further east; rainfall increases after what’s called “the rain shadow.” After Pacific Ocean moisture has crossed two mountain ranges, and lost water both times in crossing, on the east side of the Rockies drops about only 10 to 12 inches of rain per year.

As you continue moving eastward, rainfall increases because fronts moving up from the Gulf of Mexico bring moisture with them. Also, Canadian fronts come down and create rainfall and thunderstorms. So, as you reach western Iowa, there is about 28-30” of rain per year. In eastern Iowa, you get 33-35” of rainfall. Even further east, rainfall keeps increasing and forest vegetation develops. In one region to the east of the Tallgrass Prairie, there’s a mosaic of prairie and woodlands which we call a savannah or prairie-forest interface. There are also some outliers in Ohio, Indiana and further east.

NWNL Thank you for that differentiation of prairie systems. Back to northern Iowa’s tallgrass prairie within the Upper Mississippi River Basin, how does that coexist with agriculture?

DARYL SMITH Considering the value of Iowa today – in general and northern Iowa specifically – requires looking at the heritage or benefits of the tallgrass prairie, because it provided the rich black soil we’ve mined for top agricultural productivity. The value of the prairie is still present as we use it to farm row crops. That’s the particular value of existing prairie land.

But there also is sort of a negative value, because annual farming, cultivating, and tilling land is potential soil and wind erosion. In this part of the country soil erosion is more a threat than wind erosion. Our eroded soils enter various tributaries that flow into the Mississippi River and are then carried to the Gulf of Mexico, creating its “dead zone.”

NWNL Great point. Back to agriculture, could you please describe row cropping?

DARYL SMITH. Row cropping involves planting crops like corn or soybeans in rows and leaving some space between the plants. My father planted the rows much further apart than we do now. Improved technology has allowed us to reduce the amount of space required between those rows. In contrast, farming oats or wheat involves broadcasting seed, so you don’t see it in rows.

NWNL What are the different impacts of those two different farming methods on the environment?

DARYL SMITH Row crop seeds are planted with space for open soil, allowing rainwater to hit that soil and thus easily erode it. However, broadcasting seeds for crops such as oats or wheat spreads seeds widely, lessening the impact from raindrops hitting and disturbing the soil, allowing water to float away. Corn is designed or has evolved so it catches much of the water and funnels it down to the base of the corn plant; but there are areas where corn doesn’t intercept the rainfall. And so, its roots are not as widely spaced throughout the field, whereas broadcast crops tend to be much more widely spaced. You’ll likely not get as much erosion from a broadcast-seeded field as from a row-crop field.

NWNL What is your point of view on using cover crops for carbon sequestration?

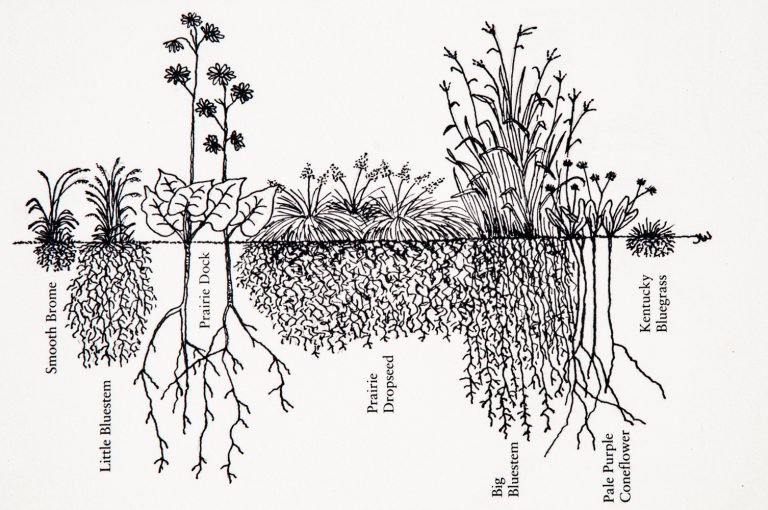

DARYL SMITH Looking at carbon sequestration, involves looking at the amount of root vegetation present. Most of our crops tend to be annual plants that lack extensive development root systems. Native prairie plants have very extensive root systems and are perennial vegetation. Prairie root systems stay in the soil since they are not cultivated or started anew again each year.

NWNL How much of the year are corn and soybean roots in the soil, in contrast to the perennial presence of prairie roots?

DARYL SMITH Typically, corn is planted in April and harvested in October, so those roots are in the soil about 7 months a year. If they don’t plow in the fall, dead roots stay there a while. Although not living, these roots provide some soil-holding capability. But perennial plants from the prairie are in ground year-round. In fact, 60 to 90% of the total biomass of prairie plants is below ground. Above-ground prairie vegetation is only about 10 – 30 or 40% of its in-ground extensive vegetation of root systems, whereas a much higher percentage of corn plants is above ground.

NWNL It seems one big problem with farming is in tilling the soil. How many farmers still practice “no-till” farming?

DARYL SMITH There’s been quite a bit of education about “no till” farming, and there are certainly a lot of benefits of “no till,” especially regarding the erosion caused by tilling the soil to a powder each year. One problem with no tilling is a greater use of chemicals to fight weeds than in tilled farming. There are other trade-offs as well; but in terms of soil erosion, no till is a benefit without a doubt.

NWNL What percentage of farming here is tilled?

DARYL SMITH You probably need an agronomist for that, but in general, almost 100% of our farming now is corn and soybeans, and sometimes we alternate 2 years of corn and 1 year soybean. It varies from farmer to farmer. But 50 or 60 years ago, when I was growing up on the farm, there was a lot more crop rotation. My father might plant corn one year and oats the next, while seeding alfalfa or clover into the oats so he could cut hay the third year.

We also used to rotate crops – maybe only producing corn 1 year out of 3, while also producing oats. And we did a little bit of farming with horses. (That reveals how old I am!) There was as much a need for oats, as there is now. But it’s much more economically beneficial now to just rotate corn and beans, despite losing the benefits of those rotational practices. The root systems, vegetation and oats were holding the soil better then, and the potential for erosion was about a third of what it is now in terms of annual tillage.

NWNL When did people become aware that they should leave crops in over the winter or that more chemical usage isn’t good? How did such changes progress?

DARYL SMITH Generally speaking, when I was growing up on the farm in the 40s and 50s, we had rotational farming. We had much smaller farms and each farmer had more farm animals. It was just a more diverse system. Sometime in the 1960s, after I left the farm, we started converting into more intensive farming, tilling the soil annually to grow corn and soybeans, which increased in popularity after I grew up. I suspect no-till farming started in the 70s or early 80s. In order to stop plowing the soil under every year, we left the residue on the fields in the fall and didn’t till in the spring. Iowa farmers don’t change rapidly, but that pretty much caught on by the 80’s and has continued since then – but with more chemical utilization.

Palouse Also, when I was growing up, many farmers in hilly land would use contour farming and maybe even alternate strips of corn, hay and oats on a hillside – again to reduce erosion. But that was with smaller equipment and smaller fields, since there were more turns required. Obviously, it’s not as effective to plow or cultivate on the contour and plowing around the hill, instead of up and down the hill causes more erosion. So, now we’ve moved away from contour farming.

With our current, industrialized farming techniques, we use big fields, big tractors, large quantities and not too many turns so we can plant a lot of corn or till a lot of ground in one day. Yet we’ve taken out fence rows which provide wind breaks and maybe a little break for water erosion as well.

NWNL You’ve just mentioned water erosion. How would you describe the nexus of prairies and water.

DARYL SMITH The prairie has a very interesting relationship with water. When it rains, prairie vegetation intercepts a lot of the rainfall. As I mentioned, corn plants have adapted to collect water; but they don’t cover the whole area. Leaves and stems of other prairie plants collect and intercept rainfall. Thus, with a slow rain, that vegetation might absorb an inch of rainfall before it reaches the ground. Moisture drops can adhere to leaves and stems, slowly percolate, flow down or be absorbed by the plant itself.

The prairie’s interception of rainfall reduces the impact of droplets hitting the soil, whereas open soil between corn or beans allows droplets to start little erosion ripples right on impact. Prairies also have great capability in their tremendous underground root system. These roots are living, growing and dying – and creating a lot of openings and channels in organic matter that take in water via infiltration through the soil’s surface. Organic matter, created by roots, can absorb even more moisture. So, between the two, the prairie allows a lot of water infiltration and holds it, so it doesn’t run off.

I teach Prairie Ecology in our field station in Northwest Iowa, explaining how prairie vegetation naturally absorbs moisture that would otherwise run off cultivated fields. So, after a hard rain when water runs down residential driveways, I take my class into the prairie to see rainwater slowly moving downstream. And it may be 2 or 3 days before they see much increase in the flow of prairie streams.

NWNL Ah, yes! it is important to see “before and after” scenarios and what finally runs into the gutters. Last night, a deluge hit with rain flooding across the impermeable hard surface of the parking lot outside my motel room. I now have a great photograph to use to help people “see” runoff issues.

Daryl, there are many elements in any watershed, and each provides a service. Wetlands are one of those elements that fascinate me and intrigue me – whether coastal wetlands or upland wetlands. How do you compare the way the prairies filter pollution like acid rain with wetlands’ filtration services?

DARYL SMITH Prairies don’t collect as much as wetlands, because prairies collect water in one place. But basically, we’re talking about native vegetation in both places, rather than exotic vegetation that’s moved in. Prairie plants intercept rainfall themselves. Then that water infiltrates into the soil. Basically, the wetlands do the same. The primary difference is rainfall on prairie uplands and hillsides is transitory, whereas wetlands collect waters. It’s easy to visualize wetlands percolating and purifying waters, because they are actual basins, unlike prairie rains’ runoff on hillsides and uplands.

DARYL SMITH There are many ecological services provided by prairies and wetlands – and the forest as well. It’s hard to assign a monetary value to those ecological services, but we can assign a monetary value to human infrastructure via how much material was used and what it cost. For example, to control floods we build dams and know exactly what they cost. But we don’t know how to assess the value of ecological services provided by the prairie, or how much water is absorbed to reduce flooding.

In 2008, we had a major flood here in the Cedar Valley in 2008. Several cities here, particularly Cedar Rapids, were in national and international news then. But if we had had more prairielands in our watersheds, I think they’d have reduced the water that flowed into the rivers. Maybe they could have even taken 2 or 3 inches off the top of that crest, saving us a lot of money. But engineers and people who do environmental impact statements tell me we need more information on the ecological services provided by native vegetation and that we don’t yet have a good way of assigning a value to that. This is a challenge to the environmental community to better demonstrate the value of those ecological services.

NWNL Kenya’s Mara River Basin, one of our case studies, has assigned cost and monetary value to the value of its Mau Forest. With that, the Kenya Parliament okayed restoration of those headwaters. There were problems and hiccups in the process, but the Mau Forest is be reforested because the government grasped its fiscal value. You’re right that assigning monetary value is a critical step in our society to saving our species.

DARYL SMITH Well, I’m a bit biased. I think prairies don’t get enough respect because we think of trees being the salvation of humankind, rather than prairies. Prairie ecological services are frequently undervalued, compared to those of forests. Now forests are very valuable, don’t get me wrong. It’s just I think prairies are under-valued.

NWNL How do you evaluate the condition of our US prairie today?

DARYL SMITH In Iowa we have pretty good information on how much and how rapidly the prairie diminished. Prairie settlement began in Iowa in 1833, at the end of the Blackhawk War when the first settlers entered in the June of 1833, as part of the Blackhawk War settlement. People moved in from adjoining states, from further east, and of course from foreign lands. At that time, Iowa was at least 80% prairie, which was 28 million acres. By 1900, a tremendous influx of settlers converted this land to cropland with a tremendous development of agricultural technology, just as harvesters, John Deere’s improved plows and other technological tools were developed.

By the turn of the century, probably 95% of those 28 million acres was converted to cropland. Since then, we’ve plowed the remaining 5%, so that today we have less than 1/10th of 1% of native prairie remaining in Iowa. So, we reduced Iowa’s native prairie from about 28 million acres to less than 28,000 acres. Some people are aware of that magnitude of prairie reduction; but few know how rapidly that happened. Basically in 70 years – one lifetime – we converted almost all of Iowa from prairie to cropland.

NWNL How much prairie is left now? And what can we do to restore some of it?

DARYL SMITH Since most of the tallgrass prairie is now cropland, we have less than 28,000 acres of native prairie. To me, the obvious solution is to save those remnants for educational, heritage, water and any number of purposes. But that’s a very miniscule amount. I think we need a project to reinsert prairies back into our watersheds.

There’s evidence being gathered at Iowa State University now that if you have 10% of prairie in a watershed, you may reduce the amount of water runoff by 90%. I think a program to insert or reconstruct 10% of prairie in Iowa watersheds would have a tremendously reduce runoff in soil erosion.

NWNL Who do you turn to for support for that idea? Who could you partner with to insert 10% of prairie vegetation in all Iowa watersheds?

DARYL SMITH If I had the answer to that, I’d be some sort of a deity! I think it’s up to the political process. We have to convince the people it’s beneficial, before we convince our legislators. Bills have been introduced into the legislature to move in that direction. But they’re not getting traction because the legislators don’t see a political need yet. There has to be pressure from the constituents for this. We need to relate flood-recovery costs to the cost of putting 10% of prairie in the watershed. That would change people’s minds since money we spend in flood recovery could easily cover the cost of 10% prairie watersheds, even considering reduced “crop production.”

NWNL What about working with private landowners? I understand farmland here is owned by big commercial AG companies, but maybe there are enough private landowners to begin the process and show others how this works. Could that start the ball rolling and maybe end up in the legislature? How could an organization like the Nature Conservancy help?

DARYL SMITH The Nature Conservancy does wonderful things and I’m a strong supporter of their work in preserving land. But I think they would need to transition their approach to introduce reconstruction of prairie into the watersheds.

NWNL I’ve just interviewed Gretchen Benjamin with The Nature Conservancy [TNC] in Lacrosse WI. She shared that beyond acquiring land for preservation, TNC wants to study and address conservation of the entire water system. Gretchen explained that TNC has acquired a little bit here, a little bit here; but that it needs to be connected as a whole system. That’s what they’re doing now, after working with US Army Corps of Engineers and many stewards along the Upper Mississippi. They now want to take those solutions and the success down to the Lower Mississippi.

DARYL SMITH Well, TNC certainly has had success with their interaction with groups.

Yes, introducing prairies into our watersheds could be assisted by conservation agencies – perhaps TNC or others working with private landowners – to increase the amount of prairie in a watershed to reduce runoff. Some of Iowa’s Departments of Natural Resources have private land biologists working with landowners to improve watershed conditions. I’ve been impressed with watershed coordinators in Iowa in working with local landowners at the lower level and approving various conservation practices in the watershed.

I still think that we need an incentive for people to be sold on prairie reintroduction – such as reduced taxes if your land is in conservation. I don’t think you can use punitive means to do this. There needs to be an incentive to do the right thing and get some benefits. As my friend Bob Waller would say, “a win-win situation.”

NWNL That’s a term I’ve been using all week. Who’s Bob Waller?

DARYL SMITH He wrote Bridges of Madison County and was a dean on our faculty before his literary fame. There are little bright lights out there in the watershed. There’s a little work being done by watershed coordinators and by conservation agencies. It just seems like prairie reintroduction is such an overwhelming task.

NWNL Daryl, please explain your vision of your Tallgrass Prairie Center and its mission.

DARYL SMITH The Mission of the Tallgrass Prairie Center is “to restore native vegetation for the benefit of society and environment through research, education and technology.” Basically, we’re here to restore native vegetation to Iowa and perhaps other parts of the Tallgrass Prairie; to bring back some of our prairie heritage; and most importantly, to provide a practical means to help society.

NWNL What are your goals to help you meet your Mission?

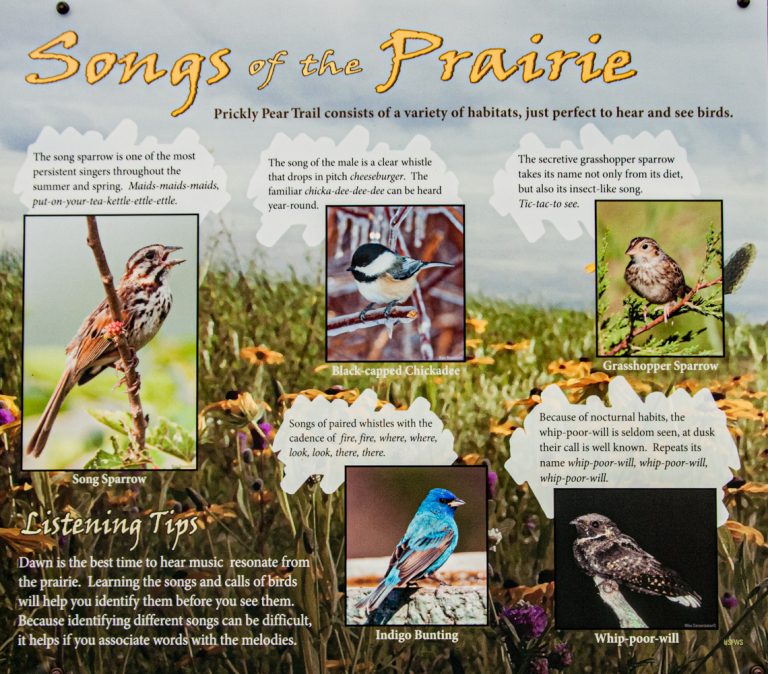

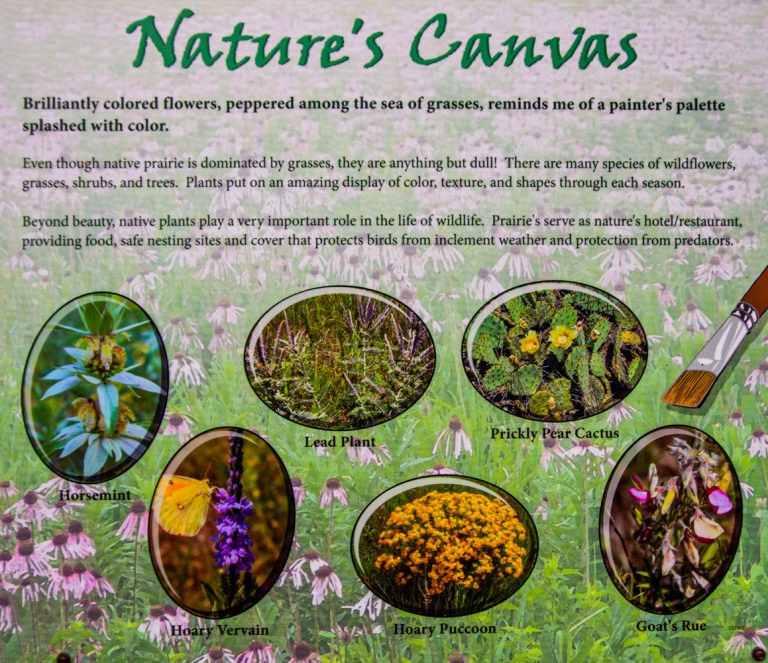

DARYL SMITH Right now, we work with the county to plant native vegetation along our roadsides as an alternative weed control instead of extensive mowing or herbicide use. We’re also developing native plants and providing seeds for planting more prairies. We’re looking at burning our prairie biomass for electrical generation and determining an appropriate mixture for that.

We’re seeking any means to reintroduce prairie vegetation back into the environment so we can once again cover a part, or parts, of the land with native vegetation that was once here. We’re not just doing this for aesthetic purposes, as nice as those are, but for practical purposes as well.

NWNL How strong is your focus on education? Isn’t that critical to convince people to buy into prairie re-introduction, be they lawmakers or private landowners?

DARYL SMITH We conduct technology workshops with the state’s roadside managers. We run workshops here at our Tallgrass Prairie Center on growing native plants and prairie reconstruction. About 10 years ago, we produced an award-winning film called “America’s Lost Landscape: The Tallgrass Prairie” that documents the tallgrass prairie as it was and the conversion of tallgrass prairie to crop land over 100-150 years. We have workshops for teachers. We produce public information releases and opinion pages in the local newspaper. For instance, I’m giving a talk at the Heritage Museum in Davenport next month to talk about prairie heritage.

We look at every opportunity to talk about prairies, have workshops on prairies and offer opportunities for people to learn more about the prairie. We also research better techniques for growing, planting and reconstructing prairie vegetation and on how we can adapt technology to do some of those tasks.

NWNL Do you make the seeds you grow available for planting? If so, how do you find your buyers? Who’s interested in doing it?

DARYL SMITH We don’t actually market seeds. We’re sort of the front end of R&D development. We produce small quantities of seed and make them available to native seed growers so they can increase the seeds and market them. We collect small quantities of native seed from prairie remnants across the street and across the state; and then we grow small amounts in our production plots for native seed growers. The largest purchasers, interestingly enough, are agencies like the Iowa Department of Transportation, a large purchaser of native seed for planting along primary highway roadsides, and counties that buy seed for seeding roadsides. As well, we sell to people interested in prairie reconstruction in general.

NWNL What is the profile of individual buyers of your seed?

DARYL SMITH There are a fair number of landowners who for various reasons want to plot a prairie on their land. Much of it’s aesthetic, but some are pheasant hunters or others who want good cover and food for pheasants and local game. There is also the Conservation Reserve Program – a federal program that allows seeding of native vegetation, particularly on highly erodible land so that it can reduce the amount of soil erosion. A number of prairie grasslands planted for that. Unfortunately, with the high demand for ethanol and corn right now, some of those CRP lands are being reconverted back to row crops.

NWNL Who are the people who’ve reconstructed prairies? In one interview you talked about growing interest in connectivity and migratory corridors and how the prairies actually can do quite well. Apparently, gene-pool stagnation isn’t a huge issue, so that even a little prairie here and a little prairie there works. Is that right?

DARYL SMITH Well, our Center encourages all who want a prairie on their land or want to help someone plant a prairie. If we can get enough small prairie plantings across the land and state, we can connect or merge those with larger prairie plantings. Even remnant prairie plantings can hopefully someday become corridors between these prairie remnant areas, creating a much larger mass that’s more viable. However, remnants isolated for a number of years risk some genetic degradation, which could ultimately lead to the demise of the prairie.

One concern is that we are maintaining living museums with these remnants. But if we start reconstructing prairies near remnants, then we can create a statewide, or at least large-area corridors and conduits, to sort of form a mosaic of prairie within the landscape. That plan can be very beneficial for vegetation and animals as well. One thing we do in our seed production is to collect seed from 10 to 20 different sites in northern Iowa; so, in a sense, we are reinvigorating those more isolated remnants. Some purists who want to maintain integrity don’t like that particularly, but I think it introduces the possibility of increased vigor, as more of that seed will germinate and maybe some isotypic variation from one site to another will ensure its survival.

NWNL How do you spread your philosophy on corridors and the importance of maintaining vigor in remnant prairie stock?

DARYL SMITH In a major speech I gave last summer at the North America Prairie Conference in Winnipeg, Canada, I discussed the history of prairie reconstruction as a bridge to the future. Prairie reconstruction was somewhat of a late starter. It began at the University of Wisconsin/Madison, when Aldo Leopold and others replicated some native Wisconsin ecosystems. Their first prairie was planted in the 1930’s and was probably the first effort for prairie reconstruction.

Since then, the Midwest has become a hotbed for prairie reconstruction, especially in Wisconsin, Illinois, Iowa, and Minnesota. Techniques learned over the last 60 or 70 years will benefit us in the future, including concepts like prairie for biomass; prairie in watersheds as we’ve discussed; and ideas from Wes Jackson at The Land Institute, using prairies as a model for his perennial polycultures.

These concepts will carry us into the next century. Frankly, I think this century will be the “Restoration Century;” because as we maintain at least some native vegetation, what we learn in the 20th century will benefit prairie reconstruction and restoration in the 21st century.

NWNL So, are we coming out of “The Dark Ages” – at least for prairies?

DARYL SMITH No, but we see a potential for getting out of the Dark Ages. In my darkest moments, I’m not too optimistic; yet I’m basically an optimist.

NWNL Unfortunately, people are saturated with bad news and many no longer listen. So, our NWNL website promotes how people can make a difference in their watershed. With that in mind, what is the minimum plot size for prairie restoration, and what’s involved for those wishing to create a prairie?

DARYL SMITH Well, you can reconstruct a prairie of any size you want – even a meter-square prairie in your backyard. That’s a miniscule prairie. Or you can enhance hundreds or thousands of acres. There’s a tremendous range in sizes of prairie restoration or reconstruction. So just choose a size that you can handle. For an individual, it’s going to be smaller than for a co-op, agency or conservation group.

Care basics begin by preparing your soil. Then you design a seed mixture appropriate for your soil type. After you seed the prairie vegetation, you undertake management techniques. First year, you mow to help control the weeds a bit. Usually, one year of mowing is sufficient to help prairie vegetation get established. Once that vegetation is established, you manage it like a native prairie, trying to keep wooded species from invading it. You may have to cut some trees and treating the stumps to keep out wooded vegetation. As well, hopefully you can burn it periodically. Fire is not the only way, but it is one of the best ways to manage prairie.

NWNL How is an eastern prairie different from a meadow?

DARYL SMITH A discussion of prairie versus meadow is just playing with words, because “prairie” is French for “meadow.” Both words are represent an opening in the forest where there’s more sunshine. In fact, with our roadside vegetation management, we open up much of that type of area to create native planting opportunities.

NWNL What are necessary weather and other parameters for prairies?

DARYL SMITH Probably on the east coast, you’re not planning midwestern-style prairie. But there are openings in New York and New Jersey woodlands with more sunshine. While they may not be midwestern prairies, they could probably have some grasses and forbs that are components of prairie vegetation, good to use for landscaping or planning a little plot. Unfortunately, it’s a lot easier to order seed from the Midwest where we have larger quantities of seed. But we don’t encourage that. Maybe I’m somewhat of a purist, but I would collect seed in New York to plant in New York.

NWNL I agree it’s important to stay native, and local.

DARYL SMITH Lady Bird Johnson agrees with that too.

NWNL You took that comment right out of my mouth. I was just going to ask about the role of Lady Bird Johnson – our US “First Lady” in the late ‘60s – in this this awareness of the value of wildflowers….

DARYL SMITH I think Lady Bird was a very strong proponent. I’m not completely enamored with her Texas program, but it had some good elements which she introduced nationwide. She was once at a talk I gave on roadside prairie strips. I think Lady Bird played an important role particularly in roadside beautification. It’s grown since then, but she kicked it off by saying, “We want Texas to look like Texas.”

NWNL In some ways, the long-term impacts of work were as almost as important as some of her husband’s achievements. At least, it was very significant. Speaking of inspiration, what else can you share to encourage gardeners to try prairie reconstruction?

DARYL SMITH We’re now trying to launch a Plant Iowa Native program. It’s in an embryonic stage; and other states with similar programs are in various degrees of development. We hope people will think about native plants when they buy plants for their landscaping of yards and other places, including commercial buildings as more landscapers are doing native landscaping. If we connect growers with native landscapers, we can increase availability and plant materials. We have a high hope for Plant Iowa Natives.

NWNL Are you saying each of us can help save native plants by asking our nursery for native plants?

DARYL SMITH Yes, anybody can capture a bit of “original Iowa.” And once they do that, they’ll be more aware of other projects using native plants.

NWNL How do we get our nurseries, both in Iowa and across the nation, to carry native plants?

DARYL SMITH Well, how do you get people to buy a plant? It’s marketing. We just hired a marketing student to work on that, because I’m a prairie ecologist. I’m interested in marketing and can provide basic plant information, but I need someone help us with that effort.

NWNL Should we advise consumers to look for and request native plants in their nurseries?

DARYL SMITH I’m sure nurseries will start handling native plants if enough people want to buy native Iowa plants. Not enough people do now, so we must persuade people to do so. We should brand our native Iowa plants – perhaps with a particular logo, or a little display talking about native plants and how to plant them. Maybe our little Plant Iowa Native corner ultimately will become a big corner.

NWNL You’ve had experience in leading seed nurseries to provide for increased native seed demands…

DARYL SMITH It wasn’t easy! Shortly after our roadside program started in the late 80’s, we realized there wasn’t enough native seed available. So, we started to collect seed per a well-considered ecological plan. But native seed-growers, when encouraged to sell our seed, would say, “Well nobody’s buying this native Iowa seed. We can only sell cultivars of this native seed. There’s just no market for it.”

Then we went to the Department of Transportation to suggest they plant native vegetation along roadsides because it would reduce mowing and the amount of chemicals used. They said, “Nobody’s selling the seed.” Seed growers said, “Nobody’s ordering the seed.” We had two interested groups, but we couldn’t get them together. They never fully believed in us. Finally, we got a grant through the federal enhancement funds started originally by Lady Bird, to buy native Iowa Source-Identified Seed for the Iowa counties to plant in the roadsides.

Growers eventually saw the demand, because we annually bought $300,000 to $400,000 worth of seed. That was a profitable venture for us, but it took that grant for us to get it started. So, I went from an ecologist to controlling part of the market. And I can safely say after 15 years that the project was successful. We met our original goals of increasing the native seed available at a competitive price. But it took that grant to push it over the top.

NWNL What a story! Congratulations. Going back to that individual consumer, how can they find nurseries that have native plants? Is there a website?

DARYL SMITH Yes, visit our Plant Iowa Native website.

NWNL Will that be a model for areas beyond Iowa?

DARYL SMITH We plan to introduce our Plant Iowa Native project to nursery people and landscapers, and then get a program to serve the public. Our website also lists service providers who will plant a prairie larger than a backyard prairie and who will burn prairies for you. Soon, we hope nurseries will provide those lists. For now, people can go to our Plant Iowa Native website for this information. Soon, we’ll add more educational materials on how to plant a prairie, based on expertise in a book we published about 3 years ago on prairie restoration and the Upper Midwest tallgrass prairie.

NWNL Do you see the Plant Iowa Native website and project as a model for all states?

DARYL SMITH Yes, we could be a model for other states. Some states are already doing similar projects. Ours may be more comprehensive than others and could be a model, just like our Natural Selections Program that collected seed from local Iowa remnants for native-seed growers. That model could work in any state, just as people from Connecticut collect seed from the openings there; grow that seed; and make it available for roadside plantings and other types of meadow restorations.

NWNL Your last comments were a brilliant way to end this interview, except I have more to ask you … starting with the “I” word. How do you keep invasive species out of your prairie mix? Is it a problem? It seems invasive species exist in every watershed.

DARYL SMITH Yes, invasive species are a problem everywhere. Regarding native vegetation, invasives can move into such plantings and take it over. We must be constantly vigilant to keep invasives out. Many people think, “Well, I planted a prairie and now I can just let it go.” Un- uh! They have to manage that prairie. They have to keep native and non-native woody invasives out – as well as exotic species that move in.

NWNL What specific invasive species are problematic in Iowa?

DARYL SMITH One of the biggest problems in wetlands is weed canary grass that has moved in, because it does very well under siltation conditions. It has taken over some excellent native plantings and now there is a constant battle to keep out.

We fight invasive species all the time. There’s no magic bullet to control them other than hard work. Even with shared knowledge and best techniques to keep them under control, they’re going to be there. They’re going to increase because we disturb existing vegetation more, which creates the opportunity for invasives to move in more easily. Our fight against invasives is a worthwhile battle – but an unending battle.

NWNL Regarding another universal threat, what will happen to prairies regarding climate change? Are they more resilient in the face of climate change?

DARYL SMITH Prairies probably have more adaptability to increased temperatures and less moisture and probably can maintain their viability better than woodlands do under those conditions. But they can suffer too. Obviously, the tallgrass prairie requires more moisture than mixed-grass or short-grass prairie. In long, hot and dry droughts, tallgrass prairie will suffer more than mixed-grass or short-grass prairie. But they won’t suffer much as wooded species will.

NWNL Is there any historic precedence to support this?

DARYL SMITH Yes. About 4,000 to 7,000 years ago, during what they call the hypothermal period, temperatures were much higher and prairies in those hot and dryer conditions extended perhaps as far east as New York. Since the last 3,000 years, it has been increasingly moist here and so woodlands are moving back. Probably if the Native Americans hadn’t done extensive burning in the last 3000 years, the woodlands would have moved even further into what’s now the eastern part of the tallgrass prairie.

NWNL Where can we visit prairie remnants? Are they listed on your site?

DARYL SMITH We don’t have that on the site; but the State Preserves Advisory of Iowa has a booklet of these preserves, and their website should have a listing and a book on those Iowa preserves.

NWNL My last topic for you to address is the role of bison on the prairie.

DARYL SMITH There were not as many bison in the tallgrass prairie as there were further west; but the bison on the tallgrass prairie were a keystone species of the prairie as they moved around. They wouldn’t stay in any one area for a particular amount of time, but they were fairly large herds, grazing a lot of the grass, trampling a lot of the soil, and leaving a lot of nutrients from their feces and urine. They really impacted native vegetation and disturbed it for a period of time. But it would recover before they came back again. While an important keystone species in the tallgrass prairie, they were not as major a component as they were in the prairie further west.

NWNL Does their behavior and role in the prairie ecosystem provide a model for how rotational livestock farming can work? In Texas, I’ve heard people say that cattle farming is okay if you rotate your herds.

DARYL SMITH The movement of the bison certainly can be a model for allowing the prairie to recover. With rotational grazing (or “fly-grazing”), they move their cattle for a period of time and then move them on again. Another recent prairie-recovery technique is “patch-burn grazing,” which works for bison or cattle. As you move bison or cattle around, you also move fire around, since they are attracted to recently burned areas where grasses are green, young and succulent. Bison and cattle graze that vegetation down almost to the ground, moving on perhaps the next year, after you burn another patch.

NWNL There’s an interesting correlation to both African pastoralists’ traditional savannah management techniques and East Africa’s national parks’ current efforts to support the wildebeest migration.

DARYL SMITH Well, wildebeest are the “Bison of the Savannah.” However, a lot of people interested in prairie preservation do have a very negative feeling towards grazing cows. The problem is that we fence the cattle in a particular area and leave them there too long. They compact the ground and then destroy the prairie vegetation. Many who were involved early on in prairie preservation developed a negative reaction to cattle grazing if they came from places with heavy cattle grazing. But if cattle are managed properly and not left too long in an area, they don’t overgraze. Moving them around periodically can actually be a helpful tool in maintaining the prairie.

NWNL A win-win for cattleman and prairie conservationists.

DARYL SMITH Yes, that’s a win-win, again.

NWNL Daryl, that is a positive note on which to end. I appreciate your letting me take up a lot of your day to record your amazing store of tallgrass prairie information.

Posted by NWNL on June 22, 2021

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.