Protecting White Sturgeon

Columbia River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Columbia River Basin

Mike Parsley

US Geological Survey/USGS; Member of Technical Working Group of Upper Columbia River White Sturgeon Recovery Initiative (UCWSRI); Affiliated with Columbia River Research Laboratory of the Western Fisheries Research Center

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director and Photographer

Besides enjoying walking his dogs on the sandy flats of Hood River, Mike Parsley is a research biologist for USGS and a member of UCWSRI. In so doing, he became fascinated with the Columbia River’s awesome white sturgeon. Mike says one important facet of his job is to dispel myths surrounding this unusually large freshwater fish.

NWNL UPDATE: Retired from USGS in 2014, Mike co-authored a 2016 paper on the status of White Sturgeon within their range. In 2024, he wrote NWNL, “We’ve not yet seen recovery of Canadian sturgeon listed under Species At Risk Act – nor in Idaho or Montana’s Kootenai River where listed under ESA. However, we’ve made great progress boosting juvenile fish numbers in several Columbia River reaches by capturing wild larvae, rearing them in hatcheries, and releasing them at a size when survival is pretty well ensured. We also use traditional broodstock collection, egg and sperm take, and rearing in hatcheries to boost juvenile White Sturgeon numbers in the Kootenai River and some mid-Columbia River reaches.”

STURGEON RESEARCH

AN UNUSUALLY LARGE FISH

THE LIFE OF A STURGEON

THE HISTORY OF STURGEON

STURGEON IN THE COLUMBIA

STURGEON STEWARDSHIP

STURGEONS WORLDWIDE

STURGEON HABITAT CONDITIONS

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

NWNL Mike Parsley, I am looking forward to chatting with you about the Columbia River’s famed white sturgeon. How did you first get into that niche?

MIKE PARSLEY When I started working with sturgeon in 1987, there was little sturgeon research going on, although the States and Tribes knew the sturgeon here were an incredible resource. This is one of the few places in the world where one can still harvest sturgeons. There was an obvious need for some basic biological information, so I’ve worked with white sturgeon ever since then.

Primarily I work with the very young stages of their growth, from spawning on through what we call the “age zero fish,” or the “young in the year” fish. We need to have those fish to mature into adult fish 20, 30, 40 years down the line. That’s been challenging, but it’s an interesting river to work in.

Today, sturgeon populations across the world are declining rapidly, but out here on the Columbia we still have a pretty good population of white sturgeon. We have recreational angling and harvests. We have tribal subsistence and tribal commercial fisheries; and we still have a small commercial fishery in the lower Columbia River for white sturgeon.

NWNL Tell us about this fish – it’s both huge and strange looking!

MIKE PARSLEY It’s the largest fish to reside in fresh water in North America. There are reports of fish being 20 feet long. Historical photographs show fish that are at least 15 feet long. We’ve seen fish in recent times that are over 12 feet in length. They are an ancient fish, basically unchanged for about 200 million years.

NWNL How do you know that?

MIKE PARSLEY From fossil records. Some people call them primitive. They aren’t primitive, per se. They’ve developed a relatively resilient life strategy that has meant they didn’t need to change over millions of years.

I work with white sturgeons found on the west coast of North America. We have two species of sturgeon here – a white and a green sturgeon; and eight species across the U.S.

NWNL How do you distinguish white from green sturgeon?

MIKE PARSLEY It’s easy visually since the greens are a darker green color and tend to be more estuarian. They’re found in coastal rivers, more than white sturgeon. We don’t find them up this far up the Columbia here at Hood River. They are slightly smaller than whites; but they still can get to be 6 or 7 feet long.

NWNL On the size of white sturgeon, I’ve heard of 20-foot sturgeon coming down the river. But you’ve only recorded sturgeon up to 12 feet. Are they declining in size? If so, is there a cause?

MIKE PARSLEY There’s a definite decline in numbers in parts of this Basin. Assessing the cause is difficult since it’s hard to catch and sample a fish that big. They are just too large to handle.

However, we have decent reports of fish 15 to perhaps 17 feet that reputable folks and state agency folks have seen while conducting other sampling on the river. So, we think there are a few fish out there that are that size. Not every fish reaches 15 or 20 feet; but if an occasional fish that size ever washes up on a beach or gets captured, it gets attention. It doesn’t take many fish that size to get rumors flying about how big they get. But the six, seven, eight-footers are much more common.

NWNL Let’s put aside size for a moment and discuss the nature of sturgeon. I’ve heard white sturgeon migrate upstream from the Pacific Ocean, like the salmon.

MIKE PARSLEY Actually, that’s false. Many people say white sturgeon are anadromous, and thus, like a salmon, they go to the ocean, mature for a few years, and return to fresh water to spawn. However, a white sturgeon’s life cycle is entirely in fresh water. Those downstream from Bonneville Dam, where there is easy access to the ocean, will on occasion go to the ocean. But going to salt water is not part of their life cycle. They are quite different from salmon.

NWNL Perhaps in sharing the river with salmon, sturgeon are mistakenly lumped into that migration pattern.

MIKE PARSLEY Well, we just don’t understand a white sturgeon’s life history as well as we understand a salmon’s life. White sturgeon have not garnered the attention that salmon have.

NWNL What’s the history of sturgeon in this ecosystem? And how have they been valued by the people on the Columbia. Salmon are part of an incredible story and supply many nutrients across whole Columbia River region. Do sturgeon play a similar eco-role in this watershed?

MIKE PARSLEY All fish adapt their life strategies to meet seasonal currents’ ebbs, flows and temperature regimes. The balance in the Columbia River Basin is such that two wholly different species of fish have learned how to adapt to life here.

However, in the late 1800’s, sturgeon were viewed as a nuisance to salmon fisheries. Because they are so large, they would tear up the salmon gear. So commercial fishers would just toss them up on shore. They’d do anything they could to get rid of sturgeon.

But, as caviar became fashionable, sturgeon became important and their meat became more accepted. On the East Coast their meat was called “Albany beef.” Relatively inexpensive, sturgeon provided a large source of protein in these fisheries. In the late 1880’s, commercial fishermen targeted sturgeons and literally decimated their populations across the country. By the late 1880’s, white sturgeon were over-harvested throughout the basin and into the Snake River. Their numbers plummeted and I believe it wasn’t until the 1930’s that states started to regulate their fisheries. Ever since then, there’ve been a series of regulations to bring them back their former numbers. Fortunately, restoration of sturgeon fisheries here in the Lower Columbia have been quite successful.

NWNL Your positive report on the restoration of today’s sturgeon population leads me to ask what factors determine that? Is it water quality? If so, what sources might pollute their water – those upstream, or those seeping into the river from local riverbanks?

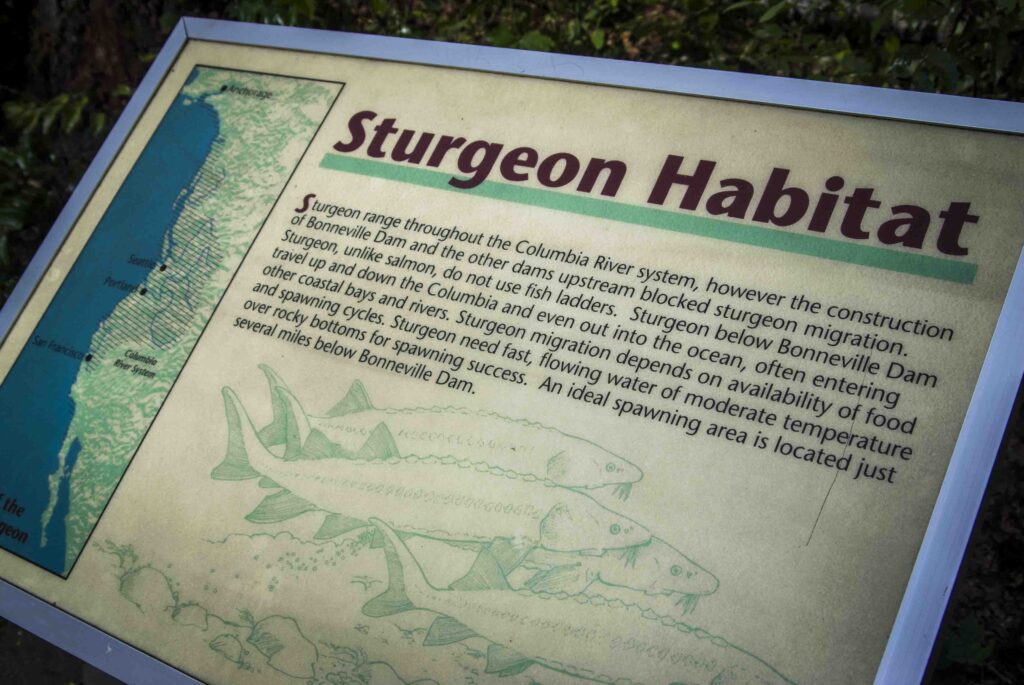

MIKE PARSLEY Probably one of the largest things to impact sturgeon here in the Lower Basin is the sheer presence of dams. There’s a chance that dam construction has inundated their spawning areas. But we still have sturgeon spawning downstream from every dam that we’ve looked at in the Columbia Basin.

NWNL What about residential development along the river. With building booms and development, is the Columbia losing trees along its riverbank? I heard a loss of trees upstream has affected the salmon who need tree shade to lower water temperatures. Has that issue bothered the sturgeon here in the Lower Columbia?

MIKE PARSLEY Probably not so much. Though we have seen in the Upper Basin particularly dam’s water storage can shift the time regime of temperatures. Much of the time, water storage makes the river’s water much colder in the spring when sturgeons spawn. If protracted, that could delay spawning. Those are some of impacts we see for sturgeon.

Sturgeon habitat is in the main stem, so they are not impacted as directly as salmon are in the tributaries, but the impacts are still there. The dams have raised pool levels, reduced water velocities of extensive reaches, changed substrate characteristics in the reservoirs, allowed areas to silt in and such. But we still have spawning downstream from literally every dam in the basin.

NWNL Do you see their population numbers going up, down or staying the same?

MIKE PARSLEY We hope at least to see them stay the same. In the late 1980’s we had low salmon numbers. Once the many anglers could no longer easily fish for salmon, they targeted sturgeon, creating a short spat of over-harvesting of sturgeon. Managers clamped down on that relatively quickly by instituting quotas and such. I think the managers are doing a decent job in maintaining the status of sturgeons and restoring their numbers somewhat. We still have decent fisheries in the Lower Columbia River, for both tribal subsistence and commercial fisheries.

NWNL What about in the Upper Columbia?

MIKE PARSLEY The Upper Columbia is a different story. There populations are constrained behind every dam basically. Sturgeons do come downstream when the spill gates are open. But they can’t get back upstream through the fishways. The fishways were engineered for salmonids; and since sturgeons are much larger, they can’t use those fishways.

Further up in the basin, the sturgeon populations are a bit more precarious. In 1994, the Kootenay River sturgeon, geographically isolated about 13,000 years ago, were listed as endangered. That population used to be an important resource for the Kootenay Tribe and other folks in that part of the basin. The Snake River is well known for its catch-and-release fishery for sturgeons and provides good recreational opportunities for guided trips through Hell’s Canyon. In other parts of the Middle Columbia up to Lake Roosevelt, we’ve seen declines in the populations, but restoration efforts are underway.

NWNL How do you restore sturgeon numbers, given the problem of raised water levels?

MIKE PARSLEY We are trying to understand what conditions sturgeons require to reproduce. We first restricted harvest in those areas. Targeted catch-and-release angling for sturgeons in those fisheries has been restricted. We’re working with hydro-power operators to provide better flows and temperatures during the sturgeons’ spawning period to get natural reproduction reestablished in those areas. To further increase the numbers, we have started some sturgeon hatcheries from which we release small numbers of juvenile sturgeons into the river.

NWNL I’ve heard people are concerned that sturgeon have lost their natural reproduction process and that that there is something amiss probably due to dams or their impacts during the time of spawning.

MIKE PARSLEY Problems happen either during the time of spawning, or shortly thereafter. When we search for signs of sturgeon spawning, we often find the eggs. So, we know they are depositing eggs and that they are viable. If we bring those eggs into a controlled environment, they’ll hatch and those small sturgeons will develop correctly.

That doesn’t mean that there aren’t other issues. There are thoughts that the dams have reduced current velocities and therefore the embryos aren’t being distributed downstream properly. There are thoughts that perhaps by shifting temperature regimes in the river, the food young sturgeons need isn’t available when they need it or where they need it. There are always worries over contaminants in the river that may not kill sturgeons directly, but that might affect the performance of these very small fish. They may look healthy, but if they can’t swim correctly, or if they are impeded in some other way that they’ll succumb to predation or other factors.

NWNL Have you isolated which contaminants might be causing such an affect?

MIKE PARSLEY I work with folks who look into that, but I am not a contaminants person.

NWNL Are sturgeons around the world having problems? How do white sturgeon in the Columbia River Basin compare to Russian sturgeon which produce the beluga caviar?

MIKE PARSLEY By and large, sturgeon populations across the world are in serious decline.

Regarding the Russian sturgeons in states \around the Caspian Sea, there are a variety of reports addressing that. Their issues center on habitat loss, heavy pollution and much overharvest, intense poaching, and many unregulated fisheries. All these things coalesce to cause problems for sturgeon populations. Unfortunately, because they are so long-lived, it takes a long time to bring these populations back from the brink.

NWNL What is their normal lifespan?

MIKE PARSLEY White sturgeons will commonly live for 40, 50, or 60 years. We have some fish we believe have lived to over 100 years old. They are very long lived, but not necessarily slow growing. They grow very fast when small, but then they take a long time to reach maturity. A female won’t start spawning until she’s 10, 12, or 15 years of age. Males will start spawning a little bit earlier than that.

NWNL Their cycle is much like humans, eh?

MIKE PARSLEY Yes, they are sort of like humans, and they take a while to reach puberty.

NWNL Have you learned anything about Caspian Sea sturgeon that might relate to problems that the white sturgeon face in the Pacific Northwest. Is there any cross current back and forth about solutions and problem-solving methods?

MIKE PARSLEY There is quite a bit. We work with Russian colleagues on how they restore their fisheries, and visiting scientists come here to see how we work with our fisheries. The cultures are quite different, so it has been quite interesting. My colleague Geogy Ruban in Moscow recently published a book in Russian which is the only monograph I know of on Siberian sturgeon. A couple of years ago, I worked with a University of Washington student to translate that book into English. It was quite an endeavor and quite interesting to see what work they’ve done with some of their species.

NWNL How does it compare to the work that you are doing?

MIKE PARSLEY Quite similar. The Russian model has focused more towards hatchery production and propagation to restore their fisheries, more than the US, but the problems that were identified as decimating the Russian stocks are very similar to some of our here: primarily habitat loss, pollution and areas blocked by dams preventing sturgeons from migrating to either productive forage areas or productive spawning areas.

NWNL So even though they don’t go out to the sea like salmon, they do migrate?

MIKE PARSLEY Yes, they do migrate. They migrate seasonally for forage for over wintering, and things like that. By putting in all these dams, we’ve constrained the amount of river within which they can move.

NWNL And it seems the fish passage in these dams don’t accommodate the sturgeon?

MIKE PARSLEY By and large – no. The one exception is the fishway at the Dalles Dam that typically passes anywhere from several hundred to just over a thousand sturgeon a year. We conducted a study there a couple of years ago. You might think all fishways in the Columbia Basin were constructed the same, but this one fish way was built substantially larger than the others. Thus, its submerged orifices are about twice the size of those in other fishways. We believe that is why this fishway allows sturgeons upstream.

NWNL Is there any chance of modifying some more fish passages of dams on this river to accommodate sturgeon?

MIKE PARSLEY I would like to say yes. I think it might happen at some point. But right now, sturgeons aren’t listed as endangered or threatened in this part of the basin, so there’s no big impetus to modify these dams. There’s also a question as to whether those modifications will be good. According to what we call a meta-population theory, there might be some advantages to trapping sturgeons to from a management standpoint.

NWNL So you’re able to monitor their population?

MIKE PARSLEY Well, if you modify one dam so fish can swim upstream, but that area upstream of the dam isn’t suitable for them, then you’ve allowed fish to move into an area where they could be harmed more than if they weren’t allowed into that area. We must take questions like that into consideration.

NWNL That’s true with the salmon too, right? I know that many people who remember salmon upstream want those salmon back, as part of their culture and their spirit and for nutrient-enrichment of the whole ecosystem. Yet, indeed, some scientists say we don’t know whether those waters are still good for the salmon. There may be too many changes now – due to dams, pollution, development, and climate change. It’s a tricky question! Do we spend money to build fish passages in dams all the way up into Canada? Will they survive if we do that?

MIKE PARSLEY Society must realize we’ve made relatively permanent changes to this landscape. We are working within those changes to maintain and restore our fisheries to our best ability.

NWNL Does Bonneville Dam have a fish hatchery for white sturgeon?

MIKE PARSLEY No. They don’t work with white sturgeon, per se. They have a Visitor Center, for viewing some white sturgeon. That’s really good, because white sturgeon are difficult to view in the environment, especially as the river is just way too deep. So, the sturgeon at Bonneville Dam allows the public to get really close to sturgeons, learn about their life cycles and read about their role in the ecosystem. But the Bonneville hatchery itself doesn’t work with white sturgeon.

NWNL So the sturgeon that are there are captive?

MIKE PARSLEY Yes, but I recommend you see “Herman the Sturgeon” at Bonneville Dam.

NWNL In the Columbia River is there a gap in the population age-wise?

MIKE PARSLEY We see many ages represented out there. One thing we are trying to come to grips with is what is a good age structure for sturgeons in the Columbia, since they are so long-lived. Do we want a lot of 4- to 7-year-old fish? Do we want a lot of 20- to 40-year-old fish? Or do we want a lot of 40- to 60-year-old fish? We don’t know because we don’t have much historic information on stock structure for sturgeon populations.

NWNL Can you get any information to draw on from tribal cultures and their memories and oral histories?

MIKE PARSLEY It’s a little sketchy. We know sturgeon have always been important to the tribes all along the West Coast. They were harvested and culturally very important in the tribes. I don’t believe they were as important here in the Lower Columbia as the salmon. But for tribes further away from the salmon, sturgeon have been important, as with the Kootenay tribes further upriver.

NWNL Was that because they were present year-round since they didn’t migrate down to the ocean?

MIKE PARSLEY I think so. Fish there were always available for harvest. Looking at some of the middens, some good archeological papers coming out of California‘s Sacramento-San Joaquin Basin show that green and white sturgeon were a part of the diet in those tribes.

NWNL What does sturgeon taste like?

MIKE PARSLEY It’s very good on the grill, very good fresh. If you’ve had swordfish or shark, it’s a similarly firm piece of meat. It’s not a white flakey fish like bass.

NWNL That’s why it’s called Albany beef on the East Coast.

MIKE PARSLEY Yes, the Atlantic sturgeon that was harvested was sold it in bars and other places as Albany beef.

NWNL How would you compare Hudson River sturgeon with Russian sturgeon, the Caspian Sea species? I’m interested partly because the Hudson estuary is terminus for the Raritan River, another watershed NWNL is studying.

MIKE PARSLEY Well the Hudson has two species of sturgeon – the Atlantic sturgeon and the short-nosed sturgeon. Just like every other sturgeon population, they went through a period of extreme overharvesting followed by a slow rebound. There is some indication that the Hudson River sturgeon are bouncing back a bit faster than people expected.

NWNL What is the reason for that?

MIKE PARSLEY The sturgeon rebound in the East Coast rivers – and the Hudson in particular – is probably due to reduction in pollution.

NWNL Do you attribute that to the work of Hudson Riverkeeper?

MIKE PARSLEY I attribute that to the work of a lot of different people, going all the way back to the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act. The short-nosed sturgeon was listed as endangered a while back, and that curtailed harvest immediately.

NWNL Has the Hudson River clean-up had greater success than that of the Columbia River?

MIKE PARSLEY I’m not that familiar with the Hudson River, and the issues are different. The Columbia River is polluted, but never polluted to the extent that East Coast rivers were. Every river has its problems, but the East coast rivers were on fire in some places [e.g., the Cuyahoga River in Ohio in 1969]. We haven’t seen that level of pollution here. We may have more insidious pollutants out here, but industrialization along East Coast rivers is far greater than ours out here. Much of that is being addressed or has been addressed.

NWNL But here, you have the heavy metals.

MIKE PARSLEY Yes. We have metals from mining, particularly in the Upper Basin.

NWNL Do heavy metals affect sturgeon?

MIKE PARSLEY We don’t know. And you’ll hear that a lot from me….

NWNL Are you getting good financing for study?

MIKE PARSLEY No. That’s a tricky question in a way. No, we don’t get the attention that endangered fishes get out here in this part of the basin. Salmon, but also other species – bull trout, lampreys were petitioned for listing, so they received a spat of funding there in the last few years aimed at addressing that petition.

NWNL And a lack of funding for the sturgeon then is because it’s not quite endangered?

MIKE PARSLEY It’s hard to argue that they need to put a lot of money into sturgeon research when we do have endangered species. Fish that are on the brink of becoming extinct, at least here in the lower part of the Columbia. We are comfortable that we can maintain sturgeons, at least at the existing populations. We’re still learning a lot about sturgeon and have a lot of research going on into their early life history. There is also research going on regarding the effects of contaminants on sturgeons, but we don’t have the need for immediate action that we do with other endangered species.

NWNL What would you like to see happen to protect this river?

MIKE PARSLEY It’s a well-monitored river and every effort to restore endangered salmonids will likely benefit sturgeons, since the two species co-evolved together in this river. If flows are modified to improve juvenile salmonid survival, that will likely help sturgeons as well, because juvenile salmonids go out to the ocean when sturgeons are spawning. That’s my one hope.

Posted by NWNL on November 26, 2023.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.