Protecting NJ’s Water Supply

Raritan River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Raritan River Basin

Ken Klipstein

New Jersey Water Supply Authority

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director and Photographer

Peter Berman

Video Producer

Julie Eckhert

Video Editor

Ken comes from the Upper Raritan where he has been very involved on a volunteer basis working on the Tewksbury Land Trust Board. In full disclosure, a few years after this interview, I joined him on that Land Trust Board and so I can vouch for his knowledge and passion for conservation. Ken also has worked across the Garden State of NJ, not just in the Raritan Basin. He’s held jobs with NJ Dept. of Environmental Protection and now with NJ Water Supply Authority. NJ is lucky to have his commitment to watershed conservation.

LANDSCAPE & WATERSHED CHANNELIZATION

CHANNELIZING LEADS TO POLLUTION

NEW POLLUTANTS – PHARMACEUTICALS & MORE

COMPETING INTERESTS & CLEAN WATER COSTS

COMMUNITY STEWARDSHIP

STEWARDING WATER SUPPLIES

PUTTING IT SIMPLY

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

NWNL Ken, given all your experience in watershed management work statewide, I am curious about the opening statement in your presentation. Can it be true people did use dynamite to blow up our rivers?

KEN KLIPSTEIN In fact, they did. This is something that’s been a joke amongst our national stream-restoration community. The comment was circulated by a gentleman that used to work for the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers who now goes around giving stream-restoration courses.

JULIE ECKHERT What was the point of blowing up a stream?

KEN KLIPSTEIN As I said in my remarks, I think the basic philosophy of engineers hasn’t really changed that much. The point has been to move the water off the landscape as quickly as possible and into the stream to develop the land. So, that was the engineering approach that was taken, as they recommended, “Get that water to the stream as quickly as possible.” When you start doing that, you need more capacity in the stream, so blowing up a stream was one of the techniques that was used.

NWNL And what was the ultimate effect of doing that?

KEN KLIPSTEIN Channelization and the term “hydro-modification.”

NWNL How would you explain that concept to a 7th grader?

KEN KLIPSTEIN Hmmm. I was going to start with “ubiquitous hydro-modification”!

NWNL Oh, I’m glad you edited yourself!

KEN KLIPSTEIN “Hydro-modification” is simply modification of water over the natural landscape, or the channelizing of water to the stream. You see it everywhere. If you drive around the railroad trestles, you’ll see the way that railroad beds were placed across the landscape. They bisected the land of our natural watersheds.

NWNL Why is channelization a bad thing?

KEN KLIPSTEIN It’s terrible in that it disrupts the natural flow of the water and in effect causes more flooding problems. When it rains, rather than water being absorbed, it’s directed across the landscape. That causes much more “flashiness.” [”Flashiness” produces the possibility and consequences of flash flooding; a term that is more and more used, given the increased frequency of climate-change induced flash floods]. Rather than naturally soaking into the ground and spreading out, rains flow into a channel to go right to the stream. There are then big variations in that stream flow.

The more organization you get, the more of fluctuation you have. The Center for Watershed Protection in Maryland is one of the leading authorities studying this. Their research shows that the threshold is about 5% of pervious coverage in the watershed. When you get fluctuation up as high as 25%, you’re pretty much done. Nothing can live in such streams. Channelization causes all kinds of other problems, so this whole conversation on sustainability is about figuring out where that tipping point is – that balance is between our human footprint and the natural system. It’s somewhere!

The land is quite resilient, and technology offers ways to mitigate our impacts. But there is a tipping point. Today, we’re well beyond that – mostly because of the old techniques used in channelization. It’s very difficult to go back.

We’re not taking out railway beds that bisect watersheds or roadways. That number to me is staggering when you look at 6,600 miles of roadways in the Raritan basin. That’s 2 trips across the U.S. The road system we have acts as a conduit for our rainwater to move at a faster rate into our steams.

NWNL And in addition to causing flooding, that surging rainwater is also polluted.

KEN KLIPSTEIN Yes. It carries a lot of contaminates, sediments, nutrients. Those are the big ones that I highlighted and that we work on. We’re trying to trap and collect sediment particles and not let those pollutants get into our streams.

From our perspective as water-supply purveyors and providers of clean water, we want to minimize sediment amounts we see in the stream, or turbidity – as it’s technically called. Simply put, turbidity is cloudiness or muddiness in the water. It’s the opposite of clarity.

NWNL So, if this continues to happen, would we then turn on our faucets and have cloudy or muddy water?

KEN KLIPSTEIN No, treatment plants address that and take out all those things, but at a high cost. Treatment plants settle contaminants out of the water before they deliver it to your pipe.

NWNL What are your more recent concerns?

KEN KLIPSTEIN There are newer issues of water potentially running into contaminants like pharmaceuticals that are very difficult for water purveyors to remove. These are the new challenges we’re facing.

NWNL What, if anything is being done about that?

KEN KLIPSTEIN Well, there are now many studies examining levels of pharmaceuticals and other trace contaminants in the water; their health effects.; and strategies for removing them. There’s not much we can do since we’re not yet sure of health effects of pharmaceuticals in our water – but we are studying them.

For the most part, New Jersey’s water supply is very, very good. In the Raritan it’s extremely good.

NWNL After all this talk this morning, I became concerned about drinking this water.

KEN KLIPSTEIN Well, the Lower Raritan Basin is not used as a surface water supply. None of that water is withdrawn or delivered. Most of the water delivered to homes comes from the Upper Raritan where the water quality’s very good.

We’ve done a good job over time regarding source-water protection. Spruce Run and Round Valley Reservoirs were built in the 1960’s. They’re very well cared for — if I do say so, since I work for the company.

NWNL You mentioned one of the biggest obstacles to cleaning up the river is competing interests. Can you explain that?

KEN KLIPSTEIN Well, there are always competing economic interests, regarding how we use our dollars, what we want our communities to look like, and so on. Our system is based on home-rule structure and local land use decisions. Local land use policy is made at local levels; and they want good tax ratables and businesses to come into town. So, they’re always balancing those interests.

Going back to how the landscape changes when you pave it over.… When big box stores are built with large parking lots, we get closer to that tipping point. Technology can overcome some of that. I think new stormwater systems addressing parking lots and such are now technologically possible. So, we need cost discussions about storm water utilities. The problem is these advance treatment systems have a high cost of maintenance.

Collecting that sediment – that otherwise would go to the stream – means we must clean those systems, replace the filters and do such things. That’s not a high priority in many municipalities; and they don’t do a good job generally. Generally, towns are not adequately budgeted to clean out these systems on a regular basis. The more advanced the technology, the more maintenance will be required. So, it’s critical to discuss storm water funding.

NWNL You claim one of the pluses regarding the Raritan is that a lot of people care about this river.

KEN KLIPSTEIN I think it’s unique in my experience. Prior to coming to the Water Supply Authority, I was at DEP doing watershed management work statewide. The Raritan is such a great example, because it has three of the oldest watershed associations in the country, not just New Jersey. The Stoney Brook-Millstone Watershed Association is celebrating 60 years of doing land preservation, advocacy and education and the same with Upper Raritan Watershed Association/URWA in the South Branch.

Grassroots stewardship makes all the difference. At the end of the day, government regulations are about ordnances and how ordinances work. Unless people want to change their behavior, it’s going to be very tough to get to that point of sustainability.

NWNL What lifestyle changes should average people make to improve the river?

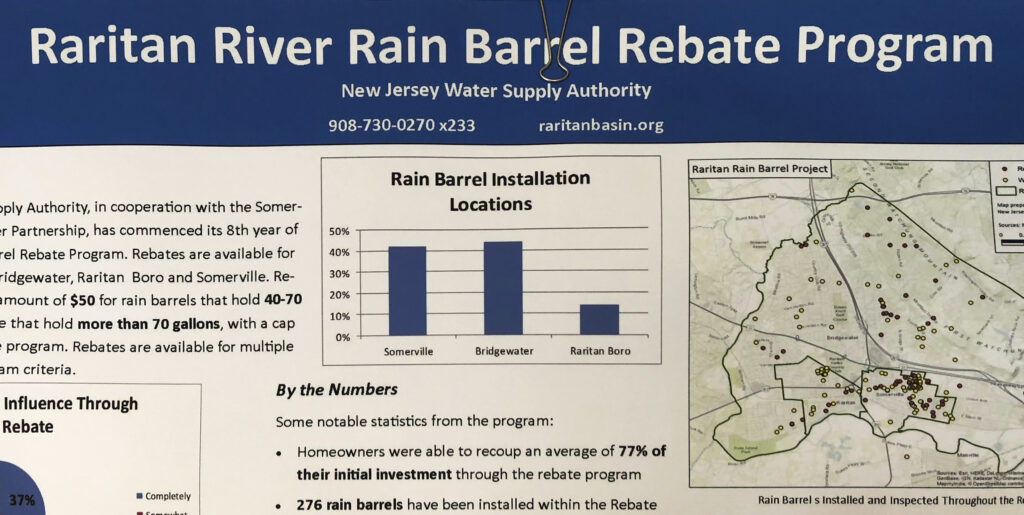

KEN KLIPSTEIN Keeping my focus on storm water issues, my biggest concern is that people change the way they view their water, and hopefully see it as a resource. to be protected. Things like rain barrels and rain gardens are important. Solutions are not just getting water off the land, into the storm drain and down to the river; but rather, seeing water as a resource to be used effectively.

We’’re seeing pretty good response in urban areas to such initiatives. Kansas City has its “10,000 Rain Gardens Initiative” as their goal. The focus of some of my work is to get that happening in places like Somerville which has a highly urbanized Peter’s Brook running through it – but the potential is there to educate and teach people how to use store water as a resource. It could make a huge difference.

NWNL Will keeping water in our yards or local areas solve downriver problems?

KEN KLIPSTEIN Well, we now are getting “flashy” flooding, since we now get smaller amounts of rainfall – but more flooding because water is getting piped everywhere and concentrated. Now we are using tap water to sprinkle our lawns. It really makes no sense. Either you’re on a well which could run dry – or using tap water coming from your town’s water supply that’s has been piped around long distances. But collecting your own rainwater in a barrel for watering your garden or your lawn, that’s a big change.

NWNL That would significantly improve water availability?

KEN KLIPSTEIN It will help. A new Water Supply Master Plan coming from the state is strongly focused on that demand side. We’re looking at how we’re now using our potable water supply, because we know there’ll be more demand for it. Plus, we are looking at the issue of recycled water. A few issues are:

–Should we stop using treated potable water to irrigate golf courses?

–In coastal areas, 1 billion gallons of wastewater are piped daily into the ocean, and thus lost to our freshwater system. Instead, what if those 1-billion gallons of water were put into what folks call the “purple pipe with the U-turns” – instead of being discharged into the ocean. Other states have done it. Florida and California are probably the leaders in this. That recycled water could irrigate golf courses, sod farms and other non-edible crops.

These potentially- important changes haven’t happened here yet, mainly because we’re considered a water-rich state. NJ gets close to 50” of rain per year. That’s plenty of water, especially when compared to San Diego CA which gets only 10” or less of rain. Other places get a mere 2”. That becomes especially critical in areas with developing communities.

NWNL Your point is that we have plenty of water; but are using it poorly?

KEN KLIPSTEIN Right, right.

JULIE ECKHERT Let’s talk in simpler terms. If water filters through the ground and then goes into the river, it’s naturally filtered. That means there’s no turbidity that would cost money to correct if used otherwise. But, what about water that just runs over the ground?

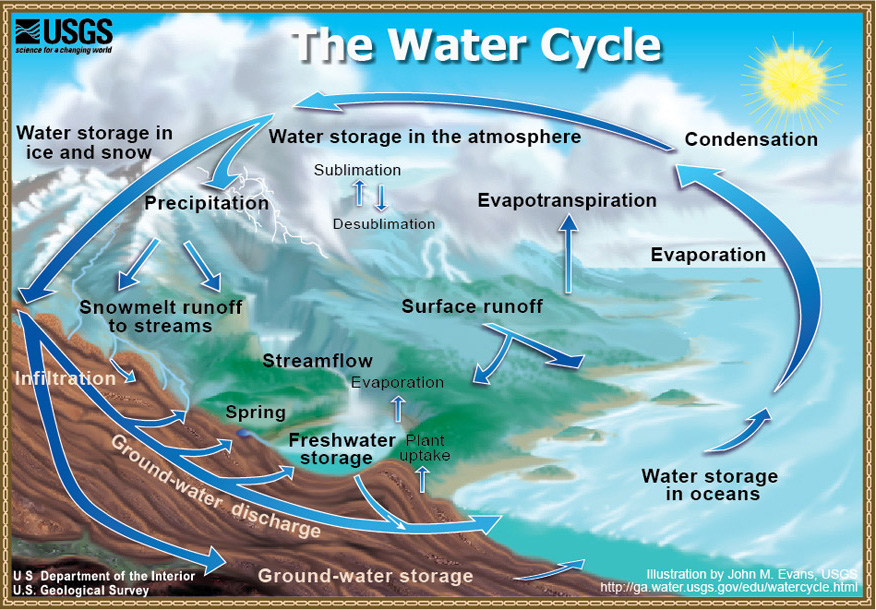

KEN KLIPSTEIN When we talk about the Hydrologic Cycle and impervious surfaces, we get into issues regarding groundwater exchange. The most critical thing about groundwater in our watershed systems is that in the summertime ground water is the base flow in our streams. That is a critical time for our systems.

I just mentioned we get an annual average of 50” of rain. In summer months, we get much less. Our streams then run on what filters through the ground and feeds into the stream as a base flow. That’s not rainwater – that is the base flow from our ground water system.

NWNL Regarding possible groundwater usage, would filtration be involved? Will it be okay to drink water that comes right out of the dirt?

KEN KLIPSTEIN The areas we protect for our urban water supply are largely ground water. New Jersey has rules in place that protect us from drinking contaminated groundwater. We require casing of wells and their separation from septic tanks because many who drink from their own wells also have a septic system that doesn’t get piped into a sewage treatment plant. So, there needs to be a healthy separation – and those standards are in place.

There are still farms in Hunterdon County with shallow dug wells. When they are less than 50’ deep, people end up drinking potentially high levels of bacteria from their farm run-off and other contaminated sources.

Many of those septic systems are not up to the standard that we’d like. We fixed many of those problems, as I mentioned this morning. We’ve come a long way in public health and in addressing gross contamination. Protections exist, but we need to maintain a healthy recharge rate for our streams. Those measures will allow our streams to filter and cleanse themselves.

NWNL Thanks, thanks so much, Ken – for this interview and for all you do for thirsty New Jersey residents.

Posted by NWNL on January 16, 2024.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.