Water – Crops – Wildlife

Kenya’s Amboseli-Kilimanjaro Ecosystem Spotlight

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Kenya’s Amboseli-Kilimanjaro Ecosystem Spotlight

Jeremy Goss

Big Life Foundation Communications Director

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Executive Director

Big Life Foundation

Water Needs

Permaculture

Crops

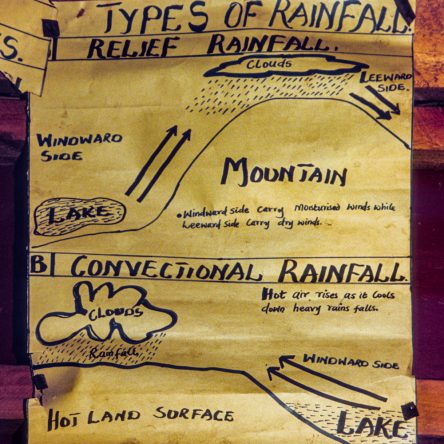

Climate Change / Rains & Snowmelt

Water Management

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.

About a year before this interview, Jeremy Goss left his South African home for Kenya’s Chyulu Hills – known as Hemingway’s “Green Hills of Africa” – to work for Big Life, then a 20-year-old conservation project. Big Life protects 1.6 million acres in the Amboseli-Kilimanjaro-Tsavo Ecosystem, using local Maasai rangers to protect crops, cattle and wildlife. Jeremy is working with the Maasai Group Ranch on introducing permaculture into this arid region with severe droughts that decimate Maasai cattle herds. Known for restoring streams, permaculture could be a win-win solution for the Maasai and their environment.

NWNL Jeremy, will you please “set the stage” by explaining what you do and where we are?

JEREMY GOSS I work for Big Life Foundation in Kenya’s Amboseli- Kilimanjaro Ecosystem. We work across the Maasai Group Ranches, from the lower slopes of Mt. Kilimanjaro across from Amboseli East to Tsavo National Park, including Chuylu National Park.

NWNL This interesting ecosystem seems to benefit from many underground springs supplied by Kilimanjaro’s runoff. But before we discuss that interesting water resource, tell us about Big Life Foundation and its Mission.

JEREMY GOSS Big Life works outside of the protected areas I just mentioned. We focus on a matrix between communities still largely living lifestyles that are compatible with wildlife conservation. We try to both incentivize them to preserve wildlife, on one end; and to provide a protective force by organizing community game scouts to protect wildlife.

NWNL What are your methods for accomplishing those two goals?

JEREMY GOSS We use a number of ways.

We’ve moved into a time in the world where local people aren’t going to look after iconic wildlife, just because they like seeing them around. Money’s their big issue now; and wild animals cost money. So, we’re trying to balance that cost with a number of benefits, whilst not making it a handout. We want to actually give people a reason to conserve wildlife, rather than just paying them to do it.

NWNL How does population growth and that encroachment figure into your work?

JEREMY GOSS That’s the biggest problem. People working with Big Life here have been addressing this issue for about 20 years and poaching [of the larger, more iconic wildlife] has now largely been brought under control. Yet, there’s still a fair amount of bush meat poaching [for local consumption]; and elephant poaching still goes on. Fortunately, we are supported by a network of game scouts and, especially, by community information we get all the time. As I say, once you have the support of the community, they are the ones who call the game scouts if they see anything suspicious or see a poacher.

We don’t only have 300 people employed. We’ve basically got the whole community on our side. With that, poaching has been brought largely under control. But now we have all these issues of wildlife conflict flaring, due to too much population pressure and animals running out of space. These ecosystems are so arid and so seasonal, that wildlife here traditionally needs big areas in which to move, as do livestock — cattle particularly.

Now people have started to settle here. Population pressures are increasing, and infrastructure is being built. A new tar road has made market access easier. Towns have sprung up, land tenure has changed, and so we have a very dynamic sociopolitical landscape as well. This really puts pressure on space. Population growth just compounds that.

NWNL Does Big Life promote any education in family planning?

JEREMY GOSS It’s a big problem here. I still am unsure whether traditionally there is a desire for Maasai to have big families. But big families are an indicator of wealth, just like having enough people to herd your cows proves to be the key to having a big family. I don’t know if it’s a lack of access to family planning or whether it’s a desire to not use family planning methods. That’s our next big challenge to take on here.

NWNL I’ve heard that family planning alone could reduce Kenya’s population growth by a third.

JEREMY GOSS I’d love it if that became successful here. We need to do the work and find out if people actually do want to reduce the size of their families. If so, then we can help them.

But if they don’t want to start reducing the numbers of children, we can try education, we can try to explain the consequences to people because it’s critical. However, and maybe it’s the pastoralist character in general, people here don’t think a long way ahead. Their problems are short term, and so people don’t often have the luxury of taking this kind of long-term view into account. I think a fair amount of education might help. But, at the end of the day, if people don’t want to reduce their family size, they’re not going to. So, it needs to start with them.

NWNL Regarding that pastoralist tendency to focus on the short-term, is it true that the Maasai do not have a word for future or a verb tense for future? If so, perhaps that reflects their approach to life which you just mentioned that, “Today is what counts and tomorrow – who knows?”

JEREMY GOSS I don’t know for sure, but it wouldn’t surprise me. They certainly don’t think about the future.

NWNL Today, we saw one of your game scouts walking along and talked to him about the lions. Could you describe a game scout’s typical day? I understand they walk very long distances.

JEREMY GOSS It’s a variable job. Our game scouts here are grouped in different units and have variable jobs. Within one, we have our dog unit. Those scouts spend a day training the dog in the morning, and then covering the area. In general, game scouts are based at remote outposts so that they can cover areas away from towns.

They wake up early in the morning. They patrol on foot and that distance varies. Usually, they patrol maybe 20 kilometers a day, responding to issues that arise as they go along. If they meet community members who say, “Hey, we heard about this,” or “We’ve had a problem here,” they might divert their route. Otherwise, they might just walk into an area that they haven’t covered in the last little period. That’s their basic assignment.

We also have specialized units. They have vehicle units for moving around and responding to issues. We have a good radio network, so if there are problems anywhere, the vehicle units get there quickly.

We have specialized units dealing with crop protection; and there are predator scouts. We have specialized people who deal with the livestock conflict. We have specialized people who deal with rhino protection. It’s quite variable, as I said; but the basic job is to wake up and get out there.

NWNL It’s interesting to me that the job of a game scout is so similar to the traditional life of a Maasai.

JEREMY GOSS Yes, very much so. And these guys can walk! I can’t keep up with them. Even though the scout wears a green uniform, his day has many similarities to the Maasai culture in which he’d be walking across the hills and plains – but wearing a red shuka. Traditionally they look after animals. whether cattle or wild animals; and they do it on foot. They are people who understand wild areas and wilderness. That’s what makes them so effective at helping Big Life meet its Mission.

NWNL Last night, you touched on your efforts to address the water issues and the Maasai’s effort to become farmers.

JEREMY GOSS Yes, the water issue is a big and growing issue here. Obviously, we’ve got fairly good water resources that flow off Kilimanjaro. I don’t know if anyone has detailed measurements, but we have reasonably well-stocked aquifers fed by Mount Kilimanjaro. Otherwise, most of the ecosystem is arid.

In 2008/2009 there was a big drought here. The figure I’ve heard says 70% of peoples’ livestock across the ecosystem died. For a lot of people, that meant everything. Left without capital to reinvest in a new herd, people had no options. So, they started resorting to farming because it’s cheaper to invest in. The land is here – and it is open. It was only a matter of getting some seeds in the ground. Thus, many people started farming out of necessity, but without any experience of farming methods or knowledge of how to do it.

JEREMY GOSS There are two ways that Maasai people farm here. One is people start farming themselves and doing it badly – with poor management of soil and horrendous water usage. They use flood irrigation for tomatoes in an arid landscape. That’s one of the most insane methods you can imagine. Other farmers are those who have come into the ecosystem from elsewhere. With this area’s communal land tenure, parts of some of these ranches have been not divided.

However, some Maasai have been given two-acre plots, and sometimes they’ll lease those plots to people from outside the ecosystem because they don’t have the farming experience. Sometimes, they’ll lease land to those within their tribe; and sometimes to other tribes, often the Wakamba or the Chagga from Tanzania. They will come in on a very short-term horizon with the sole purpose of extracting as much value as they can, since their deal is done on a profit-sharing basis.

These farmers will pump as many chemical fertilizers as they can into the soil, because they’re after a short-term benefit. They split profits with the Maasai landowner, who gets a great income for a few years and is very happy.

In some parts of the ecosystem, the farmers have already hit the point where their soil is no longer productive. Then they have to just abandon those farms completely. The farms are not big, but they will grow completely barren. They become arid soils that now can support nothing. We’ve seen a spread of this kind of farming and a lot of bad, bad farming practices, from water management through to excessive pesticide and fertilizer use.

[Editor’s Note: As of 2017, 70% of people in Africa relied on farming as their source of income, on land barely able to nourish crops. Satellite imagery of Africa revealed that more than 40 million Africans were farming on increasingly unproductive land.]

NWNL Farming in that area certainly necessitates irrigation. Where does that water come from?

JEREMY GOSS With our limited water resources, we have two types of water. We’ve got the stream flow which comes off Mt. Kilimanjaro. It is so heavily pumped that the water no longer gets all the way to downstream rivers that should flow down into Tsavo National Park. That really impacts the people further down those rivers who had relied on them for their own water and for water for their livestock

There is also upstream pumping of Kilimanjaro streams that impacts the local wildlife for three National Parks: Amboseli, Chyulu and Tsavo National Parks. So, yes, their wildlife – especially their renowned elephant herds – is being increasingly squeezed. That means the wildlife then has to enter human areas to find resources like water.

We are having increased conflicts around bore holes [drilled wells]. Pipes are being torn down, which creates more animosity amongst the community. All this comes from recent mismanagement of our ground water that comes from Mount Kilimanjaro.

NWNL What is your other water source?

JEREMY GOSS The other water we have is pipeline water, which is comes out of aquifers. It is pumped from Kilimanjaro-fed springs and is mostly used to supply settled areas further north. I don’t know if it gets as far as Nairobi, but it may do.

Now people are tapping those pipelines illegally, but the leadership of our ranchers is hesitant to stop them, because of the social issues involved. They’d quickly become quite unpopular if they told their people that they’re not allowed to farm anymore.

NWNL So, what happens to the elephant and other wildlife, as well as Maasai livestock and the Maasai themselves, if so much water is siphoned out of the pipes pumping water northwards from Mt. Kilimanjaro?

JEREMY GOSS We’re facing the threat of poor farming practices, and we have the spread of little Maasai farms, which means we will no longer have an extensive area where we can effectively keep elephants and thus protect the people and their crops. Those small farms also block wildlife movement corridors and make it harder for people – and us as game scouts – to protect these farming areas against wildlife raiding their crops. So, it’s quite a poisonous mix at the moment.

We are working more and more on wildlife/crop protection, because it’s a short-term solution. We try to keep the elephants out of Maasai farms to at least to demonstrate to the community that we want to help them.

The alternative is dead elephants. We’re now seeing many more elephants killed as a result of the conflict than from poaching. But long-term, we need to look at broader solutions. We’d like to see better zoning of this ecosystem. We could then intensify farming in certain areas, and could potentially fence it in, or have some other more effective methods of protecting those areas. That would help the Maasai in improving the farming methods.

JEREMY GOSS We’re trying to establish a permaculture plot at our headquarters, which we can then bring people to see. We’ve heard about permaculture, but we haven’t seen it in action. We’ve just started this, and it’s right in its infancy. If we can get a garden going, then we can feed our rangers and our scouts. If that works, we can start to bring the community to see that there’s an alternative.

NWNL I understand you’re still on a learning curve, but could you explain permaculture, as you see it?

JEREMY GOSS We’ve done a big amount of research into it. Two things attract me to permaculture. Firstly, it is a way to create better water capture and water retention in the soil through simple methods. Secondly, I had thought permaculture was a complicated new thing, so the first thing that I had to be taught was that it goes back to methods we previously used. People now have forgotten those methods, given all the modern so-called advancements. Those practices may work on big-scale farms; but for small farmers, they’re just not applicable.

So, permaculture re-introduces better methods of water retention and simple ways of achieving it. I also really like the idea of more diverse crops and planting species that complement each other. That can give each other the nutrients they need and minimize the risk of losing an entire crop if disease or pests come through.

JEREMY GOSS Through these safeguards, permaculture allows farmers to put food on their own table, as well as sell their crops. As we develop this, we are also trying to create markets for these products, so people can grow crops with higher value than the crops they are growing now. For instance, one of the big crops at the moment is tomatoes, which have a very high sale value. Therefore, that’s all they want to grow.

It’s quite difficult for us to tell them to change their one acre of high-value tomatoes, by replacing it with other crops which won’t get them as high a yield at market. But that will reinvigorate their soils. There will be some issues that we’re going to need to resolve, but it’s going to take time.

We want them to see there’s another way to farm – one which diversifies their product, doesn’t put all their eggs in one basket, and is less costly. But it’s a longer-term solution. We need to educate people and to say, “Listen, this is your land. That’s all you have. You need to look after it, and this is one way that you can reap some income from farming it, but you need to look after the land in the long term.”

That’s the hope. We want to intensify farming areas through better zoning, and better farming methods so people can count on surviving off these farms. That is important. Even though this is a crazy area to be farming, people rely on it; so, it’s going to stay.

NWNL Back to crops the Maasai growing here…. What crops have you introduced in addition to the high-value tomatoes?

JEREMY GOSS The main crop they now grow is maize, particularly up on the slopes of Kili, because there’s rain-fed agriculture there. I’m sorry that I didn’t mention that when I was talking about our water resources. Those maize farms have been on the slopes of Kilimanjaro for a long time. This isn’t the change.

The change is in these new farms spreading into new areas which historically didn’t have farming, and into some places that shouldn’t support farming. Maize has been their big crop and tomatoes are their big cash crop at the moment, because of the free water that people are either pumping out of the rivers or tapping off pipelines. People get a very big return on tomatoes, because there’s a big demand from Nairobi.

Their smaller crops include onions and some of leafy vegetables. We’d like to see more leafy vegetables planted, as there are growing markets for those. We haven’t looked too far into what the best crops are at the moment. Instead, we’re trying a mix of crops to see what works best in these environments.

Potentially, they’ll plant some of the various fruit trees. In permaculture, the desire is to grow crops with shade trees growing above to allow another crop and help with water retention. So, we hope to find some fruit trees that would do well in arid areas.

NWNL Are you are concerned about, or have you seen, decreases in rains increases in droughts, or decreases in glaciers on Kilimanjaro? Are local springs receiving less melt? Basically, these are climate change questions.

JEREMY GOSS Climate change…. I haven’t been here long enough to witness it. But I do know that the weather patterns have become less predictable here. There are seasons of severe rain and then severe drought. Weather patterns certainly seem to have become more variable, less predictable.

The glaciers on Kilimanjaro are melting. I don’t know the exact extents of ice that have been lost, but it’s quite well accepted that they are disappearing. Who knows when they’ll disappear completely? I’m also not sure how much of the water coming off Kilimanjaro is from those glaciers or how much difference that melt will make in the future.

There is a fair amount of snowmelt that comes off that feeds the rivers, but when will the glaciers eventually melt completely? And who knows what’s going to be left in these rivers? It’s certainly a problem that will increase in the future, particularly with people relying on water for their livestock and their crops.

The future will be very difficult, as people get squeezed into smaller and smaller areas that are less and less reliable in terms of resource production, whether it’s grass for their cattle or water for their crops.

NWNL What is the most important aspect to focus on regarding water issues?

JEREMY GOSS I think what’s become clear to me is that here water is where it all starts.

In this Amboseli-Mt Kilimanjaro Ecosystem, it’s the supply of water that dictates how this ecosystem operates. It’s quite complicated. As these water supplies change; as the pressures change; and the resources change; it becomes quite difficult to predict what’s going to happen.

I don’t think anyone really predicted an increase in farming after the last drought. With hindsight, it’s obvious; but I don’t think anyone predicted it at the time. As these climate events get worse, it’s very difficult to predict what will happen. That makes it hard for both managers and local people to plan for what’s going to happen. So, the more security we can provide with water management, the easier it is to plan for the future.

NWNL That is an insightful conclusion. Especially since, even before considering climate change impacts, returning degraded land to its original condition takes decades in arid and semi-arid parts of the world.

Good luck, and thank you so much for your time, Jeremy.

Posted by NWNL on June 27, 2021

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.