A Maasai Guide’s Conservation Views

Mara River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Mara River Basin

Wilson Naitoi

Wilderness Guide in Kenya’s Mara Conservancy

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Executive Director

Alison Fast

Barefoot Workshops, Videographer

2009

A School For Maasai Guides

Forests & Water

2015

The Value of The Mara River

Mara River Pollution

Mau Forest Headwaters

Deforestation – Irrigation – Climate Change

Awareness – Then Change

Charcoal Burning

Maasai Turn to Farming

Maasai & Wildlife

Safari Tourism

A Proposed Serengeti Highway

Elephants & Grasses & Termites

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.

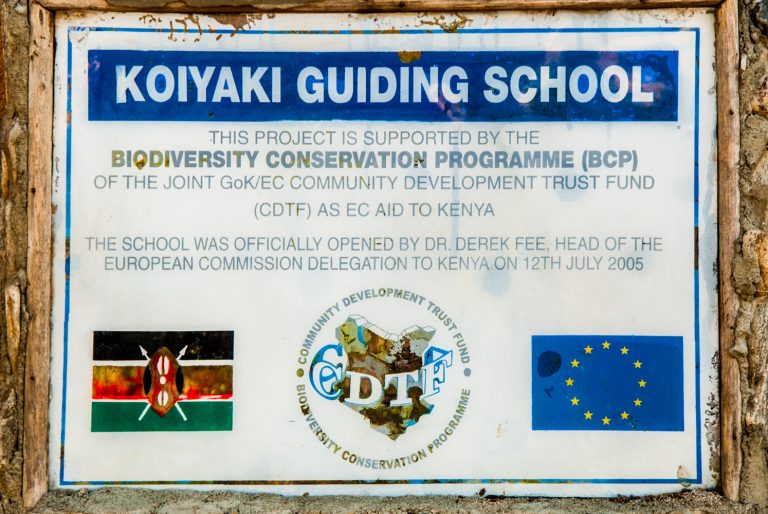

As a young Maasai, Wilson Naitoi was interested in wildlife and the environment his tribe has lived in for many millennia. He graduated in 2007 from Kenya’s recently established Koiyaki Wilderness Guiding School. Founded by the Beaton family and Maasai guides Jackson Looseyia and Dixon Kaelo, Koiyaki has depended on supportive donors. [In full disclosure, NWNL Director and Interviewer Alison Jones has covered tuition fees for this interviewee and one other earlier student.] Below are two separate interviews, six years apart, sharing Wilson’s ongoing observances as a conservatist and wilderness guide.

NWNL Hello, Wilson! It’s great to finally meet you after years of our email “Conversations on Conservation!” I’ve long waited for this chance to meet your family and discuss in person your training in conservation at Koiyaki Wilderness Guiding School – as well as your knowledge gained in your job as a guide in the Mara Conservancy.

WILSON NAITOI Yes! Koiyaki Wilderness Guiding School obviously benefitted me, because I’m working now at what I’ve wanted to do. So, I must pass a message to everyone about the importance of Koiyaki Guiding School.

My friends near home say I’m a friend to elephants because I work in the Mara Conservancy where there are many elephants and lions. This is where the Maasai community and the Mara Conservancy work together, although sometimes there is human-wildlife conflict.

NWNL At Koiyaki, you learned the details of conservation to keep habitats and rivers healthy. Do the Maasai here around your homestead also respect the Conservancy? Do they sense that it’s important to serve and maintain the ecosystem?

WILSON NAITOI The Mara Conservancy and organizations such as World Wildlife Fund/ WWF are trying to train people about the importance of habitats and today’s growing loss of habitats. Every Maasai has a portion of land, and the problem is that once they clear all their trees when they want to build, they need to buy trees from another person who cuts their trees. People really need to know about their conservation of the trees and rivers; and now they are beginning to know. This is a message going around to the Maasai communities.

WILSON NAITOI They have a very good, nearby example from the Kisii people who have no more indigenous forest. Everybody in Kisii territory has cleared their lands, and now you don’t see good trees there like here in Maasailand. The Maasai have maintained their natural forest, and never before needed to plant trees here. This is just natural forest.

So, the Maasai really know about forests. We are still spreading the message to them about the importance of habitats and habitat loss.

NWNL Do more children and more people create new conflicts now among the Maasai on whether to preserve the forest or whether to cut down more trees for more cattle?

WILSON NAITOI The chief of the Maasai community is telling his people not to cut the trees. They have must get a permit from the chief to cut their trees or clear their forest. Otherwise, the chiefs don’t allow it. That is the message to the Maasai nowadays. Even the government is trying to tell them about the importance of the habitats, and implications of the loss of their forests.

NWNL So, even the chief is telling the Maasai people?

WILSON NAITOI Yes. Plus, if WWF sees me, for instance, cutting trees around my home without permission of the chief, they will arrest me. We are trying to conserve this forest for the young generation. So now, people don’t clear the forest. WWF is telling them how important it is. The trees are just beautiful. They bring the rain, which is very good. You feel like you’re breathing very nicely when you are with trees.

Here we have wildlife, and those animals don’t get molested in the Maasai lands. But where there are no trees, there are no animals. So, the chief tells the Maasai not to cut the trees, because they are very important to the environment. If you cut all your trees, you’re going to lose because when you want to build your house, you need to buy trees from somewhere else, which is very expensive. So, the chief encourages them to plant more trees.

NWNL Thank you so much, Wilson, for all you do to help spread the chief’s word amongst your community.

NWNL Hello Wilson! It’s great to see you again. I’d like to chat about your connections with the Mara River. You grew up on the Isuria Escarpment above the Mara Conservancy and Mara River, and so you have always had access to the Mara River.

WILSON NAITOI Because I was born up on the escarpment, after my schooling at Koiyaki Wilderness Guiding School, I decided to become a wildlife guide in the Mara Conservancy. There, the Mara River is important. If we lose the Mara River, we lose all the animals – especially the Great Wildebeest Migration, which is one of the 7 Natural Wonders of the World. Thus the Mara is a very important river and we want to save it.

NWNL What concerns do you have regarding the Mara River? Is there enough water in the river? Is it clean enough?

WILSON NAITOI The problem facing the river is pollution, especially pollution from the many safari camps. Most of those camps are along the Mara River, so their sewage goes directly to the river. This pollution will kill the animals. They need to treat their sewage, so that by the time it gets into the river, it’s clean.

NWNL In 2007, I remember talking with Jackson Looseyia at Rekero Camp here in the Maasai Mara. He said Rekero Camp was building their own underground, sewage treatment center. He showed us where the camp’s effluent is filtered before going into the river. How many other camps in the Maasai Mara do you think are also treating their sewage now?

WILSON NAITOI Before, most of the camps let untreated sewage go direct to the river; but now the government, working with Kenya’s NEMA [National Environmental Management Authority], is making sure all the camps treat their sewage.

NWNL I understand another threat to the Mara River occurs at its source, the Mau Forest. There the government and people are cutting timber, often to create small farms that are locally called “shambas.” How was this allowed to happen?

WILSON NAITOI Well, thank God, the government now is protecting the Mau Forest, which protects our iconic animals, as well. But the Mau Forest is a political issue. Politicians have taken this land to give to their people, despite the Mau Forest Complex being an important water catchment area. As people cut trees and cultivate the land, it is not good at all.

Fortunately, the government is now moving people out of the forest and relocating them. It’s not confirmed where they take them, but they’ve moved their people out of the Mau Forest.

NWNL I hear this problem is becoming more political because people recently settled in the Mau Forest have come to consider it their home. And so now the government says, “We have a problem. Too many trees have been cut down. We have to reforest.”

Was there anger from the people about having to move away? Was there conflict over this?

WILSON NAITOI Oh, yes. There’s been a lot of anger especially from Indigenous Ogiek people, who say this has been their home since time immemorial. But the government claims the power to move them. There was a fight; but the government won. They moved the people and they’re planting trees, which is good.

NWNL You mentioned that the Mau Forest is a water catchment. Will you explain the role of a water catchment area is, and why it’s important?

WILSON NAITOI The water catchment provides all the water that comes into the Mara River. The Mau Forest is where the Mara River starts. So, if we cut all this forest, the river will become dry.

NWNL Have you been to the Mau Forest?

WILSON NAITOI I’ve been very close on the Nakuru side. Oh, my God, it’s a beautiful place. It needs to be conserved. I describe it as a paradise because it has beautiful trees. Very big trees, which is really good.

NWNL When you were at Koiyaki, did they teach you about the importance of forest and water catchment areas?

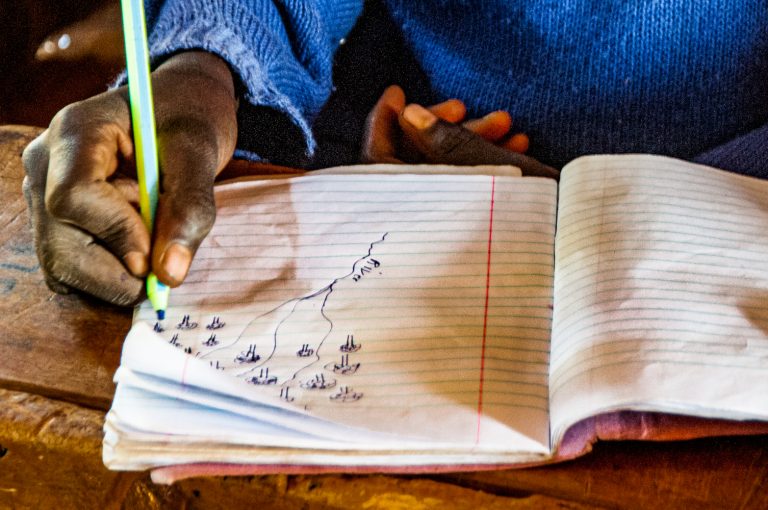

WILSON NAITOI I learned much about the environment when I went to Koiyaki Guiding School in 2006/2007, thanks to my sponsorship. While getting a certificate in guiding, we learned all the catchment areas, and why the government needs to protect them. I learned the importance of forest as a habitat for the animals and that, just as we need water, water is an important to the animals. No trees without water. No animals without water. Water is everything; so, we can’t destroy the catchment area.

NWNL What impacts do the wheat farms north of here have on the Mara River? Does that agriculture significantly reduce downstream water flows? Do you think these bigger wheat farms will take more water for irrigation?

WILSON NAITOI Yes, agriculture is a problem. North of the Mara, people have started irrigating their crops, which reduces the water from the Mara River. That needs to stop.

NWNL When I last saw you here in 2009, there was a terrible drought, and most of the cattle were dying. The Maasai were bringing their livestock up to the escarpment. It was the only place there was rain, and so all vegetation there had been eaten. Have you seen more droughts or floods since then? Perhaps you don’t see a difference in weather patterns, because you’re young – in your early 30’s. But do you hear older people worried about changes?

WILSON NAITOI I’m worried about the climate change. I’m still young, but not that young. When I was a young boy, I had to look after the cows and sheep. We would get a lot of rain – and I even remember a hailstorm. Now there’s a big difference – there is not as much rain as before. We have a lot more drought than before. I see a totally, big difference.

NWNL Are people in Kenya aware of these environmental problems we’ve talked about? Are school children learning about the importance of the forest, the impacts of climate change or the impacts of pollution? I believe that until people learn these things, nothing’s going to solve the problems.

WILSON NAITOI Oh, yes. In Kenya, people learn about agriculture, starting in our lowest primary schools, and then in secondary schools and college. So, people are aware.

The problem is that people don’t take action on these things. I remember early in my school, we learned about soil erosion and how to control it. “Don’t cut trees – Plant trees” and “If you cut one tree – Plant two.” That was taught early in Standard Class 3, when we learned about conservation and especially conserving the forest. So, people are now aware of conservation, especially in Kenya where the importance of forests is taught early.

NWNL That’s so important today. Then, once people are aware, what can individual Kenyans do? Is cattle herding changing among the Maasai? How do Maasai perceive their role in protecting the river?

WILSON NAITOI The Maasai now have changed their way of life. Some have become farmers planting crops. Some are still living the normal way they existed before, but from what I can see, there’s been a big change, because there’s not enough grass for the cows.

If you have more cows, you have no grass. So, during the drought, cows end up eating leaves from the trees. With no trees, there’s no grass. Then, everybody sees the importance of trees and the need to plant trees.

NWNL It seems that environmental awareness has reached down to the individual cattle owner.

WILSON NAITOI Yes.

NWNL Is the government in helping to teach and support people in how to be better about the environment? Or is this just a “grass roots” change, with individual farmers trying to change in order to protect the environment?

WILSON NAITOI Oh, yes, the government of Kenya is involved at the grass roots since you must get permission to cut trees. But people are difficult. Some people still sneak in to cut the trees for charcoal burning. But actually, if the government catches you cutting trees without special permission, you will be jailed. So, everybody knows not to cut trees.

NWNL Is there less charcoal burning now than ten years ago? Does that relate to whether there is more electricity available and more sustainable ways now of cooking and staying warm? And do you think those the solutions can end cutting trees to create charcoal?

WILSON NAITOI I think it’s a bigger problem now. When I grew up in Maasai-land, I never saw charcoal burned. But now, it’s much more common in the Maasai-land than before.

Yet, the Maasai don’t cut trees. It’s others who come in saying they want to farm and grow corn; so they are allowed to cut trees to prepare for the land. But they cut the trees to make charcoal, and then leave. That’s a new problem that the government needs to work on.

NWNL I’ve heard the Maasai are becoming farmers and some Maasai want to turn this whole Mara savanna wildlife habitat into farms for growing maize and wheat. They seem to think they’ll profit more from farming than from tourism.

WILSON NAITOI They’re crazy people. Changing the Mara into farms for growing maize is totally crazy. Yes, they can make profit; but where do you put our special animals? We love these animals! Where do they want them to go? Yes, people talk about that kind of scheme, but this actually is just crazy ideas.

As I told you, the Maasai are changing their way of life by becoming farmers. They cultivate corn and vegetables with other communities coming in to help, saying, “Your land is so big, let us help you.” If they start changing their way of life to farming, crops, they will do away with the animals because the elephants and zebra will come ruin your farm.

The answer is the government needs to provide compensation so we can see the way forward. This is a long-term problem and we need a lasting solution.

NWNL What value do the Maasai put on wildlife? On our game drive this morning, a safari guest from Turkey asked, “Do the Maasai eat lion? Do the Maasai eat these other animals we see out here, the impala?” Our driver Emanuel said, “No, the Maasai never have eaten game.” Can you respond by explaining the traditional Maasai appreciation of wildlife and living with the wildlife.

WILSON NAITOI The Maasai really value these animals. I was a young Maasai boy, I was told only stories of animals, nothing else. These people love these animals. They know how to avoid them and how to live with them. We are told, if you see a buffalo, climb a tree and keep a distance. If you see an elephant, go downwind. The Maasai know how to live with these animals and how to farm – and they will kill and eat these animals so their crops can grow.

Also, if you plant corn, you must wait three to six months to harvest it. So, what do they do? They go hunting while they wait for the maize to ripen. By the time it’s ready, they will have hunted as many as 14 animals. So, I raising cows and wildlife can work well with farming.

NWNL It seems part of the rise in bush-meat poaching is due to a lack of food right after planting?

WILSON NAITOI Yes, more bush meat has increased with farming. Since the Maasai are not good at farming, they get a friend from a different tribe unfortunately who will kill all animals on their land. If they see animals, they know it’s food. Maasai themselves actually don’t go hunting to kill a zebra or kill an impala, but somebody new who is training them to farm will kill an animal and say, “We have to kill this, or it will destroy your crop.” So, yes, there’s increased poaching with farming.

NWNL How do you assess the importance of tourism to protection of this ecosystem and the river? Will tourism provide more income than agriculture? If so, is the government promoting Kenyan tourism to the rest of the world? I’ve hearing the government could do more. Is tourism a key to saving this ecosystem?

WILSON NAITOI Yes, Maasai Mara tourists are important to sustainability of our wildlife and our national parks. More tourists bring more money to pay rangers and lodge staff and to help keep the ecosystem stable. But with no tourists, local people will eye the Mara for cattle grazing. They’ll want to cultivate this land for corn. So, we need the government to do more marketing right away for tourism in the Mara – for the sustainability of the Mara’s iconic wildlife.

NWNL I’ve noticed this week that tourists on game drives are from Turkey, Morocco, China, India and Iran. I’m the only American here, which is very different from when I came here in the 1980’s and 1990’s…

WILSON NAITOI It’s true.

NWNL Why do you think there’s been a drop in American tourists? Is that the government not reaching out to America anymore?

WILSON NAITOI I think the government is not in good terms with Americans, and there was a travel advisory. There was the issue of Ebola and political issues in Kenya. I think President Obama was unhappy with our President in some ways. Also, our President also was marketing tourism to China, but the Chinese are not there to sustain our ecosystem. They want to destroy it. Personally, I’d never seen the Chinese here before; but for the last two years, they’re flocking in for a month, a lot of Chinese. At the end of their visit, you hear these Chinese guys were caught with ivory at Mombasa Port or in Nairobi.

NWNL Are you aware of the Tanzanian government’s interest in building a highway across the northern Serengeti? If so, can you describe this possible project and its impacts?

WILSON NAITOI Yes, I’m aware. There has been a crazy idea to build a superhighway in Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park, which shares the same ecosystem and same wildlife with Kenya’s Maasai Mara. I have talked about this transboundary ecosystem, with its animals and the migration as a year-round phenomenon. It’s now February when animals are in the southern Serengeti. They will keep moving up to the western corridor, and then in May and June, they’ll start heading north. In July they’ll cross to the border, coming into Maasai Mara.

Close to the border is where they want to build this superhighway that would divide the Mara and the Serengeti, despite these animals moving north and south seasonally. Can you believe seeing such animals crossing the superhighway with all those cars and trucks – and all that number of animals? I think this is a crazy idea of the Tanzanian government because these animals will be killed. Then there’ll also be poaching. There’ll be accidents.

I don’t agree at all with this idea. It’s a totally crazy idea that needs to be stopped.

NWNL Let’s go back to why wildebeest come north every year to the Mara. It was this amazing rain-water-biodiversity story that led NWNL to choose this transboundary Mara River Basin as one of our case-study watersheds. The wildebeest come up for rain-fed grasses in the Mara, and then go back down to the Serengeti for grass after that’s grown back. They have their babies, and then return, bringing with them other animals. Zebras, lions and all the predators move with them.

WILSON NAITOI Yes, these animals are exhausted after coming north from the southern and the western corridors in search of water and grass. They come here because the Mara receives the highest rainfall – and if the Mara River is dry, there’s no water for them. So that is one more reason to conserve the Mau Forest as a water catchment area.

NWNL The Mara River crosses Kenya and Tanzania. Its waters flow into Lake Victoria and then up to the Mediterranean Sea via the Nile River. Do Kenya and Tanzania work together? Does Kenya have any influence on Tanzania to stop that highway?

WILSON NAITOI Both governments are friendly. Kenya and Tanzania are good-neighbor countries, and so I think they can discuss the idea of the superhighway. We have even the East Africa corporations working together.

NWNL Tanzania has an election coming up. Will this be a big issue in the election? What do you think they will do about this highway?

WILSON NAITOI I don’t know much about Tanzania politics; but they’re also conservationists. I think things will be better.

NWNL Let’s discuss why the elephant is important in this ecosystem, especially vis-à-vis water. I understand they dig the water holes for other species.

WILSON NAITOI The elephant is an amazing creature. I love elephants.

People say they destroy the environment. That’s a very wrong word to describe the elephant. We claim elephants are “environmental modifiers,” helping the tiny dik-dik and the impalas. They can reach the highest branches of trees, and bring them down for shorter browsers. And do you know the elephant process of wallowing in the mud? They dig and make water holes, which help when it rains. All animals will be drinking water there, instead of in the forest where they are ambushed by the lions. So, you can see the importance of an elephant as an “environmental modifier.”

NWNL I’ve never heard that term. I like it. What about the grasses here? It has very long roots, right?

WILSON NAITOI Yes, we have the red oat grass, an important grass. It’s very rich. The migration moves to the Mara because of the red oat grass; and they leave behind all their millions of dung piles to fertilize this ecosystem.

NWNL The grass’s long roots help store the water and thus prevent erosion, right? They seem to hold this ecosystem together by keeping enough water here.

WILSON NAITOI Yes, this is a natural balance, totally different from somebody cultivating this land after clearing this grass and the bushes. We need to sustain the Mara as is, not cultivate it.

NWNL What else, besides red oat grass and elephant water holes, helps hold water in this ecosystem? Do termites, ants or any other smaller species retain water, stop erosion or stop drought?

WILSON NAITOI Yes, termites in the Mara are also “environmental modifiers.” They build the huge “skyscrapers of the Mara,” as we call them. They are very important. The cheetah sit on the top of these very important termite mounds that hold water and make holes for other animals like snakes, the mongoose and the Nile monitor lizard. The trees also hold water.

NWNL Does that include the balanite trees. They’re disappearing. There seem to be no new ones. What’s happening to them?

WILSON NAITOI The elephants have come in. They have knocked down many of the balanites trees and eat the little ones coming up – the seedlings. I don’t see new young trees coming up. I worry that the Mara will lose all its trees. “Mara” is a Maasai word meaning spotted, because there were all these small clusters of trees dotting the plains. Now, there are not so many trees.

NWNL What do you think about the future of this plain?

WILSON NAITOI There’s a big change in climate – climate change. But new balanites are still growing and there are more animals than before. Some animals feed on leaves, like elephants and impalas. The elands and buffalo scratch with their big horns to break the branches, but still new ones come up, despite a lot of animals feeding on them.

NWNL If you go to Amboseli, which has many elephants and is dusty, dry and hotter than here, the only trees left are those in a fenced area.

WILSON NAITOI Some here were researching the balanites trees and put up a 2-meter cage where new balanites are coming up. By the time these small trees start growing, they shoot out of the cage and only those branches get cut off by an animal.

NWNL Wilson, thank you so much for your insights. I hope all your concerns can be met.

WILSON NAITOI I just want to say again that we, the Maasai, want to conserve water. Water is important. We want all stakeholders to get together —the government and friends— to talk about this issue. Let’s together conserve and protect this important catchment area and its source of water, because we can’t do without water.

NWNL Thank you, Wilson. I applaud your vision and your continuing efforts to protect the world’s unique Mara-Serengeti Ecosystem.

Posted by NWNL on August 9, 2021

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.