LNG Threatens the Columbia Estuary

Columbia River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Columbia River Basin

Cheryl Johnson Messing

Local Resident and School Librarian

Ted Messing

Local Resident, Fisherman

[Both Cheryl and Ted work with the Columbia Riverkeeper]

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director and Photographer

Bonnie Muench

Photographer, Artist & Book Designer

NWNL met with the Messings just after an expedition interview with residents of Columbia River’s Puget Island. Like those residents, Cheryl and Ted were intensely concerned over a proposed riverside terminal and associated pipelines to be built to accommodate foreign supplies of Liquified Natural Gas [LNG]. Their love of their watershed and knowledge of the value of the Estuary (where the Pacific Ocean meets the Columbia River) spawned their determination to research all implications of LNG accidents or leaks.

Fortunately they understood the need to join hands with other conservation groups in protecting their river, water resources, wetlands and home turf. Their success, as discussed below, is testimony to conservation including coordination and counselling with neighbors. Thus they saved the homes of their family, friends and millions of salmon.

STAKEHOLDERS’ LNG CONCERNS

FISHERIES are ESTUARY’S TOP VALUE

MITIGATION ISSUES

PROBLEMS in TRANSPORTING LNG

LNG ROUTE over LAND & WETLANDS

SIDE EFFECTS of LNG

GILLNET FISHING on the COLUMBIA

A LOST LEGACY

ASSESSING BRADWOOD LANDING

LOCAL & NATIONAL LNG PROTESTS

CITIZEN ACTIVISM & CONSERVATION

This whole ecosystem… is incredibly important for baby salmon,,,, This is their nursery where they grow to a certain size and age before they go out in the ocean for the next stage in their life cycle. – Ted Messing

[Wetlands] mitigation is a replacement attempt to compensate for the destruction LNG will bring. Failed has led us to where we are today, literally fighting over the last few salmon. – Ted Messing

Why I’m against LNG?… It’s non-renewable and imported.– Cheryl Messing

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

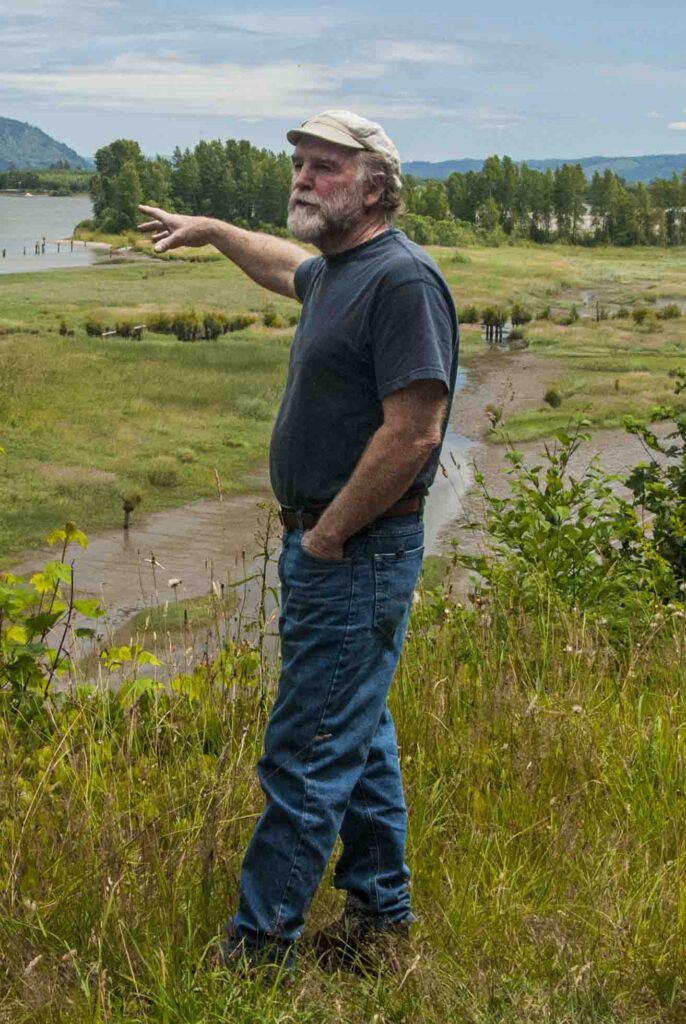

NWNL Cheryl and Ted, thank you for bringing us to this lovely site, sadly now downstream of a proposed site for a terminal for Liquified Natural Gas [hereafter, LNG]. We are now at old docks on the Clifton Channel that represent some of the Columbia River’s history, as well as today’s site for discussing your environmental concerns. Let’s start by discussing the background of your activism against the proposed LNG terminals.

TED MESSING I’m over a 30-year resident of Brownsmead, a few miles down the Clifton Channel. Cheryl and I are married and have raised two children here. In our early days, we used to camp on the river. We became passionate about the Columbia River and its health — particularly its salmon and salmon fishing.

CHERYL MESSING The Columbia River is now a part of a contemporary “gold rush” as we move into “peak oil.” There are now 4 potential proposals for the Columbia River. One proposal is close to the Columbia River Estuary, downriver from where we live. We learned about that from friends in Astoria who were involved. The second proposal, Bradwood Proposal, popped up just upriver behind us.

NWNL We can practically see that point from here, right?

CHERYL MESSING Yes, it’s very close to here, and to our neighborhood. When we heard about it, we joined others to educate ourselves, and then to educate our community on potential LNG impacts on the Columbia River.

NWNL So, you view the LNG issue from a stakeholder’s point of view?

CHERYL MESSING Yes. For 20 years I’ve worked for the Astoria school district as a library media specialist in its middle and elementary schools. We love the Columbia River. It is part of the history and culture of everybody who lives along this part of the river. We’re passionate about not letting bad things happen.

NWNL What are the values of this estuary for the general population of the Columbia River watershed?

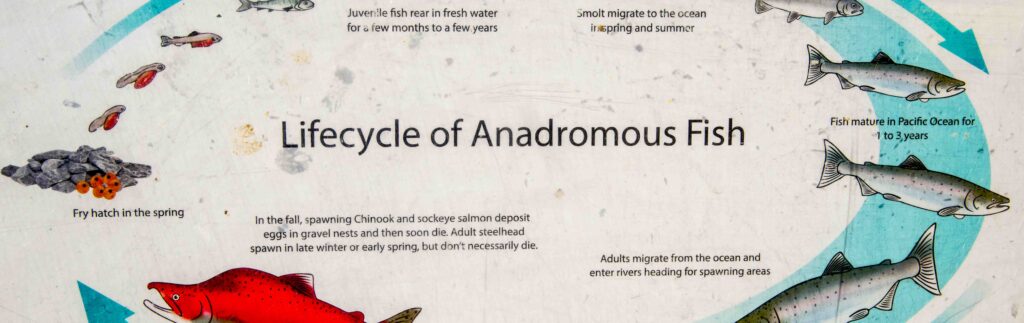

TED MESSING Primarily, this river’s value is in its fisheries. The Columbia River estuary is a salmon nursery, where baby salmon come downriver to grow before they head out to sea. These nurseries support every Columbia River Basin salmon run — whether in the Willamette River, Idaho rivers, and all tributaries still nurturing salmon runs. Then those baby salmon live in this estuary until they are ready to enter the ocean.

NWNL How long do they stay in this estuary?

TED MESSING Some stay up to two years. Each species of salmon spends a different amount of time in this estuary. The importance of this estuary to the life cycle of the salmon cannot be overstated. It’s critical because his stretch of the estuary is the last free-flowing, non-industrialized stretch of the Columbia River. Upriver, there are dams and industry. If you look at the river in Longview WA, you’ll see an industrial ditch, not a river. That’s probably the main reason we are opposed to LNG speculators coming here to sink an LNG tank farm in the middle of this Columbia River estuary. It is the grossest project possible to put into this river.

I used to be a commercial fisherman on the ocean on a “drag boat,” meaning we dragged for bottom fish. Thus, I’m familiar with the river’s fisheries. They are now my main concern.

The islands out here are wildlife refuges where people can now enjoy fishing, camping and picnicking. It’s an incredibly beautiful area. I just can’t even imagine the thought of sinking an LNG tank farm in the middle of this river.

CHERYL MESSING Not only are the baby salmon coming downriver, but adult salmon in the ocean travel upriver via this estuary to spawn. They return upstream to their homeland, to their original stream to spawn. Biologists tell us that the East Coast rivers are so polluted and degraded that their people are spending millions and millions of dollars to bring their rivers back to the healthy level that the Columbia meets today. Rather than trashing a river and then spending millions to bring it back, it makes much more sense to take care of the quality that we already have.

NWNL Would the proposed LNG terminals also affect white sturgeon and other native fish, as well as the salmon in this estuary?

TED MESSING Oh, absolutely, absolutely. I’ve just talked about salmon because I’m the most familiar with its life cycle. Certainly, other fish species use this estuary in various parts of their life cycles.

[Editor’s Note: Monterey Aquarium signage on steelhead cycles explains that: “Steelhead make a heroic odyssey to the sea and back: Each fall, steelhead return from the ocean to the coastal streams of their birth to lay and fertilize their eggs. Some young return to the sea, continuing the ancient cycle – often making the journey for several seasons.”]

CHERYL MESSING Currently 13 species of salmon and steelhead trout on the Columbia River are either threatened or endangered.

TED MESSING But today, we worry that an important fishery issue could be created by the LNG industry as well as the industries here. They say they can mitigate the problems. Mitigation is a replacement attempt to compensate for the destruction LNG will bring. And failed mitigation is what has led us to where we are today, literally fighting over the last few salmon. Failed mitigation has led us to where we are today.

NWNL How has mitigation failed? What industries have been required to mitigate for their impacts on the Columbia River?

TED MESSING Dams and industry must mitigate for their impacts. If an industry’s development will destroy “X” acres of wetlands, that industry will turn elsewhere to assist conservation efforts. For instance, they could buy an island that’s diked in; breach the dikes; flood the island and call that mitigation. They can claim, “We’ve destroyed 50 acres over here, but we’re going to give you 75 acres over there on that island.” But it doesn’t work that way. The estuary is better left alone, rather than attempting mitigation.

NWNL Can you describe how LNG would be brought here: the process and the impacts of a LNG terminal and pipeline to this reach of the Columbia River?

TED MESSING The life cycle of LNG begins when it comes out of the ground as natural gas from huge gas fields in Australia, Indonesia and the Middle East. They “super-cool” it to -260°. It condenses 600 times and turns to liquid. Then it is pumped onto a ship, serving as a giant Thermos bottle bringing the gas over to the US as a liquid. The gas comes ashore as a liquid into minus-260° large tanks, which are also like giant Thermos bottles. Then they warm it again to return it to natural gas.

At this point they can then distribute the gas via 36”, high-pressure pipelines. This gas is not odorized at this time; so if there are any leaks, we’ll never know it until it explodes.

NWNL Why wouldn’t they create a detectable odor that could serve as a warning sign?

TED MESSING Evidently, they’re not able to odorize it at the initial pipeline stage of transporting this gas. But I don’t have the technical answer on that.

NWNL Where does the energy come from to keep the gas in that subzero temperature? It must be enormous.

TED MESSING I’m pretty sure they burn mostly natural gas to warm the LNG and return it into a natural gas. LNG is not flammable in its minus-260° liquid state. But if there is any breach on a ship, in the liquid pipeline or in a tank, LNG will immediately start warming up and giving off natural gas. Once that ‘gas cloud” forms above the liquid, it has created a 15% mixture with the air and is ready “to go.” Any kind of spark, even a spark plug, will set it off. Once it starts burning, you cannot put out that fire because the pool of LNG beneath it feeds this fire.

So, that is the main hazard of LNG. The LNG industry touts that in their 40 years working with LNG, there’s never been an accident. But the word they leave off is “yet.” So, it’s only a matter of time. Any machine breaks down eventually..

CHERYL MESSING In that process of importing the LNG, they’ve put it on 900’-long tankers. They’re now building and proposing to use tankers that are 1,000-1200’ long. To serve the terminal closest to our home and the one just upriver from here, they’d bring the tankers upriver 38 miles and then offload the LNG to be cooled.

At that site, they’d need to dredge 55 acres of estuary wetlands for these tankers to turn around. dock and offload their LNG. It would irreversibly destroy 55 acres of prime salmon habitat in the Columbia River. As Ted mentioned, to fulfill mitigation requirements, they’d replace 55 acres of estuary elsewhere.

This estuary has evolved over thousands of years. The Columbia River and its salmon, an old species, figured out what worked and have thus survived all this time. So why we would arbitrarily take productive land out of production, and then arbitrarily put something else in a different place? It won’t work. That’s why salmon are in danger.

NWNL What happens after the gas comes into the Terminal? How would LNG be in the pipelines. Do these pipelines already exist, or will they have to be installed.? Where will they take the LNG?

TED MESSING After the LNG comes in on a “giant Thermos” ship, it’s pumped ashore in liquid form and maintained in minus-260° tanks, conditions under which it’s not explosive. LNG naturally wants to return to the ambient temperature in a gaseous state so, they re-gasify the LNG by warming it.

Regarding where they’ll pipe the LNG, there are several proposed routes via 36” pipelines to California. That’s the state with the greatest need for gas, so it will all go to California, which will pay the highest price.

NWNL I assume the pipeline is yet to be installed?

TED MESSING Correct. They’re not even 100% sure of the route. Basically, it will follow the Columbia River to Port Westward, probably 10 or 20 miles upriver. Then pipes will cross under the Columbia River, come up on the Washington side and go to the main north-south pipeline, parallel to Interstate 5.

But there’s another pipeline route, which is probably their #1 choice. This Palomar Pipeline will go over the mountains to Mist, Oregon, then straight to Madras to hook up with a north-south pipeline to California.

CHERYL MESSING For the storage tanks, they need to fill wetlands at Redwood at the southern end of the Oregon I-5 corridor. The pipelines need to cross streams and wetlands. So collectively, from beginning to end, this project will have huge impacts on the Columbia River Basin. They’ll dredge critical habitat right out of the river to bring the tankers in. They’ll fill in wetlands to build the tanks. The pipelines will cross wetlands and streams – causing an incredible impact on the Columbia Estuary and its wetlands.

NWNL So importing and delivering LNG impacts the estuary and its wetlands?

CHERYL MESSING Yes and in our ecosystems, everything is interdependent. The Columbia River Estuary is a spider web: if you pluck out one piece, it influences every other piece. Because salmon move upstream to spawn and downstream to live, every stream that feeds into the estuary is critical. Every wetland is critical. The whole thing is integrated. It’s all part of a whole.

NWNL Right. Regarding the pipelines, please explain the odor you mentioned.

TED MESSING When natural gas comes out of the ground or after it’s liquified with warming, it has no odor. However, they inject an odor in the natural gas in your house. It smells like rotten bananas so you immediately sense there’s a leak. However, gas in the LNG 36”-diameter, high-pressure pipeline has no odor. So, we won’t know if there’s a leak in the pipeline – or if the LNG ship breached causing the LNG to float across the water giving off natural gas the whole time. We’d would have no idea this natural gas was out until it exploded and then you would be burned up.

NWNL If the LNG facility is built here, will that bring in associated industries?

TED MESSING We think there’ll be a domino effect of this source of gas, this LNG facility. And it will bring in more gas than Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and the whole region combined could use. So, that’s why I say much of the LNG will go to where they can get the highest price — California.

CHERYL MESSING Right now, the Columbia River estuary is not industrialized. But LNG terminals would open the gate to industrialization such as we’ve never seen in this estuary. For the last 10 or 20 years, the city of Astoria, at the mouth of the Columbia River, has nicely promoted itself as a historical and cultural destination. Yet this kind of heavy industry is completely incompatible with that community and the direction it’s moving.

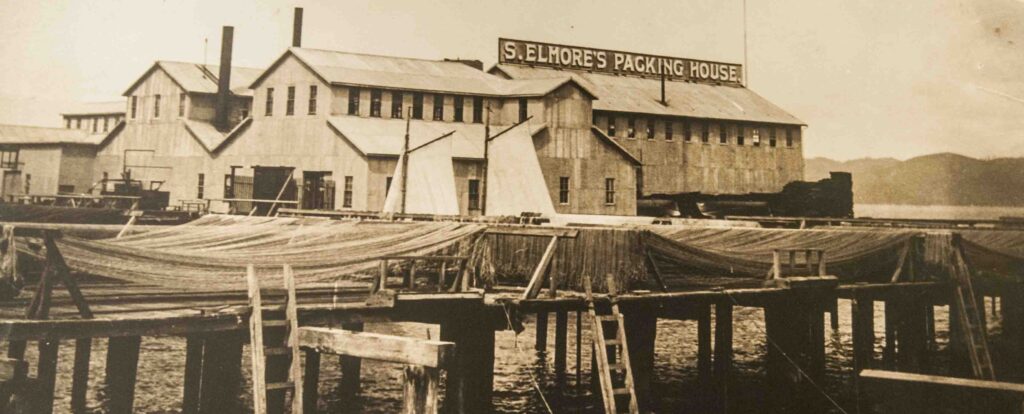

NWNL Speaking of community cultures, we’re sitting on an historical site right here. Ted, since you’re the fisherman, can you explain?

TED MESSING Well, this was once a booming fishing community of Clifton. I believe it was Italian and Greek fisherman who used it for over 100 years. They followed the salmon north but did their processing and canning here where they would fix boats, repair nets, dry nets. They spread their gillnets out in the shed behind so that they could dry and repair them. You can see some of the racks in here where the gillnet boats were tied up.

NWNL Could you explain gillnetting?

TED MESSING Today, gillnet fishermen string out a net, now made of monofilament line. In the early days, I’m sure it was linen or something like that. On the boat just down from me is a rolled-up gillnet.

Gillnetters have two lines. The top line goes across the net with floats every so often so the net floats on the surface. The bottom line has weights on it. So, this net hangs like a curtain in the current. As the salmon swim upstream, they don’t see the net until too late. They swim in and get caught because they can’t back out. The net catches the fish by their gills, hence the word gillnet.

Gillnetters fish on a certain tide. They’re very timed to the tides. When their net is full, they reel it in. In the old days, they literally pulled it in by hand and picked the fish out. They come to a fish in the net, pick it out, throw it in the cool box to keep it. Then they continue pulling in their net.

NWNL Do they still gillnet in this region of the estuary?

TED MESSING Yes, but it is very limited., often due to the small number of fish left. Sometimes they’re out for a few hours; or sometimes they’re out for a few days because, like I say, everyone is fighting over the last few fish.

TED MESSING We’re seeing an extremely sad legacy on the Columbia River today. This river has been so abused. The fish here were so plentiful. They talk about how you could literally walk across this river on the backs of the salmon; and that literally was true in the early days. Thirteen species of salmon are now threatened and endangered. Fishing these species is limited to a few hours, a few days. Recreational fishermen are fighting commercial gillnetters. Native Americans want their say. This river now is a very sad legacy we are leaving for our grandchildren. The saddest thing is what this river once was versus what it is today.

A run of fish called “the June Hogs” is a perfect example of man’s disregard for this river. This is the end of June, so these fish should be coming through here right now. They were huge, huge fish, hence the name “June Hogs.” These June Hogs traveled upstream, clear into Canada, to spawn in the headwaters of this river. But when they built the Grand Coulee Dam, they didn’t put in a fish ladder. So that species’ genetic pool is gone from this earth. It is gone – and that’s just one example of the legacy we’re leaving our grandchildren. I get sad when I think about it.

CHERYL MESSING The LNG would just add insult to that injury. There are many ways LNG terminals would affect the Columbia’s salmon. Ships would come upriver 3 times a week. They would need to take on ballast, so, they’d take water out of the Columbia River and then export it, lowering levels. The current amount of water in the Columbia River is critical for the fish – as is its temperature.

Also, as these ships suck up water for ballast, they could also suck up juvenile salmon. They only have proposals for screening the juveniles, but no plan that will work yet…. They just have several ideas for screening.

NWNL The screening would be for juveniles and adults?

CHERYL MESSING Correct. Having lost so many salmon already from this river, we don’t want to lose any more.

TED MESSING Yes, this spot overlooks Bradwood Landing, where one LNG terminal is proposed to be built. The geographic features of this area include the wetlands and waterway you see in the foreground. These few pilings mark the estuary of Hunt Creek Stream that flows into the Columbia River via the Clifton Channel right here. This is a Class One stream, with a steelhead run. The proximity of an LNG terminal would alter and, to a yet-unknown extent, endanger this estuary and its salmon.

Across from that line of trees is some light sand where the tank farm would be built. It would fill an old mill pond there, destroying 3.5 to 5 acres of wetlands. Where you see white sand, they’ll build 3 tanks with 250’ wide by 150’ high LNG tanks. They will hold LNG in liquid state until it is gasified. It’ll then be pumped into the pipeline to enter the grid.

At the entrance to Clifton Channel is open water on the left. There’s a shoal out there where water is only 10-20’ deep. That will become a 50+ acre hole, dredged 43’ deep. Then, their 900-1200’ tankers of LNG will come 38 miles upriver and be turned around by large tractor tugs to unload. A dock system will extend out in the river, disrupting and destroying this estuary. But this is an incredibly important estuary for baby salmon.

The entrance to Clifton Channel effectively will be cut off from any recreational or commercial fishers when an LNG ship is tied at that terminal, The ships will have 500-yard safety and security zones, enforced by Coast Guard gunboats. No one, going up or downriver, will be able to get in or out of this channel. So, these wetlands, this Hunt Creek Estuary, the mill pond and this important habitat for baby salmon will be altered, filled and destroyed. In short, this estuary will become industrialized.

NWNL You believe more industry will follow this plant?

TED MESSING Yes, it’s only logical. If you bring in massive quantities of gas – more than Oregon, Washington and Idaho can use – it only follows that other industries will come, seeking the use of that gas. We’re already facing the sad loss of our salmon legacy; but this would be another nail in the salmons’ coffin. That’s what this LNG terminal would mean.

See the “dolphin” out there? [That’s what we call three pilings tied together out in the river.] There’s an osprey nest there, right where they’ll build the terminal. They’ll destroy that nest.

NWNL Are those willows atop those pilings?

TED MESSING Yes. They grow there naturally. Today, these old pilings are an important part of the baby salmon’s habitat. They serve as protection for baby salmon, a place to hang out since the pilings protect them from predators. This whole ecosystem is gradually going back into its natural state, which is incredibly important for baby salmon. Especially as all the salmon runs in the Columbia River Basin use this estuary. This is their nursery where they grow to a certain size and age before they go out in the ocean for the next stage in their life cycle.

That island off in the distance with a few houses is Puget Island. The Estuary officially begins at the head of that island a mile or so up from here. There’s tidal influence right to the head of that island so, there is a tidal influence from the ocean here at Bradwood Landing. We are probably 5 miles from this point to the downstream mouth of the Columbia River. This is considered the Columbia River Estuary.

NWNL Cheryl, you said, “The Columbia River looks good today.” How do you think it will look in the future if there’s an LNG plant right behind us?

CHERYL MESSING It will be dramatically different. There will be:

NWNL So, what are you two doing to end this threat, besides wearing your buttons that say, “No LNG” and “Stop LNG”?

CHERYL MESSING A fine group of people passionate about the Columbia River have joined together from both Washington and Oregon sides of the river. Ted and I are part of a grassroots organization based in Astoria. Collectively we have educated ourselves for 2 years on what LNG means and what it would mean to bring LNG into the Columbia River. Now we are trying to educate others.

There are two grassroots organizations on the Washington side; and one on Puget Island, directly across the river from where the terminal would be built. The Puget Island citizens will be directly impacted if that goes in. Farther upriver in Long View, there’s a good citizen organization that came together because the pipeline will go through their backyards and through their community. So, citizens on both the Washington and the Oregon side all along the estuary have come together to stop LNG from coming into our community.

NWNL Are other concerned groups working with you – perhaps concerned tribal groups, scientists, people in the media or artists?

CHERYL MESSING We started out small, as citizen activists, literally working at the kitchen table on evenings and weekends to educate ourselves. Then, as we educated the neighbors, we all began to come together.

NWNL You are a librarian, so you must be good at research! Where do get your research?

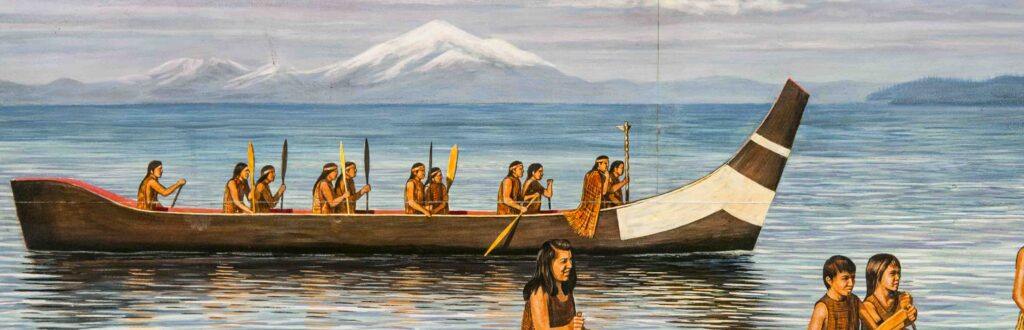

CHERYL MESSING Much of our research comes from the Internet; and we network. There are efforts to bring LNG terminals to many places across the United States, so there’s beginning to be a national network of opponents. We send information to places on the East Coast where LNG terminals are proposed, and they send information to us. Wildlife biologists are working with us. We are communicating with Tribes on the Columbia River with historical fishing rights that are very, very concerned about this.

We’re also working with national environmental organizations that are beginning to understand that this is not just a local issue or even just a regional issue. This is national issue in which they need to be involved and to work hand in hand with the local people.

NWNL We spoke with Jim Fisher who lives here in Clifton as a fisherman. His wife’s family has been here for generations. He asked us, “Where are the big national organizations? Why are they not here helping us?”

CHERYL MESSING Well, Washington and Oregon Audubon have recently come on board, as has Sierra Club for Oregon. However, those national organizations feel their plate is full; and indeed, they’re dealing with many issues all over the country. But again, this is not a local issue. It is a regional and national issue. We just hope they can spare some staff, sometime, to help us fight this.

NWNL In other words, this is not a NIMBY issue just about your backyard. The work you’re doing with other organizations around the country is evidence that it’s a bigger issue that impacts more than this Columbia River Estuary.

CHERYL MESSING For me, this is not a NIMBY issue. When people ask why I’m against LNG, I start with the big picture: LNG is non-renewable, and it’s imported. As a nation, we try hard to reduce our dependence on non-renewable imported energy. But LNG would just buy us 40 more years of importing fossil fuels. This doesn’t make any sense.

The Governor of Oregon recently has worked hard with the legislature to pass renewable-energy legislation, rather than bring in 40 more years of non-renewable imported energy. Right now, there are 4 proposals on the Columbia River to bring in LNG, with one farther south at Coos Bay. Some of our state legislators ask, “Well, if you don’t want it in your back yard, what about Coos Bay?” Collectively, as citizen activists, we have said “No. If LNG is not good for my neighborhood, it’s not good for your neighborhood.” It doesn’t belong anywhere in the Pacific Northwest.

NWNL What other forms of energy has the Oregon governor been touting?

CHERYL MESSING Oregon is beginning to invest in wind energy. I think, nationally, Oregon is the site of the largest wind energy forum. Of course, everybody now is looking at solar. The other exciting thing that’s happening in Oregon is they are beginning to investigate wave energy and tide energy. They are on the cutting edge. So I think investment in renewable energy is what makes sense for us as a state and as a nation.

CHERYL MESSING There is not much national conversation about conservation. For me, we as individuals in this nation need to talk very seriously about reducing our dependence on imported, non-renewable fossil energies.

NWNL Your focus is on cutting down on consumption? How do you suggest we do that?

CHERYL MESSING We live way out in the country, so getting to town is a big deal. Thus, to use less energy, we consolidate those trips until we have at least 5 errands. We share rides with neighbors. We have a little greenhouse for some passive solar heat at our house. We’re big into recycling. We don’t have curbside recycling; but we have baskets for green glass, tin, and aluminum that we truck into the town’s Recycle Center once a month. It’s not easy, but it’s important that we do it.

NWNL And getting back to our No Water, No Life efforts, what about water consumption. Are you are conserving water?

CHERYL MESSING Doing the best we can. We minimize showers, and laundry. Ted and I spent some time in South America where people don’t have clean water. When you see what we take for granted and how precious that water is for the rest of the world, then not letting the water run when you’re brushing your teeth, those simple things, and the small things become more important.

NWNL Statistics that say that water thoughtlessly wasted by Americans equates to the amount of water people elsewhere use in a whole day or a whole month.

CHERYL MESSING For me, the sweet part of doing the citizen activist is the chance to meet incredible people. Most of us working full time against LNG are neither independently wealthy nor retired. We have full time jobs. We have children. We are literally doing this at the kitchen table in the evenings and on the weekends. We use our money to print flyers to distribute. We use our time to make long distance phone calls to our legislators. But we have met incredible people through this process. Ted and I have made friendships that will continue for the rest of our life, whether the LNG comes or is defeated. There are wonderful, wonderful people on both the Columbia’s Washington and the Oregon side who have come together around this issue.

NWNL Have you made contacts with scientists, with scientific groups that are studying data on LNG, or fish biologists?

CHERYL MESSING As much as we can. The hard part again, being citizen activists, we don’t get paid to do any of this work. I’m neither a biologist nor an energy consultant. So, I rely on other people to share their research with us and then let us share it with the newspaper and use it in public testimony.

NWNL How do you access scientific data?

CHERYL MESSING Much is available through the Internet. When bigger environmental groups connect with scientists we have an entry to research in the field. But we need more.

The Columbia River is major U.S. river; but amazingly, not a lot of research has been done here. At one hearing this year, we learned that the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality [hereafter, DEQ] isn’t keeping records on air pollution here. We need more money invested in such things, so we have needed scientific evidence.

TED MESSING Regarding DEQ records, no one is doing accumulative monitoring of pollutions on the Oregon side of the whole river. No one.

NWNL Are you talking about water pollution or air pollution?

TED MESSING Everything combined! No one is keeping track.

CHERYL MESSING We work with the State and they’re contemplating issuing permits for this kind of industrial development on the Columbia River. They look at each development in isolation. They look at water and air pollution that would be contributed – but not at the “air-shed” nor the cumulative impacts on the watershed of the Columbia River Estuary. If, individually, each of the 4 LNG terminal sites meet the State’s criteria, then they okay them – but the State is not considering cumulative impacts.

NWNL Do you feel oversight needs more research or promotion?

CHERYL MESSING Hundreds of things need more research on our part.

NWNL Yes. But with more data, you could stand on much stronger legs. We’ve been up and down this river documenting communities and regions with no collected data. That leaves them legless. So, especially given your efforts, it seems reaching out for more science is critical.

CHERYL MESSING When you were on Puget Island did they talk about the salmon research done here? Jordan Kell had information about that.

NWNL In our interview they cited salmon-spawning populations that would be affected by the LNG.

CHERYL MESSING We’re eternally looking for the silver bullet — the one process or project or piece of information that would kill this project. A very knowledgeable friend in Astoria has worked on river issues and environmental issues for a long time. I asked him how best to get involved in this process as citizen activists. He explained, “Cheryl, there are 3 legs to this stool: educating the public, working on this politically, and working on this legally.

I responded, “Yes, but is there one “silver bullet?”

His answer was, “Cheryl, you must go in multiple directions, multiple times. We need people working together because we each have different talents. We each can make our own contribution. Each person can make a difference.”

NWNL Thank you both for sharing all that you are doing to make a difference.

Posted by NWNL on April 13, 2024.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.