Life on Grand Isle, LA

Mississippi River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Mississippi River Basin

Pat Landry

7th-generation Grand Isle resident

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director & Photographer

Gussie Baker

NWNL Expedition Guest

Family & Youth on Grand Isle

A Nature-Based Education

Assessing the Oil Industry

The BP Oil Spill

Oil Spills & Dispersants

Environmental Considerations

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.

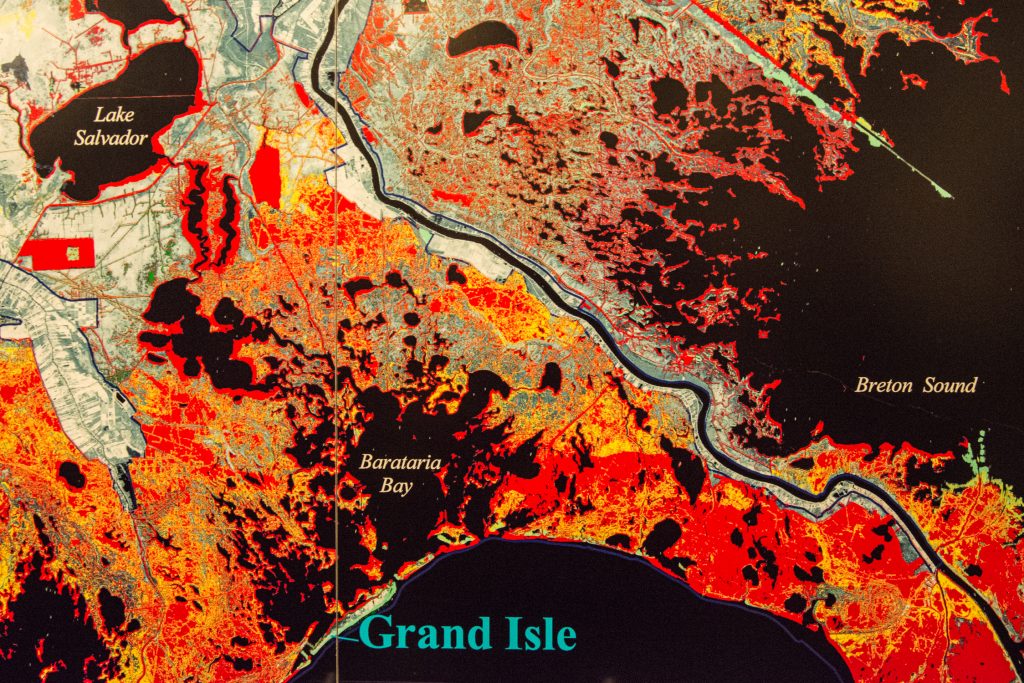

For many, Grand Isle is a camping, fishing or beach vacation destination at the southern end of LA Rte. 1. For NWNL, it was the final stop on its 1st Atchafalaya Basin Expedition. This tiny sliver of land breaks the Gulf’s waves before they enter the Barataria Bay. The south shore is a long stretch of sandy beach; the north shore faces the bay’s now-disappearing cypress swamps and marshes; and in between are oak forests enhanced by birding trails. As a 7th-generation resident, Pat shared with us his family’s life on Grand Isle and the island’s precarious future.

GUSSIE BAKER When we first arrived on Grand Isle, you told us to stop and listen. Thank you for that reminder. On this expedition, we’ve listened to Louisianans to learn about their lives and the values of their waterways. We’ve enjoyed learning from you and everybody we’ve had the pleasure of meeting.

So, let’s start with your family – did they come from France? Maybe directly, or via Nova Scotia like the Acadians?

PAT LANDRY Yes, the Landry side came from France. We have good records back to the 1800s. They wanted this climate. Having fished and farmed in France, Louisiana fit in with that. I learned French the same time I learned English, and I still don’t know English very well. My mom is from Lafitte. They were poorer and didn’t have very good records, so not too sure where all they came from.

My grandfather and my dad were oystermen by trade here. I’m the seventh generation here from the Landry family. This was my grandfather’s property, and this house was built for him. As an entrepreneur, he bought bank stocks and such. By trade, he cultivated and sold oysters. My dad followed, becoming an oysterman until he wore his back out. With 14 worn vertebrae, he had to sell out.

NWNL Growing up here, you must have enjoyed many local resources, including fish, shrimp, vegetables….

PAT LANDRY As a young boy, I helped the elderly gentleman next door who was a cucumber farmer. I picked his cucumbers at 25 cents a day, and he’d give us cucumbers. My great-grandfather was a cucumber farmer during the summer and fisherman during the winter – and sometimes both at the same time. So, I kinda knew about farming. My next job was following my grandfather as he caught mullet, crabs and fish with cast nets and then I’d carry them home. During school holidays, my dad made me go to the oyster camp to help out. That’s a hard, dirty job. He loved it. I hated it. When his back wore out, he wanted to turn the business over to me, but I didn’t want that.

NWNL What did you do after school years?

PAT LANDRY After high school, I worked for Texas A&M Research Foundation’s lab here on Grand Isle. My dad had worked for them off and on, since his oyster boat was a big lugger, perfect for their experiments. The oil industry had hired Texas A&M to run these experiments because a lot of the oystermen were blaming the oil industry for killing the oysters when their tugs and pipelines crossed their oyster beds. They found out that most of the mortality of the oysters was due to a disease called Dermocystidium marinum—they call it “dermo.” Dermo is prevalent in very warm, salty water, the best condition for oysters to grow in. But dermo doesn’t hurt humans if they eat an oyster that has it.

I worked for Texas A & M for 4 years and then went into the Army overseas. Afterwards, I went to work for the oil industry for 2 years. There was more money to be made in the oil industry than as fishermen. I learned about welders, roustabouts, and people working on rigs. Boy! they made up to $10,000 a year. Gee, that was more money than I could imagine I could spend.

So, I started doing that when a friend of my father in the Rotary Club asked me to work for Continental Oil Company, starting at $7.50 an hour. Back then, most people worked for $3.50 an hour. So, I worked my way up to senior production foreman, running transportation, materials, and making pretty good money. Plus, they had good insurance. I never had to borrow money.

I did a little bit of everything. I’ve painted, welded, and cut grass for a living. I bought tractors and so forth, which I still like to play with. I was able to put all my kids through college. To make extra money, I bought land from relatives and started a trailer park. Now, I own a trailer park, seven trailers and three homes. I’m relatively busy, and I enjoy it. All my life I’ve played with old cars, especially convertibles, motorcycles and fast boats. I also like to camp. So, I have no spare time at all and never get bored.

NWNL Are there other lessons you learned from older relatives?

PAT LANDRY Everybody would call my grandfather to know what to do. The French word traiteur means to us someone who treats problems. The hospital had many old women who were traiteurs, but no doctors. Back then, natural wisdom worked.

As a child, I was paralyzed one day. The doctor said there was nothing they could do. My grandfather cut a bunch of big old sirop feuilles. He put these syrup leaves in a bathtub of scalding hot water and then me. He did that two or three times. I then got up and walked; and am fine. I’ve never heard anybody mention that cure. For mouth sores, he’d peel, cut and soak flat-leaf cactus from his garden. The sores would go away a day after drinking it.

Sadly, I never asked my grandfather, where he learned all this. Maybe his grandparents? I don’t know how much schooling he had; but his handwriting was beautiful, and his record-keeping was immaculate. My dad too, even with just a 3rd or 4th grade education. He quit school early to work with his dad, but he was super-smart.

NWNL What a great life! Living here, do you see impacts on Grand Isle from the Mississippi River? Grand Isle is the very end of this river. Do you consciously feel that you are part of the great Mississippi River Basin?

PAT LANDRY Man has always thought he was a little smarter than Mother Nature; and so the biggest impact we’ve had here is that we levee-ed off the Mississippi River. The result is we don’t get any silt in these marshes. Grand Isle was built from silt that basically came from the river. Well, we don’t get that silt anymore. Now they want to get silt back here; but if you put too much fresh water in the marsh at one time, it kills all vegetation, oysters and fish. Mother Nature is a delicate balance, but Man has a hard time balancing that way.

NWNL You’ve given us a great summation of all we keep hearing. Is there any balance of interests between the oil industry and the fishermen?

PAT LANDRY Well, I’ve worked both sides. I trawled shrimp with my boat. Then I worked the oil industry, which was good in a lot of ways. It brought in a lot of work and income to people working on oil structures offshore: such as rigs to drill the well, or to put a platform and production equipment there to control the flow of the oil. (That’s called a “Christmas Tree.”) The legs of these platforms are great for fish, barnacles and all kinds of micro-organisms. It’s like an artificial reef. That has greatly helped the fishermen.

What destroyed our habitats are the canals dug in the marshes for inland oil rigs. The marsh is real shallow, so they’d dig channels through the marsh to get the rigs there. When the oil folks left, the government required them to dam the ends of these canals, which they did. But the fishermen would dig out these dams to use the canals to access different ports. Then, the current went through them and ate up the marsh. Had we known what we know now, we would have filled in these canals with soil and let the marsh repair itself.

NWNL Right. But what should we do now?

PAT LANDRY I think we need to go out and build levees in the marsh. On any high spot in the marsh, trees grow and slow the flow of water. So, when there’s a hurricane or something, that tree slows the influx of water and gives the marsh a chance to reclaim itself. Trees, birds and everything use the marsh. Ridges in the marsh would stop the current from running too strongly and washing away the marsh grasses and the nutrients that are in there.

When they dredged channels, the spoil was always put to the side. I think we need to use those spoils now to fill in low spots in the marsh so it can rebuild itself. Of course, it’s expensive. They tried to do it the cheapest way, but that damaged the environment. So, now we need to back up and make amends.

NWNL I must ask about the BP oil spill….

PAT LANDRY Well, it was a bad thing – very unfortunate. But I think Mother Nature will eventually correct everything better than man can. At the end of World War II, the German subs were torpedoing ships right off Grand Isle. As a young boy, I’d see the fires. We had tar balls and oil off our beaches for several years after that, and we lived with it. Eventually, Mother Nature took care of it. So, I think that can happen again.

We’ve learned that if we go into the marsh to take oil out, we trample that delicate marsh, and do more damage than if we left the oil there. Oil is biodegradable, so bacteria and such will eventually eat up the oil. A lot of clean-ups have helped greatly, and many people have made a lot of money from BP. Some deserved it, some didn’t.

It’ll be all right in the long run if we give Mother Nature enough time. If tar balls or oil show up from to time, we’ll clean up what we can get without trampling the marsh or hurting our environment. So far, the state has been testing all our seafood, and it’s ok. I eat oysters, fish, shrimp and anything caught over here. I’m 73 and I’m not dead yet.

NWNL When you say, “caught over here,” are you differentiating fish and shellfish from Grand Isle versus the rest of Louisiana?

PAT LANDRY Yes, because we were the area worst impacted by the spill, since it was offshore of us. As you go farther inland, the impact is less and less. Adjoining states, like Mississippi and Florida, were impacted a lot less than we were. We took it head-on, over here. From my boat, I saw areas where oil was very thick, very heavy and could only be cleaned up with oil mops and pumps. It still shows up from time to time.

NWNL If you put aside the BP spill, do you think shrimp, fish, or crawfish off Grand Isle is cleaner or healthier than that in the Basin?

PAT LANDRY Yes. I think our seafood here is better than in places further inland, since we don’t have big sewer systems or runoff into the water here. Most of Grand Isle has cesspools or septic tanks in the ground; and its sandy soil absorbs it well. Farther inland, big plants and sewage systems dump their waste right into the water. Here our biggest problem is drinking water quality, more than pollution effects on our seafood.

NWNL How do you feel about the quality of your drinking water?

PAT LANDRY Our drinking water now comes from New Orleans. We ran a pipeline all the way up to Lafitte, which gets its water from the west bank of New Orleans. For our first water system, we tapped off the water system of Lafourche Parish, near the Lockport area.

There were times when water levels were so low that salt water would meander up to Lafourche, and the water plant had a hard time producing enough water because the salt content was so high. That was another problem for us, because little current comes down by Lafourche, and we dammed up the bayou in northern Lafourche Parish. Now they’re trying to let a little bit more water come through to flush it out.

GUSSIE BAKER New Orleans water is not supposed to be great either.

PAT LANDRY No, but it doesn’t need as many chemicals to purify it. But it’s bad if you go north of Lake Pontchartrain, not because of the chemicals, but because it is well water and has a that “rotten egg” taste to it.

NWNL Are you facing issues of sea level rise or salt-water intrusion?

PAT LANDRY There is no salt-water intrusion on Grand Isle because we’re surrounded by salt water. But when they dug the ship channel from Grand Isle all the way to Lafitte, it seemed a big boon to water transportation. But that ship channel also gave the Gulf’s salt water a straight track inland all the way up to Lafitte. Cypress trees that were there are all dead now because of the salt-water intrusion.

In many other places, these oil industry canals, instead of slowing the marshes as a speedboat does, slowed fresh water down coming to us, and slowed saltwater going upstream to us. Now the marsh is basically gone in most of the areas here. Salt water just speeds into the marsh. And there’s nothing to slow the speed of freshwater as it comes down like that big blotter effect that the marsh had.

NWNL Two climate change questions. Do you see any sign of a rise in sea level? And do you think there is a greater intensity of storms these days? Are you concerned about these issues?

PAT LANDRY Yes, I believe sea level is rising. But my opinion of what’s happening is a little different than what I hear on TV. Everybody says, “Oh, the ice cap is melting,” and so forth. What they don’t mention is that half of the state is leveed off. All of Bayou Lafourche is leveed off. All these communities have levees around them. They pump the water out.

Water has nowhere to go anymore, and so all the silt that used to build land is going out over the Continental Shelf – filling up the bottom of the pot. So, the water has to come up. It must go somewhere. Our marsh areas that we had here were high land at one time. Here on the back of Grand Isle there used to be five-and-a-half feet of water and a lot of marsh. Now the marsh is disappearing. All these storms have washed the marsh into the deeper parts; and now I only have two-and-a-half feet of water.

So, water levels just keep on raising — because we’re filling in all the deep spots.

NWNL And intensity of storms?

PAT LANDRY The intensity of storms is getting worse. Like I say, El Nino is changing its pattern. Our tidal waves are rougher because the water levels are higher, and because we don’t have the marsh to slow the currents and the water down. Before Katrina, normally when we had a storm and north wind, we were in good shape here. We would have low tides, because it blew the water out. But Katrina was huge. So, due to the lack of marsh, it took the water all the way from Lafitte and pushed it to us. I had two-and-a-half feet of water where we’re sitting right now inside my house. I never had that happen before.

So, the storms are getting bigger. At one time, a little storm that would affect either Mississippi, Florida or Louisiana wouldn’t affect another area. Now we have these storms that affect anywhere from three to five states – encompassing the whole Gulf at one time. We never used to have that back when I was a young boy.

NWNL Back to the BP oil spill and the dispersants used in the clean-up. Are you concerned that remedy was unhealthy for the people who were putting them out there and people nearby.

PAT LANDRY Well, having been in the oil industry, I’ve had experience with dispersants. They’ve been used for years. Our biggest BP spill problem is that it was used in such large quantities. I don’t think we have experience or knowledge about this big a quantity.

So far, I don’t think it was as bad as some people thought it was. Some people may have really gotten sick, depending on their mental and physical health. I think a lot of people got sick because they could get money from it. Some people were very honest; some were not. But all in all, with all the tests and everything they’re getting right now, it’s not proving to be disastrous to us or our seafood, unless you were right in the dispersant in the concentrated areas.

I think we have a lot to learn from this. We just don’t know at this point what’s going to happen, given the amounts that were put in the Gulf. They’re saying there are places way out deep in the Gulf where patches of this dispersant are like underwater clouds. This may go away, and it may not. I don’t think we know. I think it’s kind of a wait-and-see situation.

NWNL Going back to your comment about all issues being a “balance,” do you think, on balance, that it’s good the oil industry has landed in Louisiana? Has it been a boon to Louisiana overall? In the balance of it, how would you weigh the pro’s and con’s?

PAT LANDRY I think the oil industry has been very good for Louisiana. It’s helped build schools and libraries and helped people’s standard of living. It’s helped build our roads. And it has helped the whole nation.

Without the oil that Louisiana produces, the US would have to import a lot more oil from foreign countries, which is detrimental to the whole country. We could have done some things a whole lot better; but, again, experience is the best teacher for all of us. The one thing I like is that people are now becoming aware of what we’ve done right and what we’ve done wrong. Hopefully we’ll correct the wrong things we’ve done.

NWNL What will help lead oil companies to accept responsibility for their damage?

PAT LANDRY People are becoming aware of our environment. At one time, the marsh was just thought of as wasteland. Nobody realized the importance of the marsh or our marine habitats. Now people are beginning to say, “Well, this is very valuable.”

Whenever we talked about saving Grand Isle, Grand Terre and Fourchon Beach, the reaction was, “Oh, we can’t do that. It’s going to wash away anyway. Don’t worry about it.” Well, they’re finding out now that if these barrier islands go, New Orleans, Baton Route, and all this region is going to be under water and will erode the levees around New Orleans. God knows where the shoreline would be then. So, we are the barrier. If we don’t take care of the Gulf’s barriers, all of Louisiana and the southern states will be in serious trouble.

NWNL You say, “We’ve done some things right and some things wrong; and “We’ve learned.” But, specifically, what has the oil industry done right, done wrong, or need to be change?

PAT LANDRY What I know about the oil industry is what I learned when I was working with Continental Oil. On Grand Isle they bulkheaded the shorelines along Bayou Rego to keep it from eroding away. They filled in behind it and made it into useful property with good drainage. What is now good land would have washed away. They are learning; and they’ve got the environmentalists working for them now.

If private industry doesn’t help out by bulkheading and reinforcing our shorelines, before long our shoreline is going to move inland. The oil industry has shored up much that would have washed away. Sometimes, they dug places where they shouldn’t have; but all in all, people have learned a lot from the oil industry as to what to do about the effects of oil. When I worked for Texas A&M, a lot of people were afraid of oil and afraid to touch oil. Oil is a natural resource. You can fill a tub with oil, sit in it, wash, and take a bath. You’re not going to be hurt – unless it’s that oil with poisonous gas.

We must realize oil is not our enemy, as some people think. Many still say, “Well, we’ve got to shut them down.” They don’t realize we all use oil. In response, they then say, “Well, go get electrical bike.” We’ve got to remember that all our plastic is made from oil. If you don’t grease your bike’s hubs or bearings, you won’t go very far. In some way or the other, almost everything we have now involves using a petroleum product – even medicines and pharmaceuticals now. Oil is very important. We learned a lot as we’ve produced it, but we need to learn to use it safely and economically.

NWNL You make a persuasive argument.

PAT LANDRY I’m so glad you came down. It’s people like you that come down here who can enlighten us and make us realize things that we didn’t know. Sometimes we live here in our own little world, and it takes outside people to explain what we don’t know, what we don’t appreciate, and make us a little bit wiser than we were before.

NWNL Thank you, Pat. And thank you for joining me in being a forever learner, open to trying to understand issues from all sides. Pat, being from a French family, you certainly understand the phrase, “Laissez les bons temps rouler!”

Ah! That was the smile I wanted. I asked that because I wanted you to smile for a photograph!

Pat Landry keeps his spirits up as he assesses the future

Posted by NWNL on September 12, 2021

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

Interview Guidelines describe the NWNL protocol for editing raw transcripts.

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.