The Chinook & William Clark Family

Columbia River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Columbia River Basin

Ray Gardner

Chief of the Chinook Nation

David Samansky

National Park Service Unit of Dismal Nitch

Jim Sayce

Washington State Historical Society

Peggy Disney

Chinook Member and basket weaver

The story of the Lower Columbia has always been centered on water – and cedar. After our 2007 “Source to Sea” Columbia River Expedition, NWNL joined the family of William Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame) as they “righted an old wrong.” Anxious to return east after 115 rainy, winter days, Clark stole a sea-going, high-bow/high-stern canoe from the Chinook on March 21, 1806, the eve of his return to the East. Seven generations later, the Clark family gifted Klmin, a new, but traditional, sea-going canoe, to the Chinook Nation. Below are some of the accounts shared with the Clark Family and guests.

RAY GARDNER: THE CHINOOK CREATION STORY

RAY GARDNER: CHINOOK CANOES

DAVID SAMANSKY & JIM SAYCE: AT DISMAL NITCH

JIM SAYCE: LOGGING & WEATHER

RAY GARDNER & PEGGY DISNEY: THE VALUE OF CEDAR

All images © Alison M Jones. All rights reserved.

This is Middle Village, a place where our ancestors fished, where we lived and what Lewis and Clark referred to as Station Camp. We have been here for tens of thousands of years; Lewis and Clark were here for 10 days – and in this general area for 127 days.

The campsite park we visited started out as “Lewis and Clark Campsite Park.” We really felt that that was not appropriate given the length of time we were here, 10,000 years versus the 10 days Lewis and Clark were here. This will be the first park ever built in the United States that will tell the entire story of the homeland tribe.

We’re very pleased with that. It is a way we can honor our ancestors and make sure their stories will go on forever. For us, this is a place rich in tradition, very near and dear to all of us and a place I call home. This God’s country – one of the most beautiful places in the United States. Our Turtle Island was referred to historically before this was North America!

I’m always very proud to give my lineage. My mother’s maiden name was Lois Robinson; her mother was Dora D. Clark; her mother was Annie Hawks; her mother and father were Nellie Secena and John Hawks. John’s father was Tom Hawks, whose proper given name was Huckswelt.

Huckswelt was the last chief of the Willapa Tribe, signer of the Tansy Point Treaties of 1851. That lineage–being a descendent of a chief and the elected chairman of the five tribes that comprise the nation–allows me the honor to be able to be here and speak to people about our land.

If you ever get into one of our canoes and call it a boat, we will get to see if you can walk on water — and it’s deep out there! They are canoes. Our canoes are living members of the tribe. They are a part of us, and of everything that we are. They’re how we travel. They’re how we traded. When we used these canoes, we left the mouth of this river and traveled north to what would now be Southern Alaska, and south to Central California. That was how far we went to trade with our canoes. So, our canoes are very well traveled. We went east up this river up to Celilo Falls which was the first major east-west trading hub.

Our canoes have a heart. You’ll see where that heart is tomorrow during the ceremony. Once our canoes are cleansed, blessed and given their name, they become a member of the tribe and are to be treated with that respect. One of the other thing to add: no negative feelings are allowed in the canoes. You must have pure, good thoughts, because we rely on those canoes to bring us home safe. If we bring negative thoughts into those canoes, we put our lives in peril. We’ve been out in waves that most of you would not go out to in a 40-50’ boat. Yet those canoes have always brought us home safe. They’re extremely capable vessels. There are 10,000 years of engineering that went into those canoes to make them what they are today. It’s remarkable what they can do.

Just to let you know – in times when we’ve had people in a canoe and they have started getting negative, we pull over and ask them to get out. It’s so important for me to keep my canoe pure, because I spend a lot of time out in this river, other rivers and other bodies of water. I know that my family always wants to be sure that I come home safely.

Not to offend anyone, but when we first found Lewis and Clark, we really felt they were pretty pathetic. They had these things that they called “canoes” but they were just really hollowed-out logs. They couldn’t keep them upright. The men were huddled up, their clothes were rotting off their backs, they were hungry, they were diseased. You can put it in perspective when you look at the fact that in 1792 Gray first came into this river in the Columbia Rediviva and the Lady Washington. By 1805, we’d been trading with the outside world for a long time. We’re well versed in all of this. So, the amount of trade items Lewis and Clark had left when they got here were nothing to us. They really didn’t even have anything that was worth our time to trade.

We traversed this river all the time. Our people lived on both sides and our canoes got us from point A to point B. It didn’t matter what the conditions were, our canoes were seaworthy enough. We were good enough canoe people that we just went. If we were going to go upriver, we waited for the incoming tides. If we wanted to come down the river, we waited for an outgoing tide. If it was too rough, there was nothing over there important enough for us to go, so we waited for another day. So you can imagine the jokes that we had around our campfires and after watching these folks in these funny looking logs.

National Park Service Unit of Dismal Nitch, Eagle Cliff & fresh water

DAVID SAMANSKY This summer we worked on a short film called, “In Search of Dismal Nitch” and found that Dismal Nitch isn’t in the place that we thought. This is the first place where the Lewis and Clark Expedition is distinctly uncomfortable and out of its element. I think for most of their way across the country, having spent most of their time in service east of the Mississippi, they had woodland skills that benefited them well.

Here they reached a place where everything is based around the water. Despite the fact they’d traveled 3,000 miles by water, here they met a culture unlike any they had seen along the way. The people here were comfortably at ease with both the stormy and the sometimes violent Columbia estuary, and with trade and other parts of European culture.

I think Lewis and Clark were used to being sort of a spectacle and using that to their advantage when they went through other villages. Here it wasn’t the case. The six days that they spent here were probably the most dangerous six days that they spent during the expedition. It was quite a frightening time. I think it was also frustrating [for Lewis and Clark] that the Chinookian canoes were arriving and going during weather that they had a hard time navigating through.

I think it was an uncomfortable time. They were never out of sight of a village when they were on the Lower Columbia; and they hadn’t seen as dense a population of people as ours. I think that their big question was, “Well, how are we going to interact with these people, especially since by the time we got here, we didn’t even have enough trade goods to buy things that are essential.”

JIM SAYCE Welcome! To get your bearings before we discuss canoes, the high rocks to my left are called Eagle Cliff. From there to where the boat and barge are parked is called Hungry Harbor.

The most important thing in terms of the Expedition’s use of the word Nitch, is that it means a small embankment, a small bay, also a small alcove. When Clark refers to Dismal Nitch, he refers to one embankment where they arrived 10th of November, 1805. They made two attempts to go around today’s Point Ellis, also called Point Distress. They didn’t make it because of the type of wind here.

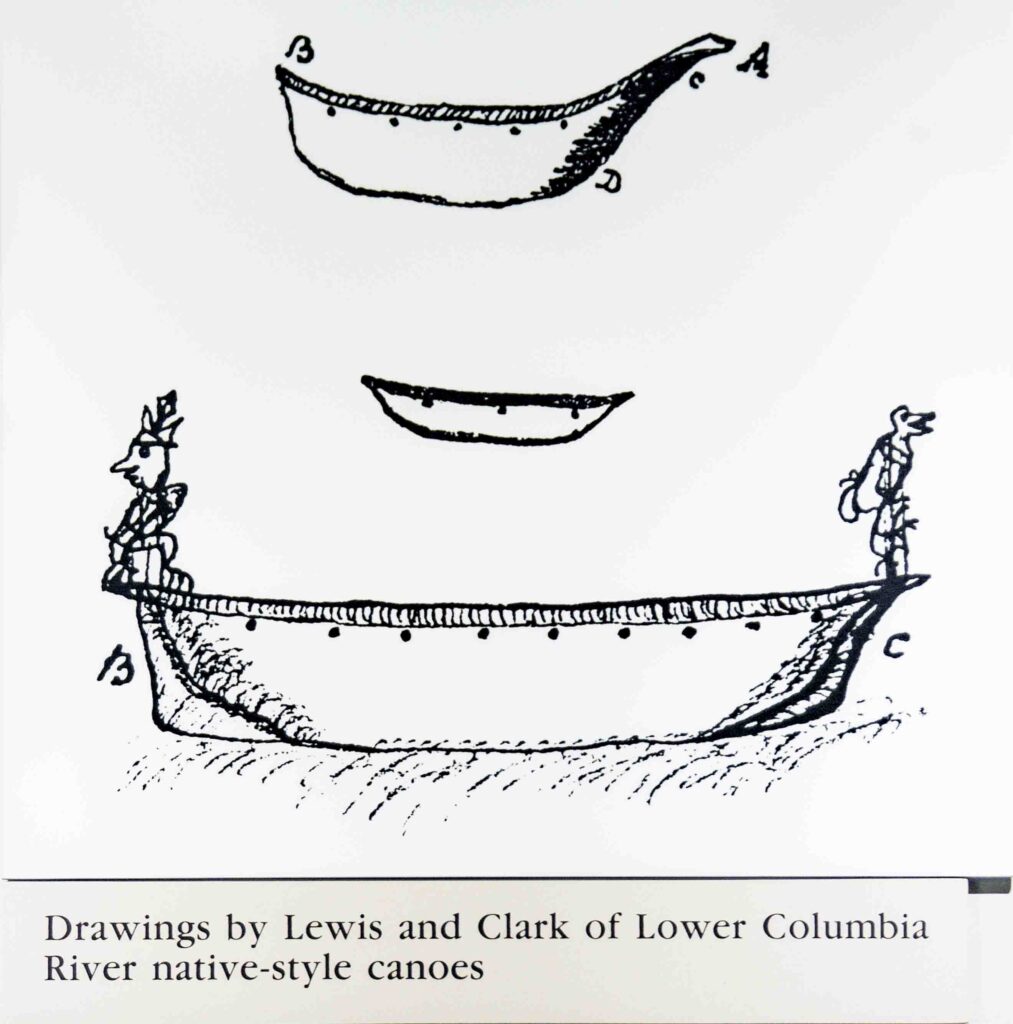

If you look at the water, you see waves coming at us that are wind-generated. You may think small waves like that are no problem; but remember, they’re in heavy, long, dugout canoes that have no secondary buoyancy. They don’t rise into the water like a Chinookian canoe, which goes right through the waves like a cruise missile.

When Lewis and Clark try to round the point, they realize their dugout canoes can’t make it around the point. They return two miles. They went back two miles to the little bay under a high hill where they’d had lunch a few hours before. The high hill that forms that cliff is Eagle Cliff. If you’re sitting on the water, it sticks out and basically dominates this little bay. The 1945 U.S. Army Corp of Engineer map that existed before the highway was built shows this cliff came out another 100 feet. Eagle Cliff was convenient for them because it has small run of fresh water.

At this point, no debris gets hung up and the stream then was clearly visible. They were thankful for that stream because they’d been drinking salt water, getting sick and throwing up for several days while stuck at today’s Gray’s Point– about five miles away. Here there was a convenient stream of fresh water right around a point of land. At low tide there was a beach where they could beach a canoe. They made their first camp from the 10th, 11th, and 12th on this side of today’s Cliff Point. Large rocks were available from this cliff, so when the weather got very inclement and waves got high, they used the rocks to submerge their canoes below the 9’ tides of water. That kept them from being bashed against drifting whole trees and immense pieces of driftwood. Thus, they avoided their canoes being thrown up against the rocks and debris along the shore. This is where they discovered their canoes are inadequate, the weather was brutal, their dugouts would be damaged by being pushed against the rocks.

From this place, they moved their luggage to a small “holler” – an intimate valley canyon – 300 yards from here. On the night of the 12th, the skies opened. It rained horribly and there was lightening. They tried to get around the cliff since rocks were tumbling down on them as the wet debris fell off the cliff face, about 200- 300’ high.

I’ve sat below that cliff during big rainstorms and have heard rocks tumbling off. You can hear them today if you come in a big storm. That night they moved to another camp– not quite 300 yards and found another stream. Clark says they didn’t notice this stream when they first came to this cove because it was covered by brush and debris that hides the mouth of the stream. That’s where they camped the 13th, 14th, and 15th.

JIM SAYCE We are in Dismal Nitch. Crown Zellerbach, a logging company, owned this property till they went bankrupt. What is here now, that wasn’t here before, is the understory!

This logging road brought trees down here to store. We’re now standing on about 15 feet of fill. The original shoreline is 15 feet below us. With all the debris in front of us and 15 feet of fill, you have no sense of the original shoreline. This is an exposed point that got very wet.

That weather certainly affected the men of the expedition. The forest was thick here and went right down to the water. You would make noise going through it and the elk would run away. Your powder would get wet, your flintlock rifle too. You’d put an elk-skin flap over your powder to help keep it dry, but although elk skin is very durable and keeps you warm, it doesn’t keep you dry. Clark had two journals. He kept one sealed in tin canisters and only brought it out during good weather or when at Fort Clatsop. The rest of the time from September 11 until the end of the year, he wrote in an elk-skin journal with water soluble ink.

On this shore, there’s no place to land. But Clark said there was an opening to the ocean in view, which created great joy in their camp. On November 15th or 16th, they arrived at the Middle Village where, for the first time, Clark saw the ocean. A few men had animal skins to protect themselves, but many men didn’t. So, many men suffered severely in the weather because, in fact, they were naked.

RAY GARDNER The weather is why cedar was throughout our entire life. Cedar was used for our clothes, the houses we lived in, our canoes and our paddles. Everything we did revolved around cedar. If you pound cedar bark, as several of our people here can attest, it becomes very soft so you can wear it. For about 90% of the year, if the women wore anything, they wore a cedar skirt. When the weather got bad, they’d wear cedar vests. That was our attire when Lewis and Clark got here.

Everything about who we are and everything we have – even our hats – has always revolved around cedar. We had cedar long houses and established cedar homes. So don’t confuse us with those on the plains who lived in teepees. We didn’t do that here. Some of our bigger homes had up to 200 people living in one home. They were huge, with hand-split cedar planks on the sides and roofs. We had fire pits and could open the roof so the smoke could go out. Cedar was a very important part of all that we were and still are.

PEGGY DISNEY Cedar bark was used for clothing also. They would peel a certain amount of strips of bark off a standing tree, trying not to kill it. Then they’d peel the outer layers off to get to a fine type of fabric within. If kept moist and pounded repeatedly, bark can be almost as soft and flexible as today’s commercial fabrics. They’d line that with fur and animal skins to stop the cedar from irritating your skin. Cedar is also a natural insect repellent, so it kept lice, fleas and any type of jiggers, nits and mites away from the community. Since we use just the very fine inner lining of the tree bark, it’s very supple once you work it. Then the fibers can be woven. By the time we were old enough to be a mother, we were pretty artistic at making clothing.

RAY GARDNER Peggy’s mother was the last of our traditional basket-makers. Her work is phenomenal and is in the Smithsonian in Washington, DC. Many in Peggy’s family have learned from her mother and are now phenomenal basket-makers, and hat makers as well. Everyone learned to make baskets, because in our way of life we needed baskets.

Hats are woven from cedar also. I wore this hat when I testified before Congress and at every ceremony we’ve had since I’ve had it. This hat has more miles on it then probably most people. They’re great rain hats and they’re great in the sun. They keep one cool; and you can look through the weave seeing what everyone’s doing; but no one can see what you’re looking at!

Posted by NWNL on December 17, 2023.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.