A Delta Restoration: Beyond Bees and Bunnies

Mississippi River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

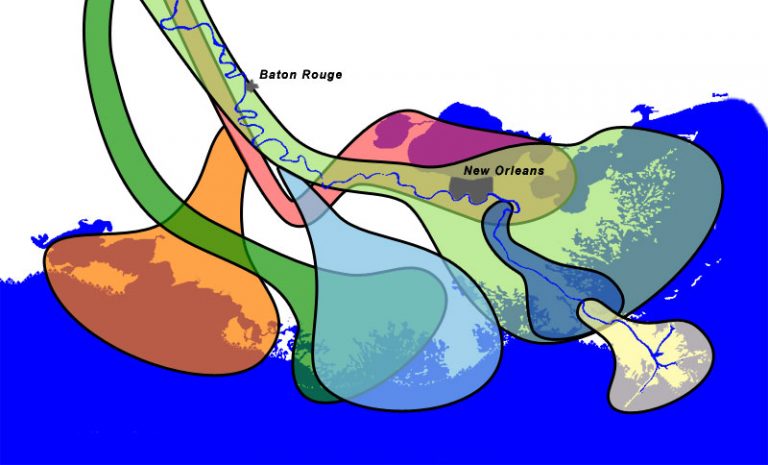

Mississippi River Basin

Amanda Moore

National Wildlife Federation, Deputy Director, RESTORE the Mississippi River Delta in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director and Photographer

Gussie Baker

NWNL Guest Expedition Member

A Delta Challenged

A Clear & Critical Focus

“MRGO” Must Go

Lousiana Oysters

Invasive Nutria

Marsh Restoration

Coal Versus Coastal Master Plan

A Political Will For Restoration

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

This National Wildlife Federation (NWF) program works with The Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), National Audubon Society, Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation (in New Orleans), The Coalition to RESTORE Coastal Louisiana (in Baton Rouge), The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and Louisiana Wildlife Federation. Fortified by restoration successes after both Katrina and the BP Oil Spill, RESTORE’s success models the viability and sustainability of large-scale projects that return fresh water and sediment to coastal estuaries and deltas in a manner that supports or mimics “the river’s natural processes.” The key to their work has been close coordination with local stakeholders, their economy, state legislators and the Federal government.

NWNL Hello Amanda. To start this interview, please explain the importance of your focus on The Mississippi River Delta. Then, we’ll discuss the most critical concerns facing the delta and how your attention can make an important difference.

AMANDA MOORE The Mississippi River Delta, the largest delta in the U.S., provides so many resources for all the communities that live and work in the delta — from seafood to shipping and navigation, as well as storm protection. This estuary is also part of “The Energy Coast,’ since a lot of oil and gas exploration that fuels the nation comes from this delta.

NWNL How would you assess the current condition of this estuary?

AMANDA MOORE We are in the middle of a crisis right now. The delta is dying. We are losing one football field of wetlands in the delta every hour. We have plans in place to help address the situation; but of course, it will cost a lot of money. Yet it’s critical that it happens, because, without it, the country loses a national treasure, and much of the nation’s critical infrastructure is at risk.

NWNL I was at the Jean Lafitte National Historic Park, where they said 1 football field of land in the delta is lost every 40 minutes.

AMANDA MOORE I think there was an updated study in 2010 that said it was every 38 minutes. A later assessment changed it to every hour. So you hear “every half an hour;” and you hear “every hour.” The most recent is one hour, so we’ve changed our materials to hour.

I don’t know exactly why it’s slowed down. We have some land buildup happening now in areas like the Atchafalaya Basin. Since the ‘70s it’s kind of exponentially growing.

NWNL The football field analogy is particularly apt in Louisiana.

AMANDA MOORE Yes. It’s called “social math.” That particular statistic has really taken off, because everybody’s such a huge football fan.

NWNL I noticed that! What other values do you ascribe to the Mississippi River Delta?

AMANDA MOORE Wildlife! Our delta is home to several critical and endangered species, so we focus on habitat connection, the importance of this estuary for habitat, and the millions of birds that use this area on their migration.

NWNL Your organization is a coalition of many groups, including the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and The Nature Conservancy (TNC). How did the coalition come about? Who are the partners? And, why is it important to have a coalition?

AMANDA MOORE One of the wonderful things about my job is that I work with several different organizations, including some big national groups like EDF, TNC, National Wildlife Federation and National Audubon Society. We also have state and local partners: The Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation and our Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana. We also have partners like Louisiana Wildlife Federation that works with us on certain aspects of our project. Our coalition was founded in 2008. We have grown in size a lot since then, and – this is really important—everybody has their role to play. For instance, with NWF we focus a lot on wildlife habitat aspects, working out in the field talking with communities.

Every partner has a different role to play, different levels of expertise that they bring to the table. When we work together on overarching goals and positions, we just have a lot more breadth of power and resources to lend to each other, so we make more of an impact that way. For instance, I work with the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation a lot on certain big restoration projects, with great capacity on outreach and with stakeholders. The Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation has a great local legitimacy and science expertise. Combined with the larger resources of National Wildlife Federation, our name and our brand recognition is greater vis a vis national projects.

And with this larger, broader outreach, we help each other get more legitimacy locally, and we can better bring in a national audience that cares about what we’re doing here.

NWNL Who came up with this partnership approach and its motivating force?

AMANDA MOORE There were many different players. At the very beginning we had people who had been supporting the delta for generations – for decades. So it’s not a new issue here for national groups to be engaged with local groups.

Katrina was a big catalyst for people understanding that 1) there are many different sides to what’s happening in the delta; 2) the problems are real; 3) and the problems are here and impacting us right now. Much attention came into this region after Katrina. We had catastrophic devastation of communities. Some of that was due, in part, because we have lost our storm-surge protection. Losing our barrier islands as buffers isn’t just an issue for the bugs and the bunnies anymore — it’s an issue for actual communities that live here and know the history and the culture of the delta.

NWNL What do you mean about your issues being “beyond bugs and bunnies.”

AMANDA MOORE What I mean is, while restoration of the Mississippi River Delta is critical for wildlife, today’s issues really hit at the heart of people and communities and culture. Thus, the restoration to be done goes beyond a few species. It goes to our infrastructure and our economy.

People are realizing that we are really at risk and need to take action. We’ve been hit directly by the loss of wetlands in our delta. So, for instance, when you talk to communities and people in New Orleans, people care about wildlife, but there are so many other things for people to care about. What will motivate people to get engaged, stand up and talk to their elected officials, and come to public meetings? To reach out to a broader group of people, you have to make it clear that this isn’t just about wildlife and habitat.

We’re focused on our communities, since we are all dependent on the delta ecosystem. We know that every time a storm comes, we need protection; so, we want coastal wetlands. We want to know that we’ll keep our south Louisiana culture for generations to come; we’ll keep our seafood industries, that we’ll always be able to live in a resilient community.

Especially since Hurricane Katrina, I think the community is continuing to consider resilience and sustainability. Probably in south Louisiana and the Mississippi River Delta – more than in many other places in the country – this population really understands how critical those issues are because they have had to live it every day.

NWNL So, realizing that, how did the Mississippi River Delta Restoration Program evolve?

AMANDA MOORE We gained a lot of attention. Paul Harrison, with EDF, had put a strong effort forward towards a restoration movement that would make a big leap forward. Susan Kaderka, with NWF, had overseen and been engaged in this region for some time. She and Paul accepted us as one of their first pass-through fiscal sponsorships, Over the years, we got our own funding streams, but we still work together with EDF and NWF.

NWNL Were there any models you followed in other regions in the world for doing this? Are you becoming a model for other regions in the world?

AMANDA MOORE I’ve been here since early 2009, and I’ve seen our campaign evolve in a big way; but I don’t know if we were are a global model. The Everglades Coalition and the Chesapeake Bay stewards as other national examples. We’ve kind of taken our own course. Every issue has its own quirks, and so we have to respond to that and be flexible. Coalitions can be very difficult, but they’re also very rewarding. I think that we’ve done a fantastic job trusting each other, respecting each other and keeping ourselves very focused on the mission, successful and strong over the years.

NWNL What lessons would you pass on to other regional coalitions?

AMANDA MOORE Well, you always need to stay very focused on your mission. You’ll always be pulled in many different directions. Hot-button issues will come up on the periphery of your work, but if you stray too much, you’ll be open to rifts in the coalition.

I think our success has come from being on the same page and signing off on the same releases. We develop policy stances together, but we respect there are times when you need quick turnaround and can’t get others to sign on. Then we just go to the next issue and focus on moving forward. For instance, I coordinate the MRGO Must Go coalition — which is 17 organizations—and these principles hold true for that coalition, which is more issue-specific. MRGO and this larger campaign both know it’s critical for a coalition to keep away from “mission creep.”

NWNL I think it’s really critical with any organization. When NWNL began in 2006, we said our focus was only surface-water issues, since it’s nearly impossible to photograph aquifers! Well, groundwater’s becoming more and more threatened, and intertwined with surface water issues! So we have to be flexible.

AMANDA MOORE Yes, you always have to be flexible. Things come up, staff come and go, and issues evolve. So you must reassess, reevaluate and have really good communications and structure. We have an Executive Committee, and everybody knows and respects that our decisions are delegated or made within the committee. There are many times where we don’t agree but, at the end of the day, we stay focused on what we’re all there for and move forward.

NWNL So what are your primary focuses?

AMANDA MOORE Many issues face the Mississippi River Delta causing us to lose one football field of wetlands every hour. To start, we have sea level rise. We say we are Ground Zero for climate change here, yet our relative sea level rise is actually partly a natural subsidence of the delta. Sinking land and rising sea water levels are really high on the chart of our threats.

We also have legacy oil and gas canals that really ripped. There’s a really long list of threats to our delta, but I think the big ones are legacy oil and gas canals, navigation canals, subsidence, sea level rise, and hurricanes. Hurricanes definitely impact land loss. Hurricane Katrina tore through the 76-mile-long Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO) Channel and the intermediate brackish marsh, thus bringing saltwater into freshwater ecosystems. Just that one MRGO Channel impacts over 600,000 acres of coastal habitat.

NWNL Please explain the background of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO) and how the “MRGO Must Go” initiative fits into your list of threats to the health of the Mississippi River Delta. The fight against MRGO seems to address a significant challenge.

AMANDA MOORE Yes, it’s a fascinating issue to talk about. The Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO) is a deep-draft navigation channel built in the late ‘50s and early ’60s – before our National Environmental Protection Act. MRGO was built by the Army Corps of Engineers as a shortcut from the Gulf of Mexico to the Port of New Orleans. Many community folks were in support of it, but many were not.

It was quite a debate. We were promised lot of economic gain from it. But this deep-draft channel actually cut through a lot of critical wetlands that buffer the Greater New Orleans Area. The MRGO channel itself destroyed 27,000 acres of wetlands, and then degraded 10’s of 1,000’s more. Just that one channel has altered salinity and changed 600,000 acres of coastal ecosystems and habitat surrounding the Greater New Orleans Area. That includes all the salinity changes on Lake Pontchartrain, which is huge.

MRGO was known as a “hurricane highway” before Hurricane Katrina happened. Right after construction was completed, people saw immense changes in their wetlands. Fishermen and local people that use the area every day spent their entire lives trying to have this thing closed. They said, “This is terrible, and when the right storm comes, we’re going to have some serious problems.”

When Katrina came in 2005, those fears all became reality for the communities. Those with the most catastrophic flooding from Hurricane Katrina were those along the MRGO. They weren’t necessarily the lowest-lying communities by any means – they just lacked protection. The levees built along MRGO to protect these communities were not up to the challenge of Katrina’s direct impact because of the loss of wetland outside the levees. So, the country saw how the Lower Ninth Ward communities were devastated.

In 2006, right after the storm, the “MRGO Must Go” Coalition was founded with 17 organizations. It included big national organizations, and smaller local community groups that had worked together since 2006 to close the channel to navigation and to see the ecosystem restored. By 2009, this was accomplished due to a lot of policy stuff.

We’ve made a lot of progress; and MRGO Must Go is still an active coalition to this day. We have a completed Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) on restoration of this area. This EIS is in the state’s Master Plan and will be the blueprint for a lot of money for restoration in Louisiana. So, the coalition and its MRGO Ecosystem Restoration Plan is still very relevant and active to this day.

NWNL So the MRGO Channel still exists, but without major navigation. What would you like to see now? Would you like to see it filled in eventually?

AMANDA MOORE No. Many folks think that restoration of the MRGO ecosystem is about filling in the channel. But there’s not enough sediment out there to do that. It would be unbelievably expensive. Since filling the MRGO channel isn’t feasible, what we want is to strategically restore the ecosystem and landscape features critical for storm protection — those that serve as major buffers for incoming storm surges. Along the channel we want to restore some of the eroded “bank lines” [shorelines along the channel’s banks].

There are also environmental justice projects addressing communities. For instance, there’s an effort to bring back a dead cypress swamp in the Lower Ninth Ward. Additionally, there are land bridges out there that, for instance, separated a lake from the channel itself, but now there’s no separation anymore. Where land bridges are gone, we restore that land bridge.

We also want to restore historic oyster reefs and fisheries that have been impacted. Much of this requires freshwater input, by reconnecting the river into that ecosystem. There is a plan for a very small diversion up the Mississippi River to help provide that freshwater input. That could restore the cypress swamps that would allow formation of productive reefs. These reefs have been destroyed by saltwater intrusion, since increased salinity changes species viability.

NWNL New Jersey’s Raritan River ends in a bay that flows into the Hudson. There is a serious effort in this estuary to restore oysters, mostly to stop erosion. Sadly, despite recent improvements, the Raritan Bay is still so polluted that local signs warn people of the danger of eating local oysters. However, the poor and unemployed sneak in to gather oysters as free food. Yet, Raritan Bay stewards hope their water is now clean enough to sustain oysters so these mollusks can help further improve the water quality. So are Louisiana efforts to protect oysters meant to counter erosion, clean the water or grow more oysters for harvesting?

AMANDA MOORE That’s a loaded question. Oysters are a very interesting topic in the delta; and we have very productive oyster beds. In the MRGO ecosystem, restoring historic oyster reefs is mostly for stabilization and storm surge protection. Oysters create a natural shoreline natural barrier.

I think oyster management is different for a delta than for a bay. For instance, I’m from the Chesapeake Bay and my family are oystermen. They get a lot of their oysters from down here, because this delta is part of an amazing estuary with freshwater input. But when there are changes, we have to go in and find a way to re-engineer the Mississippi River Delta. When we increase the fresh water to get the ecosystem working again, you’re see many changes occur that are related to salinity.

Oysters can accrete, move up with sea level rise, and filter the water. They are phenomenal. Over time, oyster reefs and beds have moved inland as the delta has eroded, as they seek that salinity range that they need. With our restoration and reintroduction of the river into the delta, salinity changes have impacted these oyster reefs. Thus, oysters create issues to be addressed in restoration.

NWNL It seems that addressing water salinity and protecting oyster beds must also include working with local stakeholders dependent on oyster harvesting.

AMANDA MOORE Working with oystermen and other stakeholders is critical to creating a plan for relocating oyster grounds. We have private seed grounds and public seed grounds. With oyster production, the hope is that eventually oysters will become even more productive when we reintroduce fresh water and establish a more functioning delta.

One hundred years ago, oysters were more productive and plentiful than now. They are still very productive, but the hope is that eventually they’ll become even more productive. But that requires a transition period; and transition and changes are difficult for people with existing productive oyster leases. So, in dealing with stakeholders during transition issues, we hope to help communities move forward to face these issues of sea level rise, saltwater intrusion, and the movement of oyster beds.

NWNL Are there any finfish species at risk?

AMANDA MOORE I’d say there are none at risk. Delta restoration will actually help to expand and increase their freshwater habitat. Even American alligators will benefit, as will many endangered bird species, including migratory species.

NWNL What do you know about the nutria as an invasive species? I hear they burrow into the levees and that eat vegetation that stabilizes the little coastal land that’s left.

AMANDA MOORE Those invasive nutria pose one of the big issues facing the Mississippi River Delta. They are everywhere. They look like a big rat with two huge yellow teeth that make them easy to identify in the wild. And yes, they love to eat our wetlands vegetation right at the roots. This is very problematic when doing wetland restoration or conserving existing wetlands. Nutria take out thousands of acres of wetlands.

So, Louisiana has a program that pays $5 a tail for killing nutria. Some people do that on the weekends just for fun and to make a little bit of money. Some make their living killing nutria. There are a lot of nutria and that program has been successful. It’s really helped manage some parts of the Delta, thanks to support from the Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection, and Restoration Act.

So something is being done with nutria and people keep trying to find better ways to manage them, since they’re still wreaking havoc. We need to protect everything. Groups doing restoration need to build excluder cages around cypress trees. Small restoration projects will be for naught without excluders, so that’s always worked on. I’ve heard many solutions thrown around. Nutria love sweet potatoes, so people have thought about dropping them from planes into areas with lots of nutria to sterilize them.

Federal agencies are always open to different ideas for how to take care of this issue. Now they’re also in the Chesapeake Bay and moving into Maryland. Nutria are definitely spreading, but they’re rampant in this delta. They are a major cause of land loss and a major factor into every restoration project here.

NWNL If sweet potatoes are dropped with some kind of fertility prohibitor, would that be eaten by other species?

AMANDA MOORE That’s a good question – and it’s probably why it hasn’t actually happened. But there are many other different ideas, like what is their natural predator? Alligators?

NWNL Is their spread related to climate change?

AMANDA MOORE I don’t know.

NWNL Let’s talk about the marsh-building Myrtle Grove Project, now referrred to as Mid-Barataria Diversion Project in the Ironton area of Plaquemines Parish. Yesterday, I flew with South Wings over Hermitage Lake to photograph the RAM coal terminals, right next to diversion area.

AMANDA MOORE Yes, there are 600-plus acres of land occupied by those RAM Terminals. Our campaign has been at the forefront of the Mid-Barataria Diversion Project. Medium-sized in the scale of diversions, this project will reintroduce the Mississippi River into a part of Barataria Bay, the fastest-eroding coastal area in the Delta.

NWNL Is the project introducing the Mississippi River or sediment of the Mississippi River?

AMANDA MOORE Both are being diverted which is good. The sediment’s critical. Much modeling work has gone into this, which our campaign has helped pay for years.

Modeling a diversion at the right size, with the right entry for the river, engineered the right way to capture the most sediment, and an outfall designed in the right way, is proof of concept for reintroducing the river into the delta and building new land. When the river’s very high, we will open the diversion to run, so the delta will be pulsed. But we will minimize the diversion’s run when the river’s not high, because only when given certain amount of cubic feet per second does sediment move fast enough to warrant opening it to freshen the basin.

This spring, the diversion will mimic the process that occurs naturally when the river overflows its banks. This project is probably one of our #1 priorities. We’re very, very focused on it, and have been since the beginning of the coalition. This diversion will help us learn to model other major projects.

Editor’s 2020 Updates:

NWNL What about the RAM Terminals? I understand that coal particles from the RAM terminals are in the sediment being lifted into the marsh. As well, a 2012 study by the Water Institute of the Gulf stated the RAM terminals could reduce sediment captured by the diversion by 17%. Is the project introducing the Mississippi River or sediment from the Mississippi River?

AMANDA MOORE The RAM terminals present an interesting, recent change in this story. This coal facility is not a coal plant. It’s just a transfer station basically for the coal.

NWNL I understand this coal comes down by barge from Pennsylvania and Ohio.

AMANDA MOORE Yes. The issue is that the RAM Terminals are sited very near the intake for the Mid-Barataria Diversion Project. They are not exactly on it, but close enough to have some impacts. It’s interesting that the State of Louisiana moved RAM forward, because the state is also responsible for the Mid-Barataria Diversion Plan. The question is what takes precedence: industry or restoration? This is an interesting case study. Because of this juxtaposition, the public is really engaged as they see that juxtaposition.

It’s been an interesting way for people to get engaged with very scientific and engineering-based issues. I don’t know how it will end, but the state says they’re fully behind its “Master Plan for a Sustainable Coast,” passed unanimously by our legislature in 2012. This diversion is one of the premier projects in that Master Plan.

NWNL I have heard that 20% of that Master Plan is funded, but nobody knows where the rest coming from. Should it come from oil and gas industry?

AMANDA MOORE So, after Katrina, the state came up with a process for creating master plans for coastal protection and restoration. They include levees and restoration projects.

In 2007, they released their first one, to be voted on by the entire legislature. It didn’t really have price tags associated with it, so didn’t have a lot of teeth, or cause much of a stir. Every five years, they have to create a new one. In between, annual plans are passed with progress updates. Here in Louisiana, 2012 was a landmark year for restoration, because we really engaged and passed a Coastal Master Plan. They had many teams. Focus groups, development teams, and stakeholder groups were engaged. The best science from all over the world was involved in the modeling and projections, as we figured out which projects we should we put forward; devised a timeline; and set a realistic price tag.

What evolved was a 50-year, $50 billion plan with almost 200 projects. While the State Legislature passed the Master Plan unanimously. Inevitably, decisions were made that we could not save this entire delta. It can’t happen. We have to pick and choose which levee projects get funded and which restoration projects get prioritized. For example, the entire iconic “Birdfoot” is left out of the Master Plan since it’s really not savable at this point. It’s not sustainable.

The Master Plan’s focus is on certain areas, certain ecosystems and certain basins. The plan is the state’s blueprint for prioritizing billions of dollars coming back to the Gulf after the massive BP oil spill. These Clean Water Act penalties were assessed per barrel by the 2012 Restore Act. Our Master Plan is considered to be a leading, cutting-edge plan for the entire world. We have a real “real estate plan.”

Of course, the plan is not perfect. The state and the stakeholders recognize that, so already a 2017 Master Plan is building off of the 2012 plan. In terms of funding, it’s $50 billion over 50 years, and the state only has so much money. The vast majority of funds from the Deepwater Horizon disaster’s Restore Act is protected. Some federal revenue from oil and gas is also coming into the state for those purposes. I think, in a lot of cases, restoration will be done at the community level. After Katrina, the City of New Orleans had a $15 billion restoration system from the federal government to work with. Some communities are taxing themselves to pay for local levees.

We have a wonderful infrastructure here to protect the communities, but how do you pay for the upkeep on it? A lot of money, needed for yearly maintenance, is being handed over to the local levee authorities. This money has to come from a tax base. These are some real questions facing us in terms of funding for not just the restoration. It’s also for levees.

NWNL Will New Orleans still be here in 2070?

AMANDA MOORE Yes. New Orleans will be here, but I don’t know what the coast surrounding New Orleans will look like in 2070.

If we get serious about funding restoration and get it moving, we can show that this process works. I think one huge ramification is that this blueprint could be beneficial to the nation and the world as we face climate change. We can all use our rivers to help maintain our coast and habitat in the face of sea level rise. I think that we will have communities still living here in 2070. It’s going to look different, but this port city will still be functioning.

I think without our restoration, you would see a walled area — with not much else outside of it and unable to withstand the storms that come into the Gulf of Mexico. We will have very vulnerable communities that are not resilient, and so if the right storms come at the right time and our people keep staying here…. Well, I think the resilience and sustainability of these communities depends on maintaining and sustaining our coast. We can do this, but it is going to take the political will to do it.

NWNL So in building that political will, who’s your audience? Is it the State House, the White House, or Congress? Is it the local people? Is it the oil and gas industry?

AMANDA MOORE Our audience is very broad. We want to target our messages and outreach for specific times and the right people, at the right opportunities. Who are those players and decision-makers? They come from the White House and Congress. The federal agencies are always very involved in permitting all that happens here. Congress has the political will and appropriations to make things happen. But to get Congress to act, you need to have the people engaged. Sometimes that just means activating our local base to inform Louisiana legislators. Sometimes it means activating national audiences and groups on what’s at risk here and what it means to the rest of the country. That’s what we did with the 2012 Restore Act after the BP Oil Spill. So, our audience is really all of the above.

We have to engage all local stakeholders: people working on the water and communities using water. We need them to share our vision for where to go. I think there’s broad agreement that we have an urgent issue, critical to our future. I don’t think anybody would disagree. But it gets really difficult when we ask how shall we do this, and where do we draw lines, and who’s going to fund this? There are many tough questions beyond general awareness.

We have some funding. We now need to make very strategic decisions. It’s real. We have to pick projects. We have to start moving forward and doing so is going to impact people. The impacts are not always going to be easy for everyone. There’ll be transitions involved. The audiences are complex and there are many layers of decision-making. That’s what we do, and we love it.

NWNL I’m glad I asked that question. I keep thinking that whether here in Louisiana or elsewhere, all of us must get to a point of YES, as defined in a book from the ‘60s called Getting to Yes. We’ll need to learn to work together to find the win-win scenarios.

AMANDA MOORE It’s really hard.

NWNL Always seeking solutions, I was interested to learn about Louisiana’s Green Army. Is your organization a part of that?

AMANDA MOORE Yes, we are involved with the Green Army since many of our partners – like the MRGO Coalition – are involved with it. It is led by General Honoré, who was something of a Katrina legend, and John Barry, who wrote Rising Tide, a very famous book in this area on the history of the delta, what happened to the river, and how we got where we are today.

Both leaders are iconic here. They care about the health of the coast and are rallying many community groups and organizations to discuss water issues. They talk about water quality. They are involved with the oil and gas lawsuit. For our part we’ve always stayed very, very focused on delta restoration. That’s what we work on.

NWNL After my interview with the Army Corps of Engineers this morning, I had a taxi driver who graduated from Vermont’s Institute for Social Ecology. Then in the 1980’s he was very involved with Ralph Nader in starting the Green Party in the ’80. He went on to be a teacher. He’s passionate, concerned, and knowledgeable — yet he’s not involved. How would you recommend a local person who follows environmental issues get involved?

AMANDA MOORE There are many different ways to be involved. Some people want to plant cypress trees, and there are plenty of opportunities to do that. It’s wonderful and many of our partners do that. There’s also the policy side of things. For those who want to go to public meetings, we’ll brief them and send them to congressional staffs or public meetings. We need Letters to the Editor written, and creative ways to use social media. Folks can generally find something that fits.

NWNL Do you help people engage in advocacy and policy work?

AMANDA MOORE Yes! Our outreach staff talks to community groups to find those who are passionate and might want to get involved. We offer opportunities to learn more about the issues; we give briefings; we give general guidelines for how to write Letters to the Editor. When the legislature is in session, we need help with email or phone campaigns. We encourage “coastal warriors” to engage with community advocates, their city council, and legislators at the state and federal level.

NWNL Are you the best organization for them to contact?

AMANDA MOORE Well, we partner with many fantastic organizations that provide ways to get engaged. You can go knock on doors all day with the Gulf Restoration Network, for instance. You can do phone banks with them. You can get learn to give presentations to your networks, community groups, or legislators here or in D.C. We facilitate meetings with well-versed community leaders that can be comfortable. We can explain the pulse of what’s happening, where the decisions are being made, and help folks guide their friends and families.

It’s so important to elevate our voices so our legislators know that they have broad support – and not just from environmental groups like us. Legislators want to hear that your taxi driver really cares, and people on the street are really worried. We underestimate the power of our voice, of talking to our legislators, of writing to an editor and of attending meetings. It is powerful when people take the time to go stand at a mic, or comment about why they care on the coast, or take an hour to meet with a legislator to say, “Listen, I’m really concerned about this. What are you doing?”

NWNL My taxi driver said, “It’s time. I need to get involved. My afternoons are free. I really should get more serious. How do I do that?”

AMANDA MOORE To get involved with our campaign, go to: Mississippiriverdelta.org. We have great information there and a take-action-and-contact-us page that is really easy to use.

Or just go ahead and send a letter in to decision-makers. Let them know what your priority is, and what we should focus on. Contact us to be in touch with our field team that works all over the coast. We have fantastic people who’ll be happy to talk on the phone and help you find the best way to plug in.

NWNL All great advice! Thank you so much, Amanda.

Posted by NWNL on February 25, 2020.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.