Regal Fritillaries in the Platte River Prairies

Mississippi River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Mississippi River Basin

Andrew Caven

Lead Biologist, Crane Trust

Soil impacts on Regal Fritillaries

Grazing and Fire Management Impacts

The Butterfly Prairie Paradox

Transect Sampling

The Wildlife Survey

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

On arrival at Nebraska’s Crane Trust to view the sandhill crane migration, as it paused on the Platte River, we learned we could hear the Trust’s renowned biologist speak about the endangered regal fritillary butterflies in the Nebraska prairies. This unexpected treat offered yet one more lesson in the interconnected aspects of insects, birds, soil, fire, and the presence and amount of water. Dr. Caven specializes in conducting biological and ecological surveys, as well as long-term environmental monitoring of cranes, buffalo, small mammals and songbirds, as well as bats and butterflies.

Today’s talk is about the regal fritillary butterfly (Speyeria idalia). Most people are very familiar with the monarch butterfly and similar species. Actually, the monarch and the regal fritillary are both in the same family of butterflies. The fritillaries have been experiencing a really precipitous decline and are probably even more at risk than monarchs. They have been considered for the endangered species list for a number of years, probably because there’s very little data on them.

Where exactly do they persist? Historically, they’re an endemic tall-grass species, meaning they really are found only in tall-grass prairies. The tall-grass prairies used to be extensive from Ohio all the way here where we’re at the western end.

The only reason we have tall-grass prairies here is because of the Platte River. The roots of these tall grasses can reach down into that riverine water supply, because if you go five miles north or south of the river [which runs eastward to the Missouri River], you’re into mixed-grass prairie. Thus, we have this population of regal fritillary butterflies out here.

Our study has determined under what context the regal fritillary persists. It has been shown that over the last twenty years, this butterfly has declined by an estimated 75% to 95%, depending where you look. Areas like Iowa that have less than 1% tall-grass prairie are among those many regions where regal fritillary populations are not intact. Areas like ours here in the western part of their terrain are large enough to support this butterfly. Thus, the western part of the terrain where we are, may now be their last stronghold – even though historically this area has probably not been very important habitat for the regal fritillary.

Our map kind of tells the story. It shows only one state that comes up as apparently secure. That’s Kansas – specifically the Flint Hills of Kansas – where the soils were too thin to really ever have very extensive agriculture. However, that could change now with new technology. Historically, this region in Kansas has been a place with a lot of ranching. Fritillaries can persist if there are ranchlands that are managed appropriately. But according to the rest of the map, fritillaries elsewhere are either endangered, imperiled or vulnerable. Nebraska is vulnerable habitat for this species. In Iowa, they’re in peril. So, this species is not doing particularly well. Where it still persists, there’s been a big effort to figure out why they still persist in that habitat. Historically this butterfly is found in Crane Trust’s lands and Rowe Sanctuary locations.

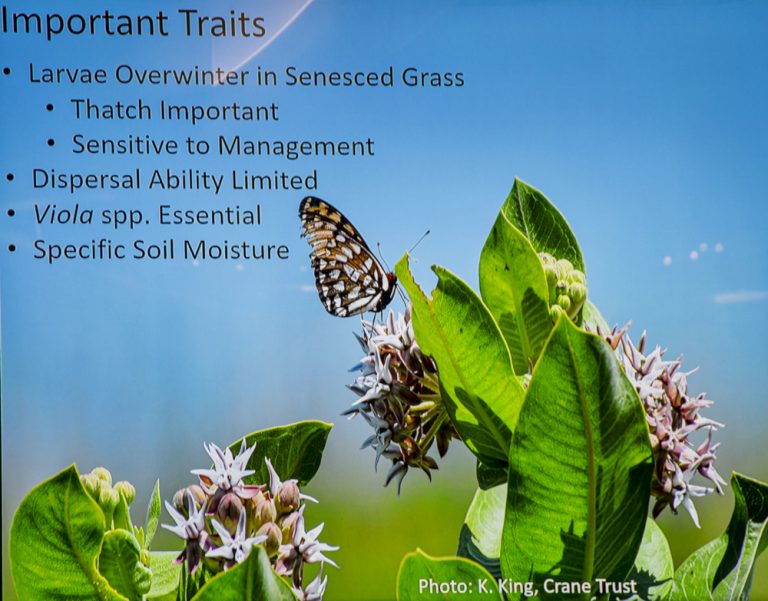

Part of our study is to determine what makes this butterfly susceptible to localized extinction. The larvae overwinter in grasses. Yet one thing that we’ve done as a conservation community to maintain this region as it once was has been to introduce fire. Historically, fire would have burned through these large prairies, but there would have been adjacent tall-grass prairies as a refuge. However. now, as these parcels get smaller and smaller, there’s a concern that fire over too high a frequency and over too large of an area can actually impact regal fritillaries, because they remove that thatch that’s important. So these butterflies are very sensitive to management via grazing and fire, but particularly fire. We know that from the literature.

Fritillaries also have a limited dispersal ability. Studies have shown that they have not recolonized in prairies, even those that are short distances of a couple of miles away. A restored prairie may be separated by a farm field or two from area which contains these guys, but they don’t recolonize to the restored prairie. We are seeing they may require a very specific soil moisture. The soil can’t be too wet, can’t be too dry.

Now let’s discuss the importance of “thatch” to this butterfly. Grass grows; and thatch is just dead material connected to that grass or other live plants, like a yucca. Fritillaries need that extra material of thatch attached to grass. They lay their eggs in those sites; and as research has shown, these microsites protect their eggs over the elements and through the winter. Under these microsites are violets. Where you don’t have violets, you don’t have regal fritillaries.

The properties that The Crane Trust conserves, manages, is responsible for, or owns is up and down the Platte River. There are a lot of properties conserved by the Nature Conservancy and Audubon, Rowe Sanctuary, and the Platte River Recovery Program; but still, in total, only 3% of tall-grass prairie in Nebraska is still in existence. The fact that 97% of tall-grass prairies have been eliminated kind of tells a story of the primary driver of this butterfly decline. Every year we lose about 20,000 acres of rangeland that’s predominately being converted to corn.

Preserving these prairies is extremely important; the other thing is that some evidence suggests these rangelands also cannot just be left unmanaged. Historically we had large fires here. You guys have heard about fires. Remember the 60-mile-an-hour winds we had here about three weeks ago? There was a fire this morning. Historically, when we didn’t have today’s roads and farms that break the prairie into separate chunks, that fire could have run 100 miles.

A study published back in ’76 was one of the first documents that looked at which shrubs would overtake the grassland without management for fire and grazing. Cattle graze in one area for an extended period of time, whereas bison would have gone through in pulses. Extended periods of grazing without fire open the ground up to things like juniper berries that germinate at a higher rate. So we’ve looked at differences over 35 years, where one pasture was consumed by fire and the other one wasn’t. Change doesn’t take long, and evidence suggests that once land has evolved without fire evidence, the regal fritillaries can’t use it.

So at the Crane Trust, we used fire to study what’s called the Butterfly Prairie Paradox. The problem is you need fire to keep those juniper shrubs out so cattle can graze. But these butterflies need that thatch material in the grasses that I was talking about. If they don’t have thatch to protect them, and if you burn a whole pasture, you could eliminate all the thatch and thus fritillaries from that area. Historically a part of a prairie would burn, but a river would be the barrier protecting from burning intact pasture. The species would survive because the larvae would remain in the pasture that didn’t get burned. But if you have a cornfield all the way around and you burn that whole pasture killing all the larvae, you could eliminate that butterfly from that pasture in just one year. So we need fire to keep shrubs out and make it appropriate habitat for the regal fritillary.

We need to maintain areas that have thatch for the larvae. So how do we do that? One study says you need at least 7 or 8 years after a fire for an area to serve as a refuge for these butterflies. Another study said nectar in a grazing section of pasture will focus the cattle to graze there because cows prefer fire-burned pasture because fire increases nutrients in burned grass. That phosphorous is released back into the soil, which attracts bison and cattle. And these butterflies benefit from that. If you use a 3- to 4-year burn cycle but leave enough thatch, these butterflies can function.

There are competing views for best management. Some suggest that if you have a big pasture, you should burn only a quarter of it each year. But either way, you can’t burn the whole thing. So now our methods here are to set up transects as a permanent sampling lines, randomly placed in different zones. They’re called “eco domes” with a similar land-use history. The question is whether they were ever tilled, are they restored, or have they basically existed “as is” for the last couple hundred years? What’s the soil type, the land-use history, and the current plant community?

We’ve randomly placed 60 of these transect boxes throughout the Crane Trust property. We use the same methods, year after year as we track trends in the transects’ plant communities and wildlife, including these butterflies and birds, given our different management techniques. This program gives us that ability to see what a transect looks like one year after a burn. How did these butterflies do? How did the birds do? How did the bird community change? This method helps us keep track of what’s on the landscape and how it’s responding to our management. Its data also lets us compare different sites, different soil types, etc….

In New Mexico, soils were studied in concentric rings. You had areas where water pooled in the middle, kind of like larvae. In water basin wetlands you have a soil type based on moisture and concentric rings. But here along the Platte, historically there are huge floods right in the spring. People say the river is a mile wide and an inch deep; but there’s some evidence in historic studies on how wet the soil was historically or that a flood could have been three-and-half miles wide. This huge, expansive wetlands explains why the sandhill cranes and whooping crane historically came here. Well, in the spring when they came, every time they landed, they just pushed the soil down, creating little sandhills and this crazy mess of soil.

While we sampled for both regal fritillaries and monarchs, this discussion is just about the regal fritillary, and there are just 200-meter transects. We counted the butterflies within ten meters, and outside of ten meters. We tried to do it during appropriate weather – mostly sunny with low wind. We visited each site at least three times in the regal’s active period, and at least once during the peak activity period. We’ve realized regal fritillaries don’t move very far, so our study site’s just about 1,300 acres,

Wildlife transects include small mammal surveys, bird surveys, insect surveys and butterfly surveys, as well as vegetation transects. This is where we get all our species information. These vegetation transects show us which plants are associated with the presence of these butterflies.

We have well over 30 soil types on our property involved in creating those little transect zones. For each land-use history, soil type and plant community, there’d be one of those transects, so we can compare how well different soils provide habitat for regals, or not. It’s kind of interesting how crazy the soils of the Platte River Valley are as a result of this historic recurrence of floods just pushing soils around. We can see how different flooding frequencies and 15 different soil types affect the presence of regal fritillaries.

Posted by NWNL on January 16, 2020.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.