Chinook Chief on Columbia River Threats

Columbia River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Columbia River Basin

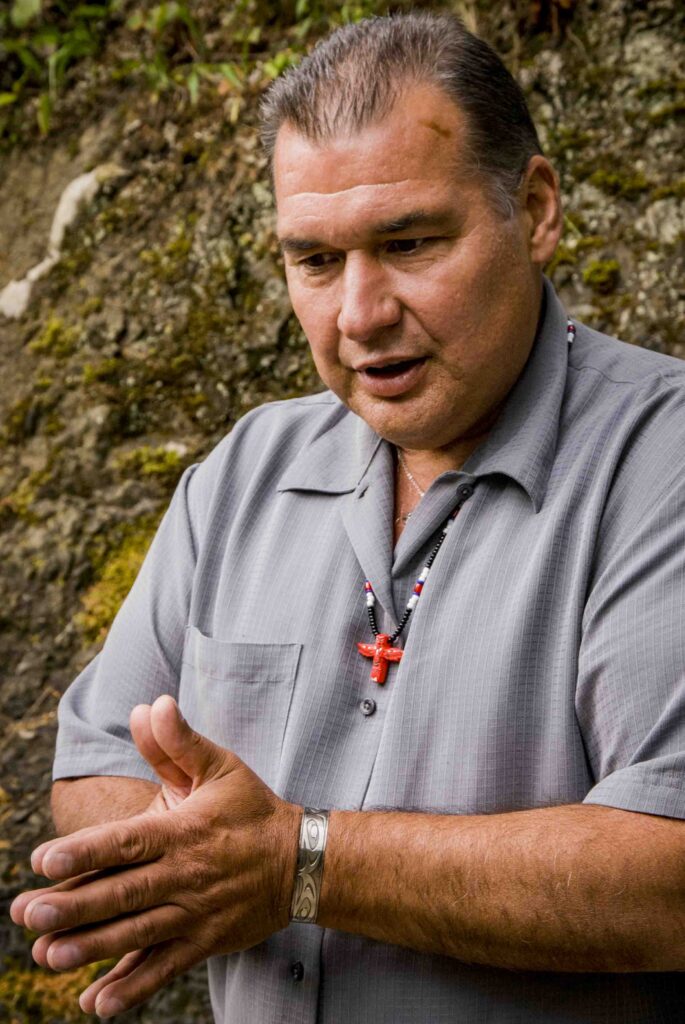

Ray Gardner

Chief of the Chinook Tribe

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director and Photographer

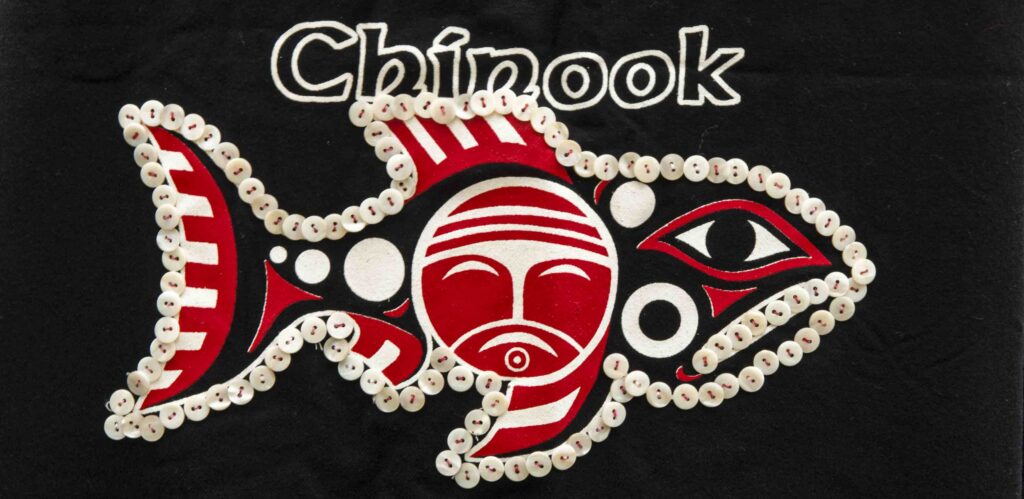

This interview follows our first conversation with Ray, when he discussed the Chinook Tribe’s heritage and leadership in the Columbia River Basin. Our chat centered on the Chinooks as environmental stewards of this transboundary river flowing down from the Rockies in British Columbia as it passes this cove just a couple miles east of the Columbia’s confluence with the Pacific Ocean The Chinook Nation’s presence in this terminal reach of the Columbia has always revolved around the importance and massive annual salmon migrations from tiny upstream habitats where fingerlings hatch to the end of their odyssey to the ocean where they mature for several years and then swim back upstream to spawn. The huge numbers of salmon in these migrations were the core of the Native American’s diet and well-being. The Chinook are dedicated to protecting the health of the Columbia in order to support the salmon and thus it’s no coincidence that one of the salmon species that travel the Columbia carries the Chinook name.

NEGLECT of the COLUMBIA RIVER SYSTEM

ALIEN MARINE SPECIES & PULP MILLS

SOLVING WATERSHED THREATS

FISH FARMS

CONSERVATION CHOICES – STRONG VOICES

THE ROLE of EDUCATION

ONGOING IMPACTS of AMERICA’S TRIBAL PEOPLE

Key Quote Along the entire river system there has been a history of neglect. — Chief Ray Gardner

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

NWNL Hello again, Ray. Yesterday you discussed the Chinook heritage and values. Today I’d like to discuss issues facing the health of the Lower Columbia River today as you and the Chinook tribe see it, the values, the threats and issues you would like to see addressed.

RAY GARDNER Along the entire river system there has been a history of neglect. Industries have come and gone, but we worry about what those industries have done to pollute the rivers. The Willamette River, just upriver, was tagged as a Superfund Site because the contaminate level there was so high.

NWNL The Willamette River flows past the City of Portland and then into the Columbia?

RAY GARDNER Yes. We look at how the federal government is caring for the Willamette, a river where many industries put arsenic and things into the river. Fortunately, they are now gone because enough silt came down and capped off many of the pollutants. So, there’s a positive side to the condition of this river. Mother Nature – or Mother Earth – has a very distinct way of healing herself if we help her and let her. That has happened on the Willamette.

NWNL Ah, natural attenuation, as the scientists call it.

RAY GARDNER Yes. But now they’re looking at how we deal with this huge pollution problem. Do we dredge the river, which one solution they’ve proposed? But will everything that has been capped be brought back up to float down into the Columbia to the mouth of the river? That would put all those contaminants right back into the river system again.

They suggest waiting to see what Mother Earth will do on her own. Can we just let this sit and insist industries don’t let this happen again? Will she heal herself? The Willamette is one of the most polluted areas that flow into the Columbia.

We have other issues all the way up and down the river, such as port facilities that bring in the ships with logs, automobiles and such. River contamination goes beyond what they spill – be it diesel or an “inadvertent” discharge of bilge oil over the side. By the way – there is no such thing as an inadvertent discharge of bilge oil over the side. That’s just how it’s classified. There are also microorganisms that attach to those ships’ hulls in tropic waters that are now being brought into our waters. Our marine life is not used to those organisms.

NWNL Those alien organisms include mussels and other shellfish?

RAY GARDNER Yes. Shellfish, salt-water algae and moss attach to ships’ hulls. Once in fresh water, they break off in our ports. They then die or settle down into the river and integrate into this system.

As well, odd frogs and fish are being caught or seen. They obviously come from pollutants being put in the water that these creatures live in. So, that’s a hazard in and of itself.

Another problem is that pleasure boats, going from one water system to the next, carry foreign organisms with them. The states are now forcing boats to be pressure washed as they come out of one water system and before they go into another water system. Then, the boats are tagged that they’ve been cleaned. That solution could be applied to these tankers…. Isn’t there some way that they can cleanse those hulls before they come up the river?

We also have the pulp mills on the Columbia, especially the big one up in Wauna, Oregon. Pulp mills have always been notorious for spilling pollution into the water. We have pulp mills not only on the Columbia – but not on the Willapa. Going north, the next river system is Gray’s Harbor, which has the same problems with pulp mills as the Columbia River has down here. Any chemical spills of bleaching agents and other agents they use, would be devastating to entire runs of fish, especially if as they’re coming through as fingerlings. Chemical spills will kill those young salmon when they’re coming through.

Pulp mills and industries have been allowed to continue operations using obsolete equipment. Look at today’s technology, containment vessels, and everything else we have that can capture, isolate and keep contaminants out of our aquifers. Yet we’ve not put proper laws in place to force these industries into compliance with modern technology. So, they’re operating catch tanks that are 50 or 60 years old; and they’re operating with pipelines that are just as old – so they leak, and they break.

There are solutions that are costly to industry, but will protect our environment. In our pipeline systems, today’s technology can force a new pipe inside the existing pipe, thus providing a 99% chance of nothing leaking. There used to be clamps at sections where pipes came together. Before, such a clamp, bolt or anything on that joint could fail and cause leakage. Now new pipes going in are solidly welded, so there are no fittings to fail. The machinery they have now to make those welds is phenomenal.

I’ve watched some pipelines being built and then pressure-tested via air, water and other means. I’ve yet to ever see one of those seams leak. That pipeline technology is done with laser guidance to ensure perfectly square edges and perfect welds. Furthermore, welds now become even stronger than the materials to which they’re adhered.

NWNL That’s good news for protecting freshwater quality!

RAY GARDNER Another industrial threat has been industrial catch tanks and ponds. But today liners are being made for these containment catchments. Now an industry can shut down its operations; clean out the basin and scrub it; and put in one of these liners. That stops leakage into our aquifers, as well as overflows that end up in the river.

I am on the Chinook Tribal Council and Chairman of our Fisheries Committee which keeps me closely tied into what’s going on with the fish in our rivers. We look at these issues I’ve mentioned as our problems and seek solutions. The technology is there to repair it. Solutions we put in place today will allow Mother Earth to start healing herself.

I need to add one other piece not yet here, but I see it coming….

RAY GARDNER People don’t realize the devastation of these fish farms to their nearby river systems. An average-size fish farm puts the same amount of fecal matter into the river as a town of 5,000 people. As we all know, we can’t dump our sewage directly into the river if it is to survive, but fish farms do exactly that. That’s the worst of what they do.

But go beyond that to consider impacts of the escapement of their hybrid fish into the rivers. They spawn with some of the fish in the wild runs and what happens through cross contamination of these hybrids? Will they destroy the native species?

NWNL Yes. I interviewed Paula Burgess and Sasha Twelker from The Wild Salmon Center in Portland just two days ago. They believe we must focus on the strongest of the species –and that the wild salmon are the strongest fish. They are very concerned that we must protect our wild species. They warn that if the hatchery species become too prevalent. they will take over the ecosystem, eat the food that’s there, and the wild salmon will be not able to prosper, even though they are the stronger species.

RAY GARDNER Yes. That’s something again that we also are looking – as well as other tribes. Speaking for the state of Washington and what they tend to do in their hatchery systems. Over time, one of their hatchery system’s goals over time has actually been to eliminate the wild fish, and replace it entirely with hatchery stock.

We have many smaller hatcheries around here. In our state, it’s not frequent but it’s also not uncommon that, through neglect or faulty systems or whatever, alarms don’t go off; filters get plugged; ponds then lose their supply of incoming water, and so the water loses oxygen. Then 30, 40, or 50,000 fingerlings are dead.

We can’t continue to have that happen and at the same time continue to even begin to think we’ll have a viable return of fish. It’s very disheartening. I see this happen when wild fish come into the hatchery system instead of going down river. For years, the tribes have said, ”Let the native species go; they’ll take care of themselves.” But instead, fisheries kill them to take them out of the system. By doing so, they preserve their hatchery stock and slowly decimate our wild stock.

For the Chinook people there are many kinds of salmon we have here: the Chinook, the Chum, the Silver, the Coho, and the Dogs. As far as salmon to eat, Dog salmon is the least desirable – which is probably why it got the name of Dog salmon. But to smoke, it’s the very best fish. Many of our tribal elders are always trying to find Dog salmon to smoke.

I know one of the Columbia’s tributary rivers with Dog salmon. My uncle went there as a child with my great-uncle to see when Dog salmon came into the pens. Even then, hatcheries weren’t doing much with them. My elders wanted them to take them home and smoke. Then they noticed a big pond of salmon that were predominately Dogs. They asked the hatchery what they were going to do with them. They answered, “Well, we’re going to wait until the rest of that run comes in and then we’ll process them through.

Well, they went back 1 week later. The hatchery had drained all the water out of that pond – killing the entire run. To this day there are still no Dog salmon in that river. They eliminated that run of salmon from that river entirely. But all species of salmon have their own purpose for being in those waters. They’re all – each species – part of that integral system that keeps everything running the way it’s supposed to. So that loss of Dog salmon is a problem for the rivers; but that again can be fixed.

So, do we continue to allow hatcheries to operate as is? Or, as concerned tribal members and citizens, do we voice our concerns and institute changes? Change will never happen if people sit back and say nothing. We must stand up and say this isn’t right; this is why it’s not right; and we need to change it. We can do that at a city level, at county level, a state or a federal. But as a democracy if enough people want something done, it’s the government’s job to make that change.

But government will not make a change unless people tell them it needs to be made. As a rule, the government doesn’t sit there and come up with solutions. It deals with crises at hand. Unless someone comes and provides them with a solution, they’re not as apt to act on it. For years when hatcheries would kill the fish, they didn’t put the carcasses back in the river because they said it was harmful to the river. Well, that’s what the other fish ate off of, what the crawdads ate off of….

NWNL That’s what’s happened in nature for thousands of years!

RAY GARDNER Yea. In the last 10 years they’ve started allowing people to put the carcasses back into the rivers. We’re starting to see a little improvement, but it will take more than 10 years to change 100 years of bad neglect.

NWNL Speaking of voicing concerns to the government to engender change, I’ve heard many active voices coming from tribal nations along the Columbia River. It seems, and has been suggested to me, that it’s the tribal voices today that are taking the lead in pushing for protection of this great river.

RAY GARDNER Yes, we are – and it’s been nice to see. It goes beyond just the protection of the river, and it’s important to share all sides of that concern. The tribes have realized what a tremendous voice they have. We’re the only people that can say what was it like years ago. What it was like before colonization. What it was like before industry. We can speak to those things. We are the only ones that have that history, that can say this is the way things used to be and that when it was like that, things were well. We didn’t have today’s pollution problems.

We’re starting to realize that we’re the only ones with our knowledge; and that if we combine our voices, we’re a very large group of people. We are 2,000 people here, 5,000 people here, 10,000 over here, another 1,000 here. When all start voicing the same thing to their state and federal representatives, they must be listened to. For so long, we were little splinter groups of tribes. We were voicing our own little concerns – but not on a united front.

NWNL What catalyst brought tribes together, awakening them to this new awareness that together they have a large voice?

RAY GARDNER I think probably one of the biggest things that happened locally for our tribes was about 12 years ago when a person ran for Supreme Court with a 100% voting record against tribes. Several tribes realized we cannot afford to let this person be elected, despite being 40 percentage points ahead. The tribes used email and other modern technology. Obviously we do adapt. In the state of Washington, there are 29 recognized tribes and 12 non-recognized tribes. When all our people vote together in Washington on a state-wide ballot, they can change an election. And that’s what happened.

NWNL What percentage of Washington’s population are tribal members?

RAY GARDNER It varies from region to region in the county as to our population versus county population. We’re probably about 20% in this county, though we’re a smaller tribe.

Some of the larger tribes are over on the plateau which also has an impact on this river and its life. Now they’re probably up around 35-40%. So, when you look at the elections on the state level, and especially on county level, most of them in the last 10 years were decided within a 5% margin. So, tribes are realizing that if they band together, they are a large enough percentage that even if they can’t sway the election, they can get their attention.

Now with tribes setting up more businesses up and more wealth coming back into the tribes as a whole, not just the individuals, they’re unfortunately realizing that they can even get into the game of politics. The ugly side of it is – to whom should they donate? But at least they get the voice or the attention of that individual.

For the last 10 years, the tribes have been sticking together as a unified voice. It’s nice because it brings together tribes that don’t necessarily like each other but are now realizing they need to work together to make things better. While they perhaps would just as soon wish the other one wasn’t even there, they have found that they can get past their issues – not insignificant, but insignificant in the grand scheme of how we protect our river and life. Anything less than that is very minor and they’re realizing that they can move on to the bigger picture.

I think part of that has come from education. As the tribes have progressed and have more people involved in governance, they that are now getting more education, and thus are now able to work in fields that tribal governments were not in before. They now understand how politics and corporations work, who they need to talk to, and who can make the decisions. For a long time, tribes were not talking to the right people.

Part of that was pushed on them by the federal government. The very first treaty, the Treaty of Delaware, clearly established the chief of that tribe was the equivalent of the president of the United States. But as tribes moved west, they slowly diminished tribal leaders’ status, finally seeing the chief of the tribe equivalent only to governor of the province. So, over time they believed they had to deal with the state governor who then dealt with the federal government. Starting to review that, they’re now getting into the positions with the people that can make the decisions happen.

NWNL Many of the decisions that the tribes are working on seem to be focused on the Columbia River, the watershed, environmental issues, and the salmon. Up near Kettle Falls, the tribal habit is to eat the fish they catch in their entirety. When you eat all of the fish, you consume more contaminants. And sadly, fish absorb and carry a higher percentage of contamination than the water itself.

RAY GARDNER Many tribes’ main sustenance for the entire year is salmon. They eat it when it’s fresh, they smoke it, they dry it, and many people still make the powder out of it. We absorb a lot of that contamination. Delivering fish to elders is probably the best thing that I do for the tribe. It’s so wonderful to pull into an elder’s driveway with a tote of fish in the back of my pickup, open it up and ask, “How many do you want?” I feel like Santa Claus because many of our elders would still eat salmon 7 days a week if they had access to it. So, yes, tribal folks, as a population, do eat more of the fish that come out of this river than any other group.

NWNL Is the health of salmon populations as much a motivator for initiating and instituting healthy policies for the river as is the spiritual belief that its your responsibility to take protect Mother Nature, Mother Earth?

RAY GARDNER I would say that the Chinook beliefs are very close to the other tribal governments I talk to. We all go back to the Story of Creation: when were we brought here, why were we brought here, what were we honored to be part of and what we were tasked to take care of. Those things, our culture in and of itself, tell us to do whatever we can to protect these rivers.

NWNL It’s a strong message.

RAY GARDNER It’s very deeply ingrained in all Native people. For me, coming to this cove reinforces that responsibility every time I’m here. I’ve sat through an entire tide change several times. I come at low tide; wait for the tide to come in; and wait for the tide to go back out. It’s amazing what goes on right here that is a problem. Just as we’ve sat here, I’ve watched soda-pop cans float in with the tide.

By educating the public and setting better practices, we can help. As we’ve learned more ways to do so from different organizations, we’re planning some river cleanups in our area. Many of our people will come down to this cove with me, especially at low tide, to pick up whatever debris has been left behind.

It’s frustrating to come down here on a given day; clean up every piece of debris and garbage; and return after the next tide change to find just as much or more, in an area as small as this is. Take this and magnify it by the length of the Columbia River and you can get a grasp of the problem.

NWNL I feel we all owe you, the Chinook tribe, and all tribes in the Pacific Northwest a debt of gratitude for expressing your thoughts, being responsible to Mother Nature, and sharing your work to encourage more environmental protection. I thank you for all of us. You’re giving all who live on this continent now, from many parts of the world, a gift that will benefit us all. I hope we can all jump on the bandwagon with you.

RAY GARDNER Well, I want to express my thanks because it’s people like you coming out to let the public know the issues we face. They’re real; but also, there are solutions. It’s you and organizations like American Rivers that are helping to get our rivers back into shape. For the tribal people, it warms our hearts to know that there are people trying to help us do what we know needs to be done. So, thank you!

NWNL I am excited to be mirroring your efforts and concerns.

NWNL To wrap up our conversation, how do you see assess the current strength and power of your culture in the scope of history.

RAY GARDNER I think much of what’s helped strengthen us today has been educating our tribes. It’s been difficult for us to not be able to work in today’s changed climates. It’s also very frustrating dealing with state agencies, the governor’s office and even with some federal agencies. We’re working to correct the mindset they still have that we’re working to correct. When our tribal governments visit them, it’s clear they think they’re dealing with un-educated people.

I know. I was in a meeting not long ago in the governor’s office and I actually had to stop them. And my point to them was and in the comment that I made was, when are they going to realize that they’re dealing with educated people, that they’re dealing with governments that are just as solvent if not more than their own? I think for the government systems, I think they’re starting to realize that and I think that the more they become in tune with that, the more they’re going to acknowledge the tribes and they’re going to become more effective in working with the tribes which, in the end result, constitutes the tribes having more ability to protect the river systems.

NWNL Can you describe the role river systems play in your culture?

RAY GARDNER The rivers, have everything to do with Mother Earth. As the tribes gaining education, they’re getting into all aspects of cleaning the rivers systems up, keeping the rivers healthy. They’re looking at forest land practices. They’re looking at how can they get yields of timber out of the forestland without destroying the land, the aquifers or the small streams in those ecosystems. They’re looking at how can they better keep vegetation in places where it needs to be and make sure it’s not being taken out. They’re looking at how can vegetation enhance, not only the quality of the river, but also the runs of the fish.

Some of the examples that they have of that is some of the tribes are starting to use willow and they’re planting willow trees alongside the riverbanks because they grow fast, they provide a lot of shade. So, they’re cooling the rivers down by the spawning areas and they’re already starting see a better return of fish in those areas.

So, the tribes of today are not the tribes of our forefathers. We’re a group of people that are educated in every aspect of what goes on. We’re educated in marine biology, we’re educated in forestry, we’re educated in law. We’re educated in everything that anyone else is and have attended most of the universities that everyone else has in the United States. I see that our continuing growth in education is very important to the tribes. They’re promoting it very heavily.

By comparison to other tribes our means are very small; but still, in the last 5 years, we’ve given out $260,000 in scholarships to help many of our tribal youth get an education that they would not have gotten without those scholarships. So, we’re seeing the importance of getting our people educated in all those fields. Doing that will help the entire planet when it’s all done, because they are literally thousands of years of the spirits of our ancestors that are here.

Posted by NWNL on March 21, 2024.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.