Bongos Save Forests

Mara River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Mara River Basin

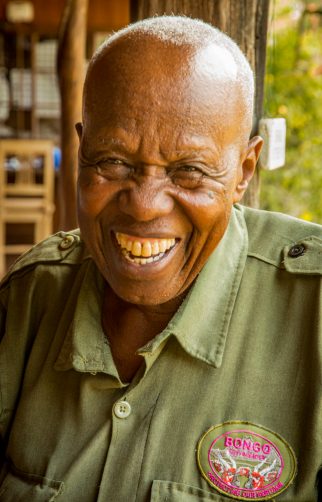

Mike Prettejohn

Founder of The Bongo Surveillance Project

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director and Photographer

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

In Kenya, growing populations’ need for land threaten natural resources. Short-term versus long-term needs play out as Kenyans create farms where there are forests. But today’s more intense droughts and increasingly scarce rainfall highlight how critical forests are in providing, moderating and preserving water supplies. If the forests go, Kenya’s thirst will grow. This dilemma is very obvious in Kenya’s Mara River Basin downstream of the Mau Forest, its headwaters.

Many are working to protect Kenya’s forest reserves. Mike Prettejohn, founder of The Bongo Surveillance Project, believes that saving mountain bongo, the largest forest antelope, will help save the forests. The world’s 120 bongo remaining in the wild are a handsome species facing extinction due to loss of safe habitat. Mike’s efforts to save bongo will save Kenya’s forests by saving bongos’ endemic habitat. Forests can be replaced (with great effort) – but an extinct species cannot. Saving the bongo is a win-win, as it will also save Kenya’s forest – and thus its water supply. No Forest-No Bongo-No Water.

NWNL Mike Prettejohn, it’s greet to meet you here at Sangare Hills, between Mt. Kenya and The Aberdare Forest. For years you’ve studied and tried to save the mountain bongo, endemic to Kenya’s highland, water-tower forests. Your struggle to raise awareness has been unusually challenging since bongo are rarely seen. What are they like and why are they special?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN East Africa bongo are the second-biggest antelope, next to the eland. They are very beautiful: dark-chestnut with white stripes, many patterns on its ears, and beautiful ivory-tipped horns. When wet with rain, their red color sort of seeps out and covers part of their stripes, helping their forest camouflage.

NWNL Tell us about bongo habitats and behavioral patterns?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN They live in big forests at an altitude of 8,000 to 10,000 feet, amongst cedars, polycarpus, olives, bamboo and other trees, surrounded by stinging nettles and broad-leaf plants. Podocarpus, cedar and bamboo forests also include open glades and watery swamps. The Aberdares, Mt Kenya, the Mau Forest and Eburu Forest all provide these same forest habitats.

Thanks to camera-trap videos, we know how bongo feed and what they eat. They’re very delicate feeders, mainly of leaves in heavy, thick forests. They eat 75% of their food by browsing; and they eat dead wood with moss on fallen trees. If moss is high, they’ll stand on their hind legs to reach it.

NWNL How do you identify the individual bongos?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN Their 12 to 13 distinct stripes create different patterns on either side of the body. Thus we must identify both sides. Facial markings are also very important for identification, as are torn ears and horn patterns. The horns of some females cross at the top, so they’re easier to identify. Also, bongo can have identifying scars from fighting with other males or other animals – maybe leopard.

For many years, people in the U.K., including Peter Comport at Aspinall Foundation, have studied bongo in zoos for many years and identify their age by horn growth of males and females. But that growth is not quite the same in zoos as it is in the wild. So far, in the wild, we use photos to follow horn growth from birth to 4-year-olds, but that takes lots of time. A computerized version would be much easier.

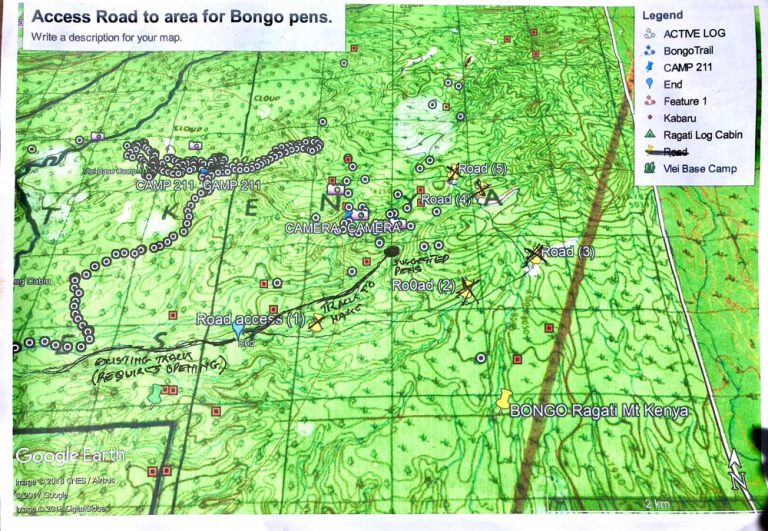

NWNL Computers, GPS, spreadsheets are all wonderful 21st-century tools for conservation. But you also have old maps here on the table. How do they help?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN This map shows next month’s reconnaissance safari route by the Bongo Surveillance Project [BSP] – which I founded and direct. This safari will use four groups in the southwest Mau Forest with KWS (Kenya Wildlife Services) and KFS (Kenya Forest Services). Our goal is to see whether the elephant and the bongo can migrate safely through.

L-R: Antique Maps of Kenya Forests & Mau Forest, courtesy A. Nightingale

It will begin in Bosta, near Kenya’s “Tea Zone.” The trek will continue across the Trans Mara section of the Mau Forest, and then through a tight 2-km- wide corridor. Then we’ll go down to Narok, on the edge of the Maasai Mara National Reserve. The distance is about 64 or 65 kilometers, in a straight line.

NWNL Who is organizing this and for what purpose?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN BSP and Mark Goss (CEO of Mara Elephant Project) are involved. BSP has been searching for bongo in the Southwest Mau for about 5 years. We monitor the area with cameras every fortnight.

There were quite a few bongo in that area when we started. It was the 2nd-biggest bongo herd in Kenya, about 25-30 animals. Then they suddenly disappeared. We know some are dead, but where are the rest? Did they migrate to the Maasai Mau Forest – a safe area of forest protected by the community and school kids – or did they also die?

NWNL What’s involved in your monitoring process?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN We identify the bongo using body markings captured in photographs taken for years to study the herd’s makeup. We know there are many calves, so the herd is doing well. But the forest is not a Reserve: it is Trust Land, thus protection is really up to the community. As the bongo and the yellow-backed duiker are very rare species, we want to create a specific protection zone. Kenya’s Government and Rhino Ark are working on that at the moment.

To go back to our upcoming reconnaissance trip, our main worry is a 2-km corridor in the middle with a road that goes through it. It’s the divide between the Sondu River, and the southern Ewaso Ng’iro River that flows to Lake Natron on the Kenya-Tanzania border.

NWNL Does that small corridor lie between the Mau’s Trans Mara and Maasai Mau Forests?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN Yes. The Mau Forest was one piece at one time. But there have been huge intrusions by developers and timber companies, especially in the Trans Mara section and in the corridor I mentioned. So, there we do surveillance by helicopter.

NWNL What are the goals of this trek?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN The team will monitor and note any signs of bongo they find. Then we will further track of those bongo – if there are any – to see where the herd is centered, if they’re just on the move. or if they’re trying to find the other group in the Southwest Mau.

NWNL Where do you get your funding?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN In the South West Mau, our permanent-basin funds come from the Dutch Government and Finlay’s Tea Estates. We have a KSh 500,000 advance (almost $US 1000) from Rhino Ark; and we’re waiting for other funding. Since we want to have permanent teams in the Trans Mara Forest, we’ve applied for US$ 50,000 from National Geographic.

NWNL Mike, where did you interest in the bongo come from?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN When I was a professional hunter, I lived near mountains where bongo still existed in the wild, and it was the most difficult animal to get.

In 1960, the government issued 20 bongo licenses, but only 2 bongos were captured. That shows the difficulty of actually finding these animals, even then. I was one of the main hunters for people wanting to find bongo. It was the ultimate thrill. One might be out for weeks and weeks and many safaris before finding a bongo. It was always a challenge.

Hunting ended in Kenya in 1963. In 2004 the Aberdares warden asked me what had happened to our bongo and whether I thought they’d become extinct. I responded, “I doubt they are extinct. But these days, with no hunting, nobody knows. Except for poachers, people rarely traverse the whole forest.”

I told the warden, “Unless you can arrange porters and food so people can spend up to 2-3 weeks at a time in the forest, you won’t find the bongo.” He asked if I would be prepared to do it if they found the money. I said I’d have a go at it. I gathered a team of people who knew the forest, and, sure enough, we found some bongo left in the wild.

NWNL Who was on the search team? Were any local forest dwellers?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN They were local poachers. The main man was Peter Mwangi Kariuki. In the 1970’s, he was employed by most of the zoos interested in bongo. They paid a lot of money to capture bongo. Peter, with others he knew, caught bongo by digging and covering pits along forested trails. Once bongo fell into a pit, the trappers fed them water and food while building a ramp from the pit to a surrounding boma, or corral. From the boma, the bongo were crated and carried out of the forest, often using up to 30 people. Most were sent to zoos. Nobody knows how many were taken, nor the huge number of those who died.

Over ten years I think Peter delivered 60 bongo to Don Hunt, who owned the Mt. Kenya Game Ranch. Many others were exported to zoos all over the world. Then it was suddenly stopped. Today, Don Hunt in Nanyuki has the only remaining bongos in captivity in Kenya – their home country. Our policy now is to get as many of those 62 exported bongos as possible back to their habitats.

NWNL How did you leap from wondering whether bongo had become extinct to creating a bongo-tracking team today with Peter Kuriuki and returning captive bongo to the wild?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN When I was asked to find out about the bongo, we began the BSP. I have managed the project from the beginning and still organize rangers on a permanent monthly basis. I get funding grants as best as I can. But I’m now coming up on 86. Some feel I should retire, but there’s no one else who will do it for nothing. No grant is for certain, and so it’s very hard to get guaranteed salaries for a Director. So, I’m here for the time being.

NWNL Where do the BSP rangers work?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN On Mt. Kenya, they work in the Ragati Conservancy. We were about to give up Ragati, until suddenly we got new pictures of bongo there. Now Ragati ia one of BSP’s most important areas.

The rangers have also started investigating Embu, a forest on the western side that was one of the biggest bongo habitats. I used to hunt and see bongo there. Embu was known as the bongo area; however there are no bongo left in Embu.

We did 2-3 years of solid work on the Embu side, but it has too much forest intrusion by people illegally living in the forest, similar to the Mau. However, more work is being done in the Mau to clear and restore the forest by moving the illegal people out, than in Embu. When fencing of Mount Kenya is complete, Embu could be restored. Then BSP could put Embu back on the list for bongo returns. Their habitat and food is still there.

NWNL Do your BSP rangers work in the Aberdares Forests as well?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN Our rangers do the odd trip in the north Aberdares, but mostly they’re in the Salient and the south Aberdares.

NWNL What are bongo conditions in the Mau Forest Complex?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN Londiani Crater, a part of the Greater Mau Forest, very recently had bongo and could again. Bongo were first discovered in Londiani, about 1900 or 1902. I have a copy of the original archives on that in London. There’s water down there and food. Since it is in a crater, that forest could be really well protected. We saw signs of bongo in there until about two years ago.

NWNL Do you think fencing could protect bongo in the Mau Forest Complex?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN Sections of Lembus Forest in the Eastern Mau could be fenced, and there’s also the Mau Summit.

NWNL Where will you find bongo to reintroduce to these forests?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN Well, there are about 700 in America and probably 500 in Europe, so the stock exists, but they first need a breeding ground here. As well, South Africans have done embryo transplants, so we could collect the bongo embryos. Dr. Morely, from Back to Africa, reckons he could produce 50 bongo calves a year, by segregating embryos from bongo cows and planting them in eland. He’s done it with cattle, so it seems he could do it with bongo, or anything else. However, people like Paul Reillo, Rare Species Conservatory Foundation and bongo owner in Florida, want nothing to do with it.

NWNL Will American or European bongo owners return their bongo?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN They all want to. They realize that bongo will be extinct in the wild in their homeland, so they’re all keen to get them back and re-established.

NWNL How can you prepare a safe habitat for their return?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN We must safeguard them from illegal forest squatters who cut trees and hunt with dogs. They kill buffalo and everything else they can, using 15 or 20 dogs. Bongo “bay up” easily and then can’t escape the dogs; so then hunters come in and spear them.

Also, as long as people with cattle are in the forest, any bongo there will be threatened. Illegally grazing cattle carry rinderpest and tick-borne diseases that can be transferred to bongo. All such illegal activities and poaching in the Protected Areas must be stopped before any bongo are introduced, because they need to be absolutely free to be able to breed.

Illegal squatters now living and farming in the Mau Forest

If squatters and hunters force bongo to break up into small herds, bongo then become easy prey to leopard, lion and hyena. A herd of 15- 20 bongo is about the minimum for breeding cycles to continue. Without breeding, a herd will die out.

NWNL How do you decide when and how to release bongo to the wild?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN It is important to have a bongo’s DNA, but it’s been very hard to get. New equipment from Sweden’s Uppsala University and the U.S. has let us identify bongo DNA. I’ve hoped this DNA could indicate males and females in a group, and the relations between then. They say it can be done but needs a lot more work.

They also advised us not to reintroduce captive animals back into different places than from where they were taken. For example, most captive bongo came from the Aberdares, so putting them back to the Mau Forest or Mt. Kenya would be fine. So, that’s how we’ll start.

NWNL Prior to release, what measures can be taken to ensure their likelihood of survival?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN

We must check disease factors. Animals bred in zoos for years are very prone to tickborne diseases, rinderpest and other things we have here. So, we darted and captured bushbuck from potential bongo areas to assess the immunities bongo will need. We’ve already dealt with 17 of those 62 captive bongos. They were already immune or have been covered for those diseases brought in by cattle.

A total screening has not been done yet, because we don’t have that equipment. But South Africa is happy to let Kenyan vets use their equipment before any bongos are put back to the wild. That will allow our bongo to be covered as near as possible for cattle diseases.

NWNL Once the captive bongo are healthy, how will you reintroduce them to the forest?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN We’ll first build pens to acclimatize bongo to the forest. It’s not been done yet for bongo; but South Africa, having rewilded sable and roan antelope, has given us their plans for pre-release pens. They are roughly 20-acre paddocks with “crushes” for inoculation, and so on. We’ll start by placing 6-8 males and females – a group big enough for breeding – into a pen with pellets of alfalfa and other food they eat when in the wild. In about six weeks, we’ll open the doors. They’ll probably come back to be fed, and then eventually disappear.

NWNL You say that before heavy human settlement, bongo migrated between the now-separate “forest islands” of the Aberdare, Mau, Eburu and Mt Kenya Forests. How would you describe those separated forests becoming hospitable bongo habitat today?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN We’ve monitored areas since 2003, and are now concentrating on where we’re pretty sure there are herds left. The groups we’ve found in the last 20 years are broken up, due to human intrusion. The southern Aberdare bongo are pretty well gone. The northern Aberdare bongo have just recently disappeared. Either they died or moved into the protected area of the Salient, a lower-altitude extension of the forest.

The Salient has been protected over the last 60 or 70 years as a Forest Reserve, thanks to presence of Treetops Lodge [now within 2,500 acres of native forest]. Otherwise, it too would have degraded into “human habitat.” The Salient now has the biggest herd in the wild, with many young coming up, thanks to BSP rangers and recent Kenya Wildlife Service improvements!

NWNL How will you transport bongo into these dense forests? We drove into Ragati Conservancy via a rocky, narrow, winding track, dodging many trees and rocks. How are you going to take bongo in a crate up a road like that?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN It’s quite expensive transporting captive bongo into these forests. The only way is by the big British Army helicopters and some privately-owned copters. Christian Lambrechts, with Rhino Ark, has talked to the British Army about helping with our bongo work. They can’t fly civilians, but they can do food drops or bongo drops. Such drops were quite successful in moving Kenya’s endangered hirola antelope from the Tana region into a safer area.

NWNL Since NWNL specifically studies the Mara River, I’m particularly interested in the possibility of bongo there.

MIKE PRETTEJOHN There were many bongo there, but now they’re only in the Southwest Mau, since it’s protected by big tea estates that create a buffer between towns and the forest. They minimize the intrusion into the Southwest Mau.

Thus, within the last few years, we’ve detected a reasonably-sized herd in the Maasai Mau’s “Trust Land,” which we’re trying to make a “Forest Reserve” for the safety of the bongo and rare yellow-backed duiker antelopes. But added protection is needed, since the past 4 -5 years has seen large intrusions from huge communities on the forest’s edge. It’s been very difficult to stop them from taking cattle in there.

Human incursion has degraded the Mau Forest, however the presence of bright green tea fields (Bottom R) has prevented illegal settlement and deforestation on the western border of the Mau.

NWNL What about Eburu Forest, seemingly separate from the Mau Forest?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN Eburu’s recent settlement is isolated from the Mau Forest Complex. It is typical bongo forest. Bongo have always been there – but that was little known. When we started monitoring wild bongo areas, Eburu was our first choice for their reintroduction, because it is ring-fenced and accessible. Our photographs first showed probably six or so bongo. But for the last two years, we only have pictures of two males. So, it is critical to get more bongo back in there.

Before Eburu’s fencing, there were human intrusions, droughts and many Maasai cattle pushing in. Now huge populations surround the forest. Despite fencing, their entry seems to be unstoppable. I think money passes hands, allowing them through. Thus, cattle from as far as Kajiado and Narok have brought disease into the forest. Until that’s cleared up, we feel Ragati is the prime place to start this reintroduction experiment.

NWNL That is a sad commentary on the effectiveness of fencing.

MIKE PRETTEJOHN

Yes. The Eburu fence is great, but not 100% secure. The forest’s safety depends how the fence is monitored, because it can be and is shorted. People put a stick between wires, roll themselves in cardboard and creep under the fence – with their dogs. There are eight gates which must all be monitored by KFS personnel who are not corruptible. I now hear all new KFS monitors are coming into Eburu, – and hopefully will be beyond corruption.

NWNL So although not fenced, is Ragati is safer for bongo than Eburu with its human, cattle and dogs?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN The fencing at Ragati is being built now. The whole of Mt. Kenya, like the whole of Aberdares, is in the process of being fenced by Rhino Ark. Because of our bongo going in, they are working on that fencing right now.

NWNL Is there less human settlement around Ragati than Eburru?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN There’s a lot around both, but Ragati’s forest is much more extensive than Eburu’s – with fewer tracks and roads. There are plenty of cattle in the lower forest of Ragati, but the area we’ve chosen for the bongo is beyond their reach.

NWNL What steps remain to move bongo into Ragati?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN It will be a KWS Board-approved process, yet its timing is unknown. We’ll present an application to KWS, with our program and Malte Sommerlatte’s paper. The plan has the backing of the Mountain Director, the forest people, Ragati Conservancy and BSP. So, if KWS accepts our application, we hope to begin in 2-3 months. We must. Otherwise, that one remaining bongo in Ragati will be gone. We will see if the wild and captive can mix; how they get together; and how quickly they take to breed again.

NWNL Are there any other areas where there are bongo?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN There used to be manyin the Cherangani Hills, but they’re gone, as are all bongo in central Mau, the Lembus Forest (still one of the best forests in the Mau) and the Mau Summit. Today in the Mau, bongo are now only in the Southwest Mau, and probably Trans Mara and Maasai Mau Forest.

NWNL Can the presence of bongo protect and ensure the future of the Mau Forest – and thus the Mara River? Could fencing the Mau’s remaining forest on ever bring in tourism focused on bongos, yellow-backed duiker, fishing and forest ecology?

Finlay Tea Company’s Fishing Camp in the old-growth Western Mau Forest, with Simon Maturi

MIKE PRETTEJOHN There is virtually no tourism in the Mau Forest today, except a bit of fishing around the tea estates, like Finlay’s Fishing Camp. The only tourism in the Kenya’s Mara River Basin is on its plains, full of wildebeest and zebra migrations and big, iconic animals. I don’t know why nobody’s put a Treetops-style lodge in the Mau Forest.

NWNL If bongo and yellow-backed duiker were there, would such a lodge succeed?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN Absolutely. I’ve suggested to several people in tourism in the Maasai Mara, they should move into the forest. Yet no exciting masses of animals are there at the moment. But when bongo are established and can be seen, I think people will come.

NWNL People fly to Rwanda or Uganda – at great cost – to see a gorilla for just one hour, so wouldn’t they go just a short distance from the Maasai Mara to see bongo and duiker?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN Well, those countries can guarantee their seeing gorillas, but at the moment we can’t guarantee seeing bongo. And would bongo have the same appeal as gorillas, which are like us in a way?

NWNL But bongo have the cachet of being almost-extinct with just 120 left. People are fascinated by the rare and unusual.

MIKE PRETTEJOHN Well, we first need to teach and excite people about these little-known bongo….

NWNL Ah as BSP Founder, that’s your job – and we want to support you!

NWNL Your brochure covers educating the youth, creating tree nurseries and sponsoring bongo wildlife clubs. Is this how bongo protection will evolve and grow?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN Well, I think we should educate and get involved with local, young people and their communities. BSP now has 19 Bongo Clubs, founded by Juliette Shears, BSP volunteer and fundraiser and managed by Peter Munene Mutongu. With 40 members in each club, plus all our trekkers, BSP probably reaches about 10,000 people who hear about the bongo.

NWNL Where are those 19 BSP schools?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN They are mostly in the Mau’s Southwest Mau, Maasai Mau, and Eburu Forests. We also have some in the Aberdares and on Mt. Kenya. All have new kids coming in every year.

BSP also takes its Bongo Club groups to parks and other parts of the country and on day trips and with a bit of camping experience in the Naro Moru camping ground. At the William Holden Education Center, they see bongo and hear lectures on the environment, saving wood, saving fuels and using solar energy.

We’ve done 1 or 2 big solar schemes for homes without electricity, so students can work at night. Those students have done particularly well in their education because for only 800 shillings [US $8],they can use their portable solar lamps to work at night.

NWNL Do your schools focus on bongo habitat as well as forest protection?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN They teach reforestation and use of alternative fuels to stop them from cutting wood. We also have very popular programs for replanting indigenous trees. Every school has a tree nursery that comes from Finlay’s Tea. The children sell the trees to parents and other people, and use our schools for their reforestation activities.

NWNL Did BSP start these schools?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN No, but BSP started their Forestry sections and training.

NWNL Clearly, saving the bongo is your passion, Mike. Yet you struggle to raise money and support for an unknown species. What is the best way to make this invisible animal more visible and more beloved?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN Once we get bongo moved back into the forest, people will be able to see them — and that will draw more people. Ragati already has a platform near a saltlick where people can spend the evening with a spotlight to watch them. Bongo are curious. They were regular visitors to the Ark, a lodge similar to Treetops, until they disappeared in 1988.

NWNL So you feel you can make the elusive bongo visible?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN Definitely. I think soon more and more bongo will be seen out in the open in the Aberdares,. Tourists driving around now are seeing them again! This hasn’t happened for a long time. They’re now more habituated and are breeding well. We may see one tonight driving to the Aberdares’ Rhino Retreat.

NWNL How do you define the significance of your quest?

MIKE PRETTEJOHN I think that is critical to talk about vulnerable, iconic species. BSP got the Aberdare National Park to register bongo as the “Flagship of the Forest.” BSP and Ragati use the bongo as their emblem. It would be great if we could have somebody with a high profile, like Ian McCallum, speak at our schools and show film documentaries on how the waters of Mt. Kenya drain downstream into the Tana. That way students could connect their forest with their water resources and their charismatic species.

NWNL Mike, here’s to your success – and to tourists of the future enjoying bongo in Kenya’s forests. Thank you so very much.

Posted by NWNL on July 21, 2020.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.