Canada’s Columbia Basin Trust

Columbia River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Columbia River Basin

Kindy Gosal

Columbia Basin Trust Board of Directors

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Director & Photographer

Robin MacEwan

NWNL Advisor on Natural Resource Management

This extensive interview offers a well-informed background on U.S/Canadian dams built under the Columbia Dam Treat and the ongoing consequences in Canada. Kindy is a Professional Forester by training and calls himself a “ community practitioner.” An active member of the British Columbia’s Columbia Basin Trust board, Kindy met us at Canal Flats, the Columbia River headwaters, to discuss the fraught history of giant hydropower and storage dams. He also reviewed issues that will affect whether the US and Canada renew, renegotiate or terminate their Columbia Dam Treaty in 2024.

COLUMBIA RIVER BASIN WATER ISSUES

DAMS STOPPED THE SALMON

DAM IMPACTS in CANADA

COMMUNITIES & ENGINEERS

TRANS-BOUNDARY TREATY PARTNERS

GRASSROOTS STEWARDSHIP

A MODEL of COMMUNITY-BASED POWER

POTENTIAL POWER OF EDUCATION

CLIMATE CHANGE

All images © Alison M Jones unless otherwise credited. All rights reserved.

NWNL Thank you, Kindy, for your time. We, with No Water No Life, are intrigued with your Columbia Basin Trust model that works so closely with your communities to support their health and well-being. We all struggle against local impacts from dams, climate change and various watershed threats, but what particular issues are challenging British Columbia today that concern you and your neighbors who live in this lovely mountainous headwaters region of the Upper Columbia River?

KINDY GOSAL Population growth has been growing for a long, long time. Ours in British Columbia hasn’t been huge for the last few decades, but we’re just starting to have large amounts of development happening in our area. We’ve never had to face these realities. This falls on the shoulders of regional governments, but they haven’t dealt too much with this before. They’re reacting to the best of their ability, but need additional capacity, information and resources to deal with these issues. Thus, the role of our organization – Columbia Basin Trust (hereafter CBT) –- is to be adaptive to what’s happening around us.

I give the regional governments accolades for dealing with these issues. As the rubber hits the road in the communities here, our local leaders are taking charge and dealing with these issues. For everyone who is not proactive, there are two or three that are very proactive in these issues.

The problem is we haven’t had experience in dealing with these issues. So, they may seem slow to move up the mark; but we are moving. You just visited Lake Windemere, and heard about their growth issues around Columbia Lake. Local grassroot processes here are now starting to deal with these issues.

NWNL We went out on Lake Windemere yesterday with Heather Leschied with Wildsight. As we circled the lake, we saw the issues of second homes used only part time. That community is finding it hard to gather their support.

KINDY GOSAL Well, I have a second home in a distant location on the coast, and so I know what it’s like. I’m committed in a certain way because I moved there for the beauty of it and now want to help retain that. New people are coming and there will probably be more. We need to work with them and engage them.

We probably can learn much from other jurisdictions. Sometimes it seems we’re the bleeding edge, but obviously other communities and jurisdictions have gone through issues now facing the Columbia Basin Trust [hereafter, CBT]. We should draw on external expertise. The best solutions are grassroot solutions, but we can also learn from other jurisdictions.

NWNL Your comments remind me of the community-based conservation approach I’ve been involved with in Kenya. Grassroots and community inclusion of people, farmers, ranchers, pastoralists, fishers and others create a unity and education around local issues. Such principles vary for each jurisdiction. I’ve already seen that each local community here has its own character, history and leaders. We are all fiercely independent in many ways – which is good!

Is that a good segue to talking about your Columbia Basin Management Plan?

KINDY GOSAL Yes! The Columbia Basin Trust was created by a Provincial Legislative Act in 1995. This Act put forward that the people of the Columbia Basin were not adequately consulted during construction of the Columbia River Treaty Dams and that we were negatively impacted. That Act also came with an endowment in recognition of the dams’ negative impacts.

Let me go back to the transboundary U.S.-Canada Columbia River Basin around the early 1990’s. There was massive growth then in the U.S. and in our region. We all needed additional energy to meet industrial and community demands. If you look at these mountains, especially now, the amount of snow is striking. These huge water towers are the northern reaches of the Columbia Basin’s snow catchment. So, from an engineering perspective, the Columbia is a very dynamic system. These water towers melt in the spring, creating a huge freshet event that puts a large amount of water into the system as it heads downstream and floods some of the growing communities in both Canada and the U.S.

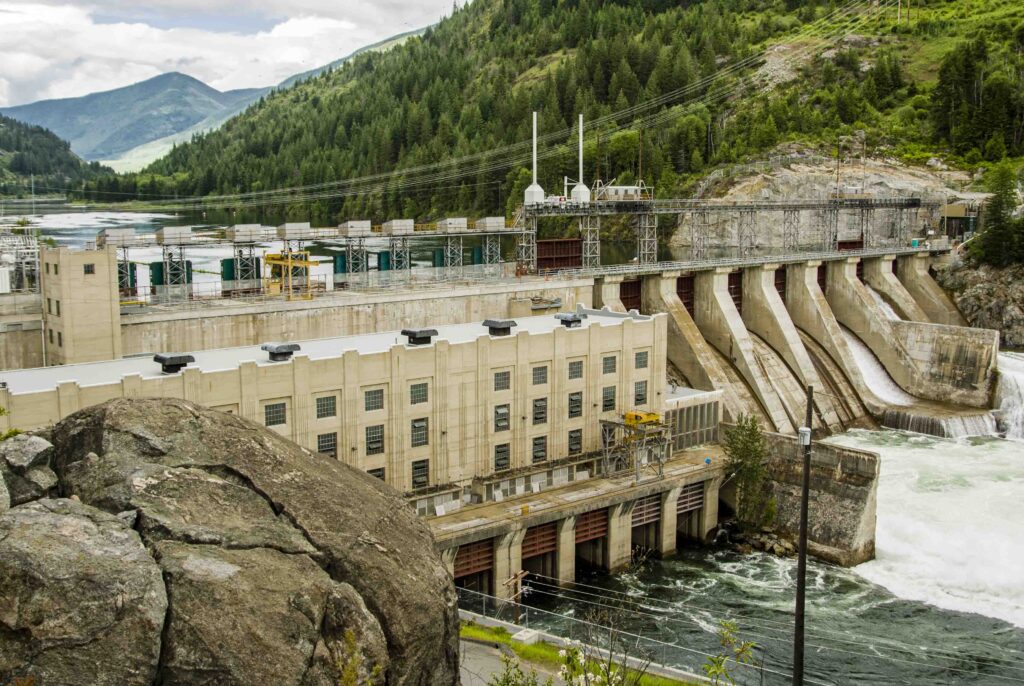

There’s a lot of draw of headwaters from here to Astoria, Oregon – a vertical drop of 2,650 feet, I believe, creating a huge potential for hydroelectric energy. Engineers looked at the Columbia River one way; and community planners and politicians saw the Columbia as a flood risk.

As populations and industry grew, there was a growing cry to tame the wild river. We saw hydroelectricity develop in the U.S. in the 20’s and 30’s. In 1935, a massive event happened – from our perspective in Canada.

Prior to 1935, the Columbia was a very dynamic ecosystem, with a huge amount of wildlife – 700 species of reptiles and mammals! One of the most unique features was our salmon. We had some of the largest salmon runs in North America. But in building the Grand Coulee Dam in 1935, the U.S. blocked salmon runs into northern Canada. During construction of the Grand Coulee, despite Canadian provincial and federal representatives, no considerations were made to the impending impacts to migratory fish – except for a gentleman from Nelson Rod and Gun Club. He said, “If you build a dam on the Columbia, you are probably going to impact those migratory fish that come up here.”

Well, they built the Grand Coulee, and suddenly those salmon runs stopped. That was a massive ecosystem event. The young fish go from here to the ocean where they harvest the ocean’s riches. Then they make their way back up here, die after spawning and their carcasses, full of ocean nutrients, feed a whole ecosystem here in the Columbia system. For millenia, all the bears and birds here relied on that nutrition, as well as First Nations and settlers here in the 1930’s. Those communities depended on the salmon for nutrition. But there were none after construction of the Grand Coulee Dam.

The Grand Coulee Dam construction started in 1935 cutting off the salmon; but the damming impacts didn’t stop there. With growing communities, there were greater cries in the U.S. and Canada for more flood control. Flood events continued; and as populations grew, people needed more hydroelectric energy. Then, a 1948 flood in Van Port, Oregon killed people and destroyed the town. U.S. and Canada officials began to negotiate a bi-national treaty to optimize power generated by the Columbia River and to create flood control.

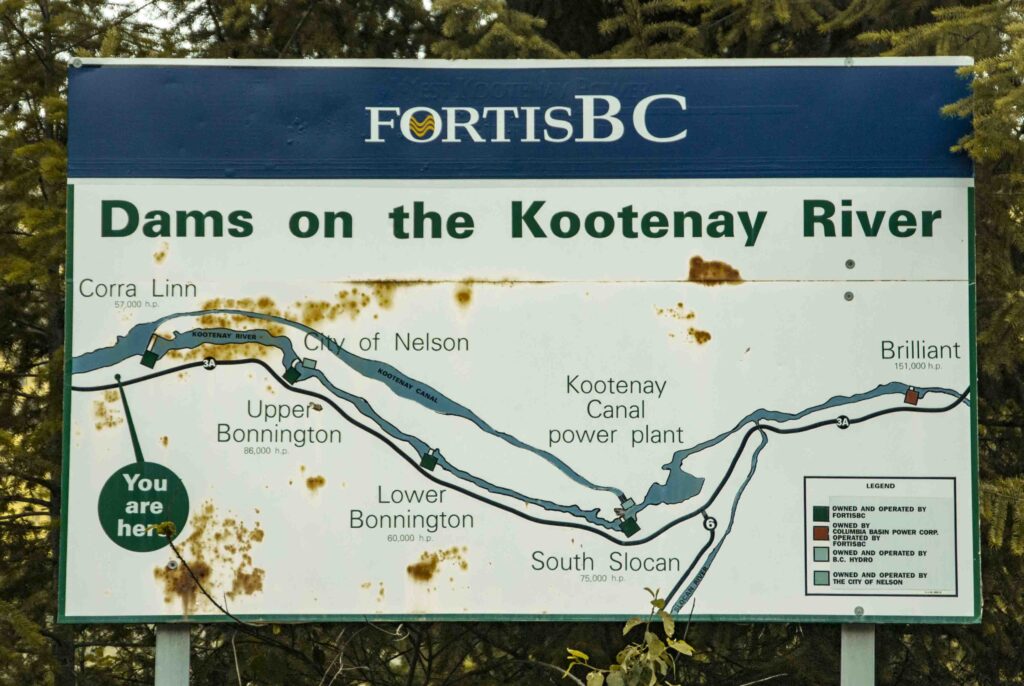

In 1964, the U.S. and Canada agreed on location for storage dams in Canada, set and ratified the Columbia River Treaty. Canada agreed to create 3 major storage reservoirs: Mica Dam north of Revelstoke; Keenleyside Dam in Castlegar; and Duncan Dam in the north end of Kootenay Lake.

Canada’s storage of a huge amount of water for power and flood control primarily benefitted existing U.S. facilities. As designed, these dams did not generate power until later. Mica Dam had power generation in its design, but Keenleyside and Duncan were just storage reservoirs. Negotiations with the U.S. over building these dams also included constructing Libby Dam to prevent Kootenay River floodwaters from reaching Libby, Montana, by holding them in Lake Koocanusa, built on the U.S.-Canada border.

Regarding these dams, people here will tell you they were not adequately consulted. In fact, there was almost no consultation on possible impacts regarding the loss of low-elevation land. In the entire 2,000 km of the Columbia River, from Canal Flats headwaters to Astoria, the only section still in its original state is the 200 km from the headwaters here to the top of Kinbasket Reservoir, north of Golden.

There are over 450 dams on the Columbia – making it one of the most dammed river systems in the world. Our 200-km Columbia Wetlands [a Ramsar Wetlands of International Importance] indicates what our prime agricultural and forestry lands were like before being flooded behind dams. That’s where communities wanted to locate. That’s where their recreation took place. That’s what was taken away from us.

That drastically altered how people live here. We were promised that we’d have recreational lakes and communities would be built around these lakes. They said we’d have efficient transportation infrastructure around the lakes and much more industry due to electricity. None of those promises held true.

We now have industrial-sized reservoirs. Kinbasket Reservoir has an elevation range of 155 vertical feet. For much of the year, the Columbia River runs through the middle of the reservoir with 5 kms of mud flats on either side. In 1968 they built Duncan Dam; in 1969 they built Keenleyside; and in 1972 they completed Mica Dam. Then they filled these dams.

It wasn’t until they cleared the reservoirs and relocated our communities before flooding the land, that people realized what was about to happen. The key problem for those of us who grew up and have children here is that we weren’t involved in the decisions made in Victoria, Washington and Ottawa. Now, we and our children must live with those decisions.

Our economies are constrained by that past. So, in recognition of that, leaders from this region met with our provincial government in 1995. They negotiated a deal recognizing these negative impacts and created a Trust with people of this region to build better social, economic and environmental lives for them. That’s the Columbia Basin Trust [CBT].

We committed CBT to be a grassroots organization. In partnership with the province, we received an endowment of money and a cost-sharing agreement to address the dam’s negative legacy (per the perspective of people here) by building a positive legacy through reinvesting money created by some of the dams’ hydroelectric generation.

With that money, we built hydroelectric generation on Keenleyside Dam. We purchased Brilliant Dam and added generation there. We reinvested our money to be a sustainable revenue to help communities provide better social, economic and environmental wellbeing for people in this Basin. Before embarking on that, we committed to creating a Management Plan.

We consulted with thousands in the Basin, asking, “What key things do you want us to work on?” They came to symposiums with ideas that were the genesis of the Columbia Basin Management Plan – basically our “bible” in terms of activities we undertake and support.

NWNL What did you learn that helped form your Management Plan?

KINDY GOSAL Basically, people said, “Do everything.” The activities the Columbia Basin Trust offers are mind-boggling. They’re in social and environmental areas. Basin-wide, we support:

— watershed groups (like the Wildsight group you met yesterday)

–– grassroot environmental initiatives and economic development

–– arts and culture groups

— education for youth, and literacy programs for adults

— low-income housing projects for seniors

On and on and on….

Our seed money keeps them going and we give money to local governments to allocate to smaller community groups. That empowers both local governments and local communities to take ownership. Our grants now total about $5 million, and they are still growing as we put our projects online.

We all recognize this region benefits from the Columbia River Treaty Dams. As a society, we are dependent upon electricity. Furthermore, since British Columbia is a net importer for its needs, we’ll probably need to generate more. Thus, we understand the societal benefits that accrue from Columbia River Treaty dams.

Additional benefits accrue to the U.S. from our retaining spring floodwaters until winter’s demands for them to generate more electricity. There are also benefits accrued here. We now produce about a billion dollars of electricity. We built other subsidiary dams, like Revelstoke Dam, to build electricity facilities. Kootenay Canal Plant produces huge amounts of electricity for the province. Revelstoke Dam, built after the Treaty Dams, provides much-needed electricity and economic growth for the entire U.S. Pacific Northwest and British Columbia. But somebody must pay the piper. Somebody had to bear the burden – and that was us.

Looking at future opportunities in this basin, we will become more dependent on electricity in this basin, not less. That’s a big issue for us. We are an important part of the provincial economy now and work with the province and agencies like B.C. Hydro to help the province and its people along the system meet their need and properly utilize these water resources.

NWNL Is CBT’s working relationship with B.C. Hydro a good partnership?

KINDY GOSAL My working relationship and that of many others with B.C. Hydro is excellent in many ways. Their corporate mandate is very different from ours – and we respect that. Our mandate differs from theirs – and they respect that. They’ve helped us immensely in water-management issues we’ve started. They’re supportive and understand that the future of this system’s management is very complex and must involve the people now.

In the 60’s we didn’t involve the people very much. But now, public consultation is key to doing anything. They and we realize that and are working to ensure that – whatever happens in this region – the people are involved in a way that recognizes their rights, views and values.

NWNL Has that relationship with BC Hydro changed, or has it been true historically?

KINDY GOSAL It has changed. Early on, the provincial government tasked B.C. Hydro to resettle communities and negotiate with people in homes being flooded by the dams. That created a huge negative legacy. People did not feel adequately involved. They were unhappy; and B.C. Hydro bore the brunt of that.

Time goes on, attitudes change. As an organization, CBT says, “We recognize that what happened left a negative legacy; but we must build a positive future. That requires us all to work together.” While we need to recognize history, learn from it and not repeat it, we also must make sure we don’t dwell on that past negativity. I do think the region’s relationship with B.C. Hydro has improved.

KINDY GOSAL When we built the CBT Management Plan, people in the basin stressed that the Columbia River Treaty Dams were originally built without people’s knowledge, and that was how major water management decisions were made. They now want CBT to take a very strong role with a key focus to ensuring that the people are engaged and informed, since they had no information before.

“We couldn’t get any information on what was happening. We want your organization to build capacity of the people and their understanding of water issues. We want a guarantee that we’ll be involved in any major decisions regarding this basin’s future.” With those comments in mind, we looked at water and other issues across the basin, and saw we’re heavily connected with the U.S. Our water management is linked to U.S. water management and needs.

Thus, there must be trans-boundary dialogue. We’ve taken it upon ourselves to facilitate and convene dialogue with U.S. organizations on their issues, so we better understand their needs. Also, and more importantly from our perspective, it’s critical they understand our issues, needs and demands. Our people are strong, articulate, have needs and must be recognized when any big decisions happen in the future.

Currently, we’re focusing on the future of the Columbia River Treaty. It was created as an Evergreen Treaty – meaning provisions are included for its renewal, termination or renegotiation 60 years after its original 1964 signing. That means 2024 offers a chance to renew, renegotiate or terminate the treaty if either party wants to do so. A ten-years notice is needed, and the earliest that can happen is 2014. It is a pretty major piece of trans-boundary bilateral water management. Thus, from our perspective it’s incumbent on all of us to study whether the Treaty currently addresses needs of the people of the basin.

NWNL What thoughts does CBT have on a potential renegotiation?

KINDY GOSAL CBT’s role in everything is to make sure people on our basin are informed, so they can comment wisely on the treaty’s future. CBT has no organizational or advocacy mandate on the Treaty. That might seem wishy-washy, but our role is to strengthen the understanding of individuals, groups and organizations so they can articulate what they want. If we’re successful at that, our people will be able to address the powers that be and influence their decisions. Our role is to help people promote their views and values. The Treaty’s ongoing management depends on Canada’s provincial and federal governments and of U.S. federal governmental agencies.

NWNL I understand CBT is a conduit for information and resources to empower individuals and communities to research and ponder issues they may, or may not, need or want. Is CBT seen as controversial in any way?

KINDY GOSAL Sure it is. There are always controversies. For instance, should we have invested our endowment in the power of production business? Certainly not everybody agreed. And a few years ago, we thought about selling our power assets and reinvesting in other areas; but the people of the basin came out very strongly saying “No, that’s not a good idea”.

When you put money into communities, of course there is controversy. There are always folks in any community that don’t support funding for certain projects. But, at the heart of our organization, we support the people; and have no agenda. We merely support them in doing what they want to do better.

Given those concepts, there really isn’t any controversy about who we are and what we do. But there is controversy over the fine details of how that happens. We keep it that way for a reason. A negative legacy was our genesis. Our goal is to build a positive future. To do so, we support people; let them do what they want; and foster dialogues.

For instance, I’m the Manager of Water Initiatives. Whenever we have water programs, there are many divergent views. Our role isn’t to take sides or to stifle any views or anybody. We make sure all stakeholders can speak.

We first share the best information available. When we bring the right people together and empower them, they make the right decisions for their community. We include grass-root folks in our discussions, not just scientists, and not just representatives from the province or the federal government. There’s a lot of grassroots knowledge and intelligence that will help solve our major issues.

NWNL It is impressive to hear about your grass-roots philosophy. Across the globe, water issues can be acrimonious, if not openly discussed and carefully explained

KINDY GOSAL We’ve been involved in many international water forums, talking about our methodologies, perspectives, and theories on how we engage in the Columbia’s water issues. We’re not completely unique, but we are unique in that we have revenue.

Money is very powerful in its own way; but we use money to empower people, which is even more powerful. Our money builds communities and moves them towards building a better future. We’re not always successful and we have controversies. There are always debates on our methodology in putting programs in place; what we should or shouldn’t fund; and what our programs should look like. But those are relatively minor details in the grand scheme.

The grand scheme is to build a better future by empowering people. People pay a lot of lip service to that, but as CBT Staff and Board Director, I know that collectively we can get communities realizing they can make a difference. That’s powerful. That’s a challenge. We aren’t perfect. We have as many failures as we have successes; but we keep doing it.

Our Board of Directors is 12 basin residents who deeply believe in CBT concepts. They aren’t paid: so none are here for profit or money. They do this because they love their communities and want build a positive legacy for future generations.

NWNL It seems CBT has created an underlying trust in the community.

KINDY GOSAL There are some communities that, due to past issues, may hold some animosity or not completely trust us. But that doesn’t stop us. We hope to build everybody’s trust. We’ve only been here since 1995 and didn’t have much staffing or resources until 1999-2000. Only in the last 6-7 years have we had the financial capital and staffing to move out to communities.

In those six years, we started this legacy, but it will take time. One frustrating thing is there are people in the basin who don’t know about us. But that’s the way it is. Yet it’s heartwarming to overhear stories in a restaurant about something we did. That’s when we know we’re making inroads.

We’re here for the long term and not going anywhere. We are here for generations. It’s a long dance – a slow dance; and we are committed to that, and hopefully everybody will eventually believe that.

NWNL Do you know other models like CBT?

KINDY GOSAL No. We seem to have a unique three-prong approach:

NWNL Tell us about your school-based water campaign?

KINDY GOSAL Right now, we are making decisions and are in position of power, having clawed and scratched our way into senior management. Now we are people of influence in this region and we’re at the helm.

When we were 15 or 16, we derided those with their hand on the helm. At 20, we thought our destiny was to lead communities. In our 30’s, we realized the enormity of the problems. In our 40’s, we felt incapable of dealing with what was happening.

Looking back on that sequence, I realize we’re now at the helm and must make our best decisions. Most importantly, we must look at schools and those coming behind us to be sure they’re better prepared than we were to face today’s issues.

As an organization, we at CBT felt it was our responsibility to consider our best legacy and build a base of knowledge so our kids will understand these issues and have a sense of place, of what we have now, and of what happened. Then they can chart their own future without those of us who may not be as well-equipped as they to hold onto this place.

School-based education seemed to us like an obvious start – more than community education. We need children in this basin to be better prepared than we were. When they come out of school, we need them to understand what the Columbia Basin is, that we’re connected with the U.S., how water works and why it’s so important. They must be ready to deal with these things.

NWNL How you are initiating this, specifically?

KINDY GOSAL Nothing is – and everything is complicated. I work with our Water Initiatives Committee, a subsection of our Board of Directors. It includes great visionaries: Gary Merkel, our Board Chair; Josh Mancusa, former Chair; and others before them. We asked ourselves how to best work with school kids of the basin – as well as the many committed schoolteachers and people in the school system who are stressed out, under-funded and lack support.

Schools now are bulging at the seams and underfunded to prepare future generations. So, we decided to build the capacity of the educators. To help them do their jobs better and more easily, we brought environmental and school-based educators together with our network of administrators and teachers in all school districts in the basin.

We told NGOs involved in school-based education what we wanted to do; asked their help; and funded these experts. We used their wisdom to form the Columbia Basin Environmental Education Network. We provided workshops to design a school-based education program focused on water and stewardship. That is now available to all Columbia Basin schools. We supported teachers and educators to help them do their work better.

NWNL CBT funded their workshop initiatives?

KINDY GOSAL That’s correct. We were the facilitators and conveners. I can’t address these issues; but I can help facilitate and convene people smarter than me to decide what to do. We got them to the table and gave information and a little bit of financial resources. We can facilitate and convene experts, but we don’t pretend to have their knowledge or capacity.

NWNL So you facilitate, convene and fund? The last is the key, I suppose.

KINDY GOSAL Yes, the key is the financial resources behind us. To build capacity, you need money. But the other part is to fund folks outside the region to build up partnerships with universities and find a bit of seed money for grad students who can work for watershed groups.

It’s about knitting it all together: capacity, understanding, collaborations, partnerships; and then to increase influence by being a facilitator, convener and providing a little bit of money. It’s simple when put in those terms; but it’s complex too.

NWNL As an American, I hesitate to ask this next question… Was your experience working with U.S. agencies positive, negative or, at least constructive?

KINDY GOSAL It was wonderful. Working with all agencies is different. Remember, we’re all people – and wonderful people work in every agency. Nobody starts their day mulling how to do something bad in this world. I think everybody gets out of bed and says, “I’m going to do something good today.”

I believe that inherent thought is there, whether for a U.S. agency, a Canada agency in Canada, or a community group. You have to say, “Look, let’s connect, let’s talk about what you’re doing and what you’re up to. Let’s talk about what we are doing. Let’s talk about our commonalities and let’s see if we want to, or if we can, work together. Let’s figure out what our partnership is or could be.”

My experiences with U.S. agencies have been very good, including a workshop in Cranbrook just before you came. Some wonderful folks from U.S. provided us with information; plus, we had a great time. They have their mandate of what to do, their roles and their responsibilities. We don’t always agree in terms of management systems, whether it’s B.C. Hydro or the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. (When I say “we,” I mean the people in the region.)

But, at the end of the day, we collaborate and share information. Perhaps, we can get all these agencies to recognize what our people need and want. Then they can integrate that into their operations. I think that can happen if we stay positive and keep working at it. Dialogue and building partnerships are key.

NWNL Do you find there’s less concern about border issues in the U.S. — or that U.S. agencies and environmental groups you work with have less of a sense of imminent concerns?

KINDY GOSAL No. I don’t have much contact with U.S. NGOs, but I sense their urgency, especially with big issues. They have sub-base and planning processes led by the Northwest Power and Conservation Council and are hugely responsive to urgent fish and wildlife restoration needs, from what I observe.

KINDY GOSAL The key thing here about climate change is our winters are getting warmer and milder. We’ll also most probably see increases in drought and dryer summers.

Here’s the key to dealing with climate change: We can’t expect everything we’ve seen in the last 100 years to be the same for the next 100 years. “It that ain’t how the world works.” It has never worked that way before and won’t now, no matter how much we hope. It will change.

Let’s first take anthropogenic causes of climate change, human carbon emissions, etc. out of the picture. We’ve often had a fluctuating climates for this planet. We’ve had Ice Ages with hundreds of feet of ice. We’ve had tropical forests when the dinosaurs were on the earth. All these things happened. We’re now on the cusp of other change – maybe not so dramatic, maybe quite dramatic.

Then, let’s throw the anthropogenic part back in – that humans have accelerated this climate change. We’ve never seen such rapid climate changes as we’ve seen over the last 100 years, especially since industrialization. We’re sucking all the carbon that sank beneath the planet’s shell back into the atmosphere. That’s having an effect, since carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas warming the temperature.

Now, if you combine the two, it’s getting warmer. So, let’s get over it. We’re going to have to adapt. See this opposable thumb we talked about earlier? We should talk about mitigation and reducing impacts. It’s going to get warmer and so we should start dialoguing about changes we’ve seen in the past and what to expect here in the future: warmer temperatures, less low elevation snowpack as it goes up the elevation range a little more. We’ll start to see more rain on snow events – and maybe an increase in drought. All this we can kind of predict with a pretty good probability of seeing this as the future, since we’re starting to see it now. The big thing is what will we do about it.

As an organization, our big CBT message to everyone is that the future will change. We must take the science and knowledge we must ensure we use greater flexibility to build our communities and plan our infrastructure (roads, water storage, sewer, etc.) to deal with drought or increased floods. We should use adaptive pioneer approaches. Mostly, we should get on with it – not waste negative time debating what doesn’t need debating.

NWNL Do you have specific proposals at this point for this valley?

KINDY GOSAL Yes, we are working on it. The first phase is to take the best science we have on past climate changes and future models to suggest what we can expect in this valley. The next phase is to go into the communities and with hands-on, adaptation planning. Rather than us present, we’ll go into these communities with scientists who will say, “Here is what we perceive will be climate change impacts in your area. Here’s where you’re vulnerable to these impacts on transportation, water, sewer, roads, and all infrastructure. Here’s adaptation planning you should integrate into your operational plans. That tangible, on-the-ground stuff is the next phase of our work we are just embarking on. We have a group starting to work on that on Wednesday.

NWNL Do you have a sense of what the range of the proposals cover?

KINDY GOSAL Yes. I’ll use Golden as an example. We are going to look at flood frequency on some of our rivers that run through the community; at the dike infrastructure and emergency flood response plans; and at whether they are sufficiently flexible or adaptable for future flooding potential and what or where we can do something if there’s an issue.

Many have not really met their set objectives, and we learn from those. Our Community Initiatives program gives money to the communities so they can have their own public consultation process and prioritize what they want funded – such as small ski clubs, or dance clubs or other community clubs. Some, like Golden, want funding to build pedestrian bridges and iconic timber-frame bridges to use as a centerpiece for their tourism plan.

The exciting thing is the communities can either fund several small projects, such as pre-school reading programs, a ski club or a basketball program — or they can fund something much larger, like a timber frame bridge project. We give them the flexibility and power to do what they want to do. That’s what is exciting. Environmentally, we’ve funded grassroots stewardship organizations that really want to go beyond talking about environmental stewardship to actively engaging a group of people from schools to the politicians to industry to do something about climate change – maybe a streamside restoration; a leak cleanup; helping folks enjoy their environment; or talking to build relationships with industry on protecting water and plant resources.

We’re funding a land conservation program. One significant characteristic here is our large, intact ecosystems and habitats. But with population growth, they are under threat of being bought, subdivided and sold off. So, in partnership with a number of federal and provincial government agencies, we’re working with NGO’s, local communities, First Nations and industry to purchase large tracts of land and keep a working context in place, so agriculture and forestry keeps going, and that piece of land remains as an integral part of the habitat and ecosystem in this area in perpetuity for future generations so that they can choose what they want to do with it.

And the arts and culture! We fund our wonderful local partner, the Columbia Kootenay Arts and Culture Group and smaller arts and culture councils, so they can utilize that money on the ground. Arts and culture heritage is an important part of the social fabric of every community; and to support that is exciting. They do great work from small community shows, to funding artists, to holding community gatherings that celebrate arts, culture and the environment. They do many projects with a small amount of funding.

NWNL Is use of that funding open ended, or is it specifically for art and cultural projects that relate to the environment?

KINDY GOSAL Our funding is open-ended; and the recipients make their decisions. We tell them to make their own decisions on how to utilize that money. Our goal is to empower and support arts in the basin – and they do a great job with their know-how and passion to do what they do best.

CBT is a wonderful, huge umbrella; but as I said, it’s not perfect. Please don’t leave here thinking everything is perfect.

NWNL But you are closing in on perfection! Thank you for your time, Kindy, and for sharing your observations and your wisdom derived from passion to support the wellbeing of Canadian communities.

Posted by NWNL on November 15, 2023.

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.