Castlegar’s Columbia River Story

Columbia River Basin

|

NEW ESRI StoryMaps: What's On Our Shelves & NWNL Song Library & No Water No Life ESRI |

Columbia River Basin

Walter Volovsek

Resident of Castlegar in Canada’s British Columbia

Alison M. Jones

NWNL Executive Director

Castlegar: Bridges & Sawmills

A Pacific Flyway Site

Hydrodams In British Columbia

Trail Signage

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.

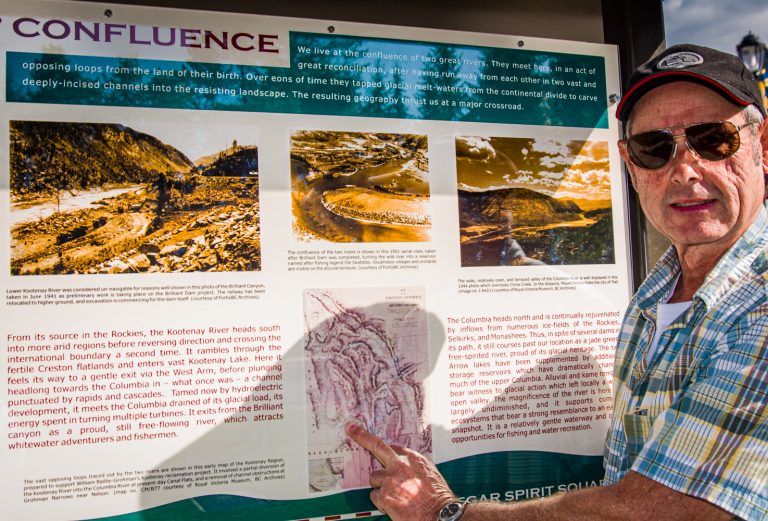

Resident of Castlegar in Canada’s British Columbia, Walter Volovsek is committed to sharing the beauty and history of his town and its river with all who live here or pass through. He explained to NWNL the significant location of Castlegar, at the confluence of the Columbia and Kootenay Rivers. The Columbia comes out of the Upper and Lower Arrow Lakes, making a big bend here towards the south again, having merged with the Kootenay River that runs out of the west arm of the Kootenay Lake.

NWNL Walter, you have worked on signage to highlight the unique values of the Columbia River as it flows through Castlegar. Given that knowledge, what was the inspiration of your dedication to the history and the uniqueness of this corner of the river?

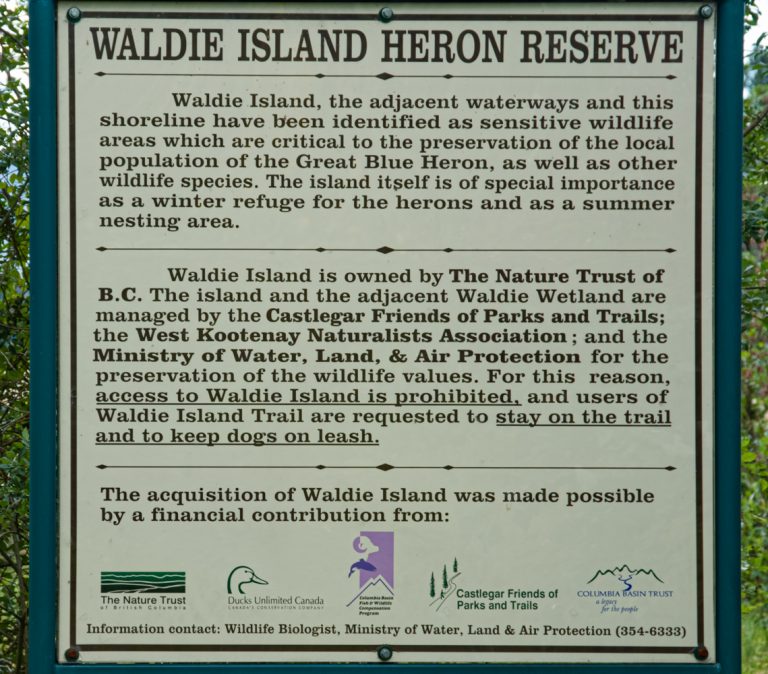

WALTER VOLOVSEK For me, the presence of herons was one clue that I was working with a very unique and important site. I’d previously figured out there were very strong historical values here, as I focused on efforts to preserve a footbridge. That bridge was attached to a railway bridge, upstream from where we are now. The bridge was probably about 70 years old when the Department of Highways wanted to remove it, having completed a new highway bridge upstream.

Some friends and I launched a group to argue for its preservation. My job was to research its history and envision what could be accomplished if the bridge were preserved. I produced a slide show titled “Castlegar Footbridge: A Key to the Past, A Key to the Future.” It was well-received, and most agreed it was influential in preserving the bridge.

I found a replacement for about half a million dollars. I also wrote an article for our brochure, “Whispers in the Wind.” It speaks of walking across the bridge, looking at the river, and hearing imaginary voices from the past. It caught the history of the explorer David Thompson and of annual Canadian fur brigades going up and down the river. It was fascinating to consider all these people coming right past this very spot where we are now. So, I developed an illustrative panel, and then a number of panels, about the historical values of this Columbia River.

The panels speak of the whispers that we can pick up if we give it a little time, because we are on a stretch with the Columbia, its lakes, and the Tincup Rapids just around the bend. Beyond is the confluence with the Kootenay River, another major river. So almost anybody who came through here noticed this confluence in their journals as a major landmark. Thus, I have quotes from these passersby on what they saw during their passage up or down the river.

NWNL I understand there are many unique aspects to Castlegar.

WALTER VOLOVSEK All these journals agree that there is something that makes Castlegar unique in terms of the Columbia River’s setting. Compared to other cities around here, we have a very broad open valley. There’s a lot of room for expansion on the many glacial terraces, and lower down we have some alluvial terraces between ridges and hills where new Castlegar subdivisions are growing

I’m fairly confident that with these opportunities, Castlegar will become the dominant city of this region and be very attractive, because these new growth areas will be broken up by natural landscapes.

NWNL What other changes have you seen here on the Columbia River?

WALTER VOLOVSEK In the 1970s, Castlegar became an amalgamation of two villages: Castlegar at the northern end and the village of Kinnaird to the south.

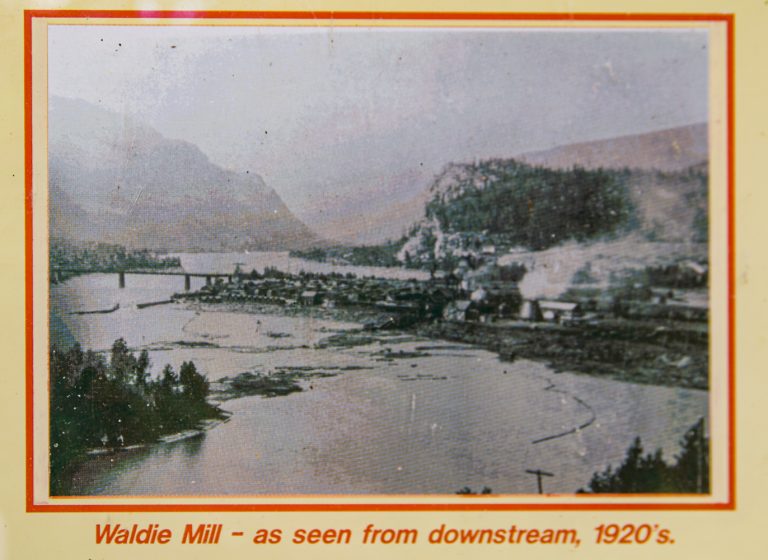

With this amalgamation, new infrastructure had to be developed. Castlegar already had an efficient sewer system based on treatment ponds developed in the 1960s on the site of the old Waldie Sawmill that burned down. The sewer is simply several ponds with some aeration, natural decomposition processes, and some final treatment before the water is released into the river. The ponds are lovely and attract waterfowl. I think they planned it very nicely.

NWNL I’ve heard this free-flowing reach of the Columbia River is part of the Pacific Flyway for migrating birds.

WALTER VOLOVSEK Yes, but it’s probably not as prominent as Creston Valley or the Rocky Mountain Trench, where the more exotic birds can be found. Among the birds that you wouldn’t normally expect here was a yellow-billed cuckoo. When it popped up in this setting in the fall, word went out and people came up from Seattle and all over to see the yellow-billed cuckoo. Sadly, we suspect it perished here, because winter set in very quickly.

NWNL Are there also Western shorebirds that fly along this river?

WALTER VOLOVSEK We’ve seen some American pelicans here and cormorants seem to follow the river up to here from the sea. As well, we have ospreys; and bald eagles are very common. I often see amazing interactions between osprey, bald eagles and herons. Ospreys are very territorial and pick on the herons.

Herons avoid flying near osprey nest sites, such as the railway bridge and stream. They want to avoid being mercilessly dive-bombed and knocked into the water. Their screaming always draws my attention as they attempt to fly away but keep getting dived on. Their only escape is to work their way to the shore and then crawl out and hide under some bushes. It’s amazing to watch this sort of interaction. There’s always something happening here.

NWNL Walter, how did you get to Castlegar and what has kept you busy here?

WALTER VOLOVSEK My parents came to the Castlegar area in the 1960s, because my father was attracted to construction of the Arrow Dam on the Columbia River, later renamed Hugh Keenleyside Dam.. He got a job as a machinist. For a couple of years, I too got a job on the dam, keeping the concrete wet. I wandered all over the site with my camera, creating one of the best records of the evolution of that dam. The dam was an engineering challenge, a technological thing with fancy cranes and heavy-duty equipment.

It was only later, when I became a bit more aware of the price paid by people having to move away, that a dam wasn’t a completely good thing. Dams do carry negative aspects. I remember driving up for a last look at the community of Renata, now-flooded. It was still there, and I couldn’t imagine how it would be when gone, or what it would look like.

About 1968, the flooding started. But in Deer Park, some people refused to move away. They were cut off when the road on to Renata got flooded. One very early fight in this valley was over road reconstruction to return driving access to Deer Park. There were other things and promises about building a creek-side road, a new highway to Needles and a bridge. I still have a brochure on that. The promises fell by the wayside, because under the Provincial Government of Bennett, they took advance payment from America in cash.

This cash was meant to fund the construction of the dams; but costs escalated. All of a sudden, the money was insufficient, and some promised things never happened. What helped in the long run was the founding of the Columbia Basin Trust [CBT] based on money coming back to British Columbia, as part of a downstream-benefits payment by the Americans.

CBT puts good money into our local communities under its mandate to manage and spend this money wisely for varied and worthwhile community functions. CBT also partnered with the Columbia Power Corporation, an offshoot partnered with the Provincial Government. Their mandate is to develop ecologically friendly, almost run-of-the-river dams built on existing structures.

Owned and operated by BC Hydro, Keenleyside Dam never was a generating facility. It wasn’t designed to ever incorporate one. So, Columbia Power Corporation put in a generating facility, called the Arrow Lakes Generating Station with two turbines producing about 167 or so megawatts of power. It has improvements because more water is passed through the generating facility and less is spilled. But it tends to super-saturate the water with nitrogen, which is very negative for the fish downstream. These dams depend on local employment, so they contribute to the local economy. That is a positive thing.

There was talk of building another dam at Murphy Creek. That was one of the earlier BC Hydro concepts and was shelved. I was horrified by that possibility, because it would have personally impacted me. My hope is that Murphy Dam never materializes; but I’m enough of a realist to know that the price of and demand for power will be ever-increasing. If it comes to be, I hope it will be very low-impact and based on low-head turbine technology.

NWNL Walter, I am especially intrigued by your commitment to creating trail development signage. It seems to me a critical element of watershed education.

WALTER VOLOVSEK My work in trail development is strongly focused on developing a sense of local history. I was aware that Castlegar lacked something compared to other nearby, comparable cities. They all have heritage buildings or historic buildings because they had money for government offices and other sturdy buildings. Castlegar was off the beaten track. To compensate, we have other assets here. Certainly, one is the Columbia River, and as well we have a legacy of historic explorers and many others that traveled through Castlegar.

I think this river is definitely our fundamental strength. In discussing our history, I don’t think there was one topic where the river did not play a role. So, I believe the Columbia is key to understanding our history and our future. My work, as I hope to continue it, will be to keep emphasizing the importance of the river in the past, and the importance of preserving a river that still looks and functions like a river into the future. We are blessed to have something like 20 miles of natural river left here. Downstream of here, we’re into Lake Roosevelt, the Grand Coulee Dam’s reservoir.

In this stretch of the Columbia River, Castlegar remains a crossroads, retaining its greatest asset: a free-flowing Columbia River as it rounds the Tincup Rapids and runs on past its confluence here with the Kootenay River.

Posted by NWNL on June 28, 2021

Transcription edited and condensed for clarity by Alison M. Jones.

All images © Alison M. Jones. All rights reserved.